Weather on Earth can be wild, but it’s not the only kind of weather we have to deal with. Space weather — all the winds and particles streaming off the sun — can have major impacts on Earth and human infrastructure. In the worst cases, this can mean dangerous disruption to our power grids and communications satellites.

To help us predict these space storms, astronomers have a newly improved space weatherman — and it’s the best one to date. The Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope (DKIST), perched atop the Hawaiian mountain of Haleakalā, is the world’s largest telescope used for studying the sun and predicting these storms.

The team behind this technological marvel recently hit a major milestone, finally turning on one of DKIST’s most powerful cameras — known as the Visible Tunable Filter, or VTF — after more than a decade working on its creation.

This camera is the final piece of the puzzle for DKIST, and the VTF’s addition “will complete its initial arsenal of scientific instruments,” Carrie Black, director of the National Solar Observatory, said in a statement.

“The significance of the technological achievement is such that one could easily argue the VTF is the Inouye Solar Telescope’s heart, and it is finally beating at its forever place,” Matthias Schubert, project scientist for the VTF, said in the statement.

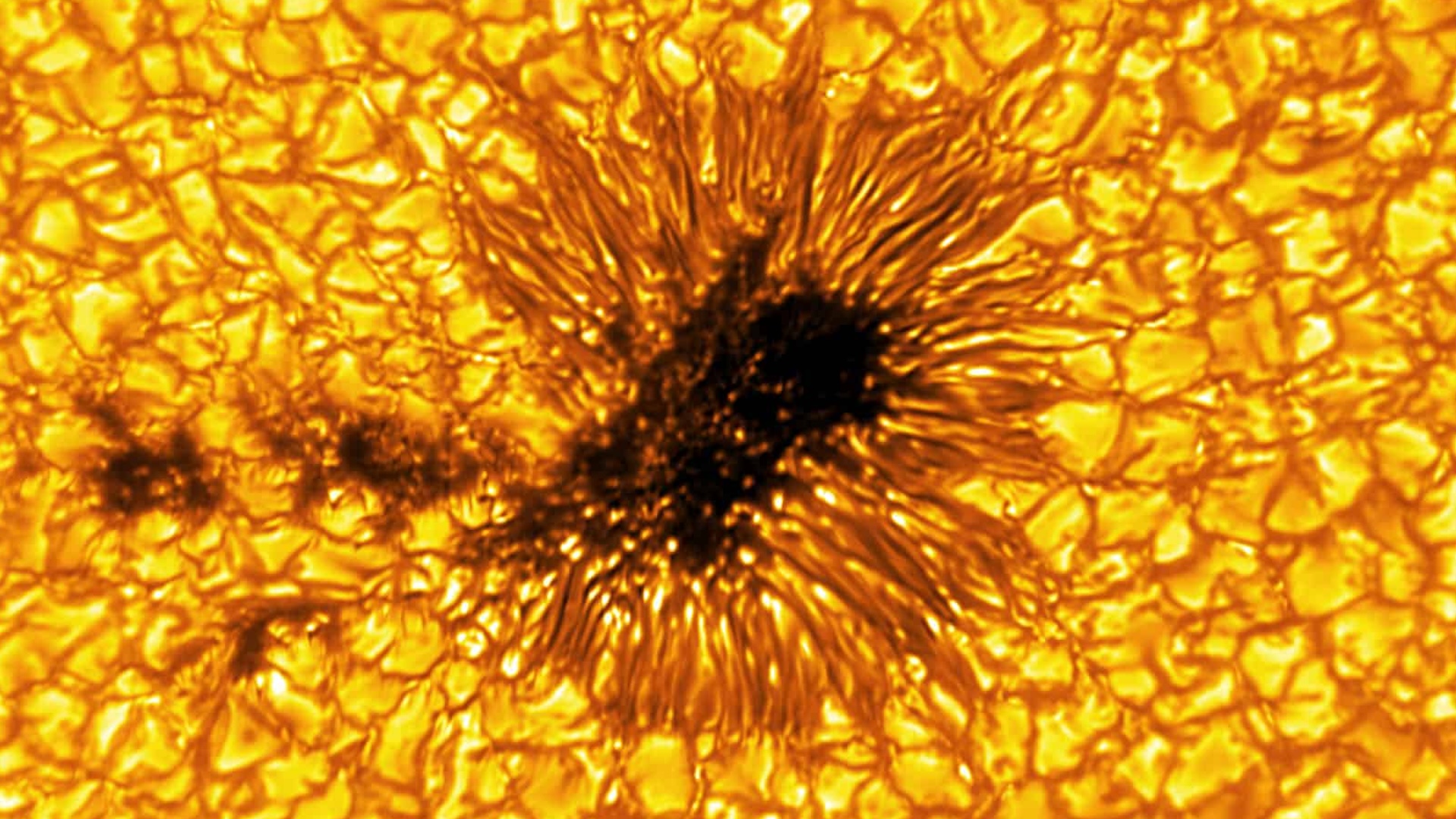

VTF’s first image shows a major clump of sunspots, dark blobs on the sun’s surface caused by its intense magnetic field, each blob measuring wider than the continental United States. This impressive camera can see details down to a resolution of about 6.2 miles (10 kilometers) per pixel on the solar surface — an absolutely wild resolution given that the sun is tens of millions of miles away from us.

Related: A mysterious, 100-year solar cycle may have just restarted — and it could mean decades of dangerous space weather

VTF provides more than just a simple snapshot. It captures images at multiple wavelengths of light to measure a spectrum, while also gathering information on how the light’s electric field is oriented (known as polarization). These extra perspectives on the sun help reveal details of the solar surface, magnetic field and plasma that are otherwise invisible, informing our predictions for space weather and solar flares.

During just one observation of the sun, this instrument can collect more than 10 million spectra — graphs of the light’s intensity over different wavelengths — which help scientists determine how hot the solar atmosphere is, how strong the sun’s magnetic field is and more.

Today’s news is only the beginning for the VTF and DKIST. The incredibly complex instrument still requires more testing and set-up, which is expected to be completed by next year.

But the newly released first images show great promise for how much we can learn about the sun, our nearest star. These images are “something no other instrument in the telescope can achieve in the same way,” said National Solar Observatory optical engineer Stacey Sueoka. “I’m excited to see what’s possible as we complete the system.”