Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts.

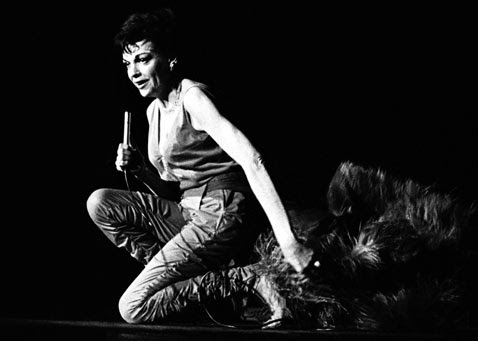

Today we’re commemorating the life and career of Judy Garland, who died 45 years ago this month. Signed to a studio contract at the age of 13, encouraged to become a pill addict as a teenage MGM contract player, crowned a superstar by The Wizard of Oz at age 17 and married for the first time at 18, Garland lived more than her share of life before reaching legal maturity. But today, we’re going to pay particular attention to the last two decades of her life, the post-MGM years, during which Garland battled through one comeback after another, ultimately establishing intimate relationships with her fans on TV and in live performances that would cement Garland’s legacy as one of the most powerful performers of all time. These triumphs were, at the time, usually overlooked by an essentially paternalistic mainstream media which, much to Garland’s dismay, delighted in the negative and the tragic. We’ll explore Garland’s struggles to assert herself within an industry that nearly killed her, and against a media which seemed to be out to get her. We’ll also take a look at Garland’s rise as a gay icon, and the connection between Garland’s death and the Stonewall Riots, which took place the night of Garland’s funeral.

This episode is a little bit different than previous episodes. For one thing, it includes material from interviews with two different experts: Anne Helen Petersen, who writes about Garland in her new book, Scandals of Classic Hollywood, and Peter Mac, a Judy Garland tribute artist whose act features detail-oriented recreations of Garland’s live performances, and who is incredibly well-versed in Garland’s life, work and legacy.

Also, at two different points, I have Friend of You Must Remember ThisNoah Segan reading excerpts from William Goldman’s The Season. The first of these excerpts is an example of the way that Garland often functions as a kind of folk hero, the star of cocktail party anecdotes that become something like tale tales. The other excerpt is more problematic — it’s basically a document of vicious homophobia, although it wouldn’t have been called or recognized as that at the time — and I debated whether or not to include it. Ultimately I decided that I wanted to have it in there because it helped me to remember how significant Stonewall really was, by showing how much it needed to happen, and how much has changed (although of course there’s still a long way to go). This kind of completely casual reporting on “fluttering fags” shows us how different the world that Judy Garland lived in is from the world that began to come into being after her death. There’s some debate as to whether or not there’s a literal, causal relationship between Garland’s death and Stonewall, but there’s no question that the dividing line between the Before Stonewall and After Stonewall eras coincides exactly with the dividing line between Judy Garland’s existence in the world as a living, breathing human being and her post-death existence as a symbol, angel, martyr, whatever. As I’ve tried to show here, I think it’s the emotional connection, the connection in the public imagination, that really matters.

I’ve listed my sources as usual below, but I should also note that my fascination with Judy Garland is longstanding, and though I didn’t pick them up this week, there are a few texts that I’ve basically internalized over the years. One is Ronald Haver’s book on the production, destruction and restoration/reconstruction of A Star is Born. A Star is Born is my favorite film, and Haver’s book is definitely amongst the most impactful books about filmmaking, celebrity, the culture of Hollywood and Hollywood’s ability to create culture, that I’ve ever read. Then there’s an article by Adrienne L. McLean which ran in Film Quarterly in the Spring of 2002, called “Feeling and the Filmed Body: Judy Garland and the Kinesics of Suffering.” This article was the final straw that made me decide to apply to graduate schools, and it’s still a gold standard for me in terms of relating what’s happening in a person’s life off-screen to what they make visible on-screen.

Special thanks to Anne Helen Petersen and Peter Mac for making the time to talk to me. Anne’s book is available for pre-order and will be released in September. If you have an opportunity to see Peter’s show, I highly recommend it. I first saw him perform at The Other Side, a piano bar in the LA neighborhood of Silverlake, which opened in the late 1960s and, sadly, closed in 2012. In that small room, where we would usually sit and drink around the piano, Peter’s note-perfect renditions of songs like “The Man That Got Away” were known to make me cry. He’s headlining a fundraiser for the L. Frank Baum Foundation in Syracuse, New York in August.

————————————

Music in this episode:

“After You’ve Gone” performed by Judy Garland

“Moonlight Saving Me” played by Blossom Dearie

“The Boy Next Door,” played by Blossom Dearie

“I Feel a Song Coming On,” performed by Judy Garland

“Over the Rainbow” performed by Judy Garland

“Come Rain of Come Shine,” performed by Judy Garland

“Preludes for Piano #2,” performed by George Gershwin

“The Man That Got Away,” performed by Judy Garland, from A Star is Born

“The Man That Got Away” instrumental

“Medley: This is The Time of the Evening/While We’re Young,” performed by Judy Garland

“Stormy Weather,” performed by Judy Garland live at Carnegie Hall

“Olv 26” performed by Stereolab

“My Orphaned Son,” performed by DNTEL

“Who Cares,” performed by Judy Garland live at Carnegie Hall

————————————-

Text sources:

Scandals of Classic Hollywood, by Anne Helen Petersen

The Season, by William Goldman

Get Happy, by Gerald Clarke

A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life and Films of Vincente Minnelli, by Mark Griffin

“Judy Garland and Gay Men,” by Richard Dyer. From Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society; also available here.

Jeff Weinstein on Judy Garland and Stonewall (Special thanks to Jeff for making the Obit article available to me when it wasn’t online)

“Did Judy Garland start a riot?” by Andrew Alexander, Creative Loafing

“Does Judy Garland still matter?” by Jesse Green, New York Magazine