Youth radicalisation and its connection to political violence and terrorism is an urgent concern. Despite consistent warnings from intelligence and law enforcement agencies in Australia and globally, public discussion around this issue often falls short. We need to understand why it persists and how to disrupt it before it escalates.

Australian Security Intelligence Organisation said on 6 December that about 20 percent of its priority counterterrorism cases involved minors. Since 2017, ASIO and the AFP has investigated 35 young Australians for violent extremism, some as young as 12.

Young adults are also a risk factor, as illustrated this month by the apparently ideologically motivated killing of a healthcare CEO in the US. To address their radicalisation, policymakers must grapple with agency: radicalised people are not just vulnerable and manipulated; political violence can be their response to both real and perceived grievances.

A Five Eyes report issued this month highlights disturbing case studies of youth involvement in violent extremism across Australia, Britain, Canada, New Zealand and the United States. These case studies offer valuable insights but focus on social media. While digital environments are important, we risk overshadowing the deeper psychological, societal and cultural factors that underlie youth radicalisation.

We must determine what differentiates those merely exposed to extremist content and those who are radicalised by it. Online interactions may exacerbate radicalisation but are not the sole factor.

Multi-faceted vulnerabilities are part of the answer. For example, individuals who feel alienated, unsupported or marginalised may find a sense of belonging or purpose in extremist ideologies. Understanding complex factors, and their role in the cycle of radicalisation, is necessary to disrupt the cycle.

We must focus on understanding why certain individuals, particularly young people, are drawn to extremist ideologies in the first place. This includes understanding the uncomfortable issue of youth agency in radicalisation.

Agency is absent from the Five Eyes report and much of public discussion. We cannot view radicalised young people only as vulnerable victims. We must consider their conscious participation as an attempt to resolve real or perceived grievances. While agency is tricky to assess in the case of radicalised minors, it is particularly relevant in assessing cases of adult young persons, aged 18 to 25. This demographic is more likely to be politically aware and may be motivated to violent extremism due to a radical ideology or political grievance.

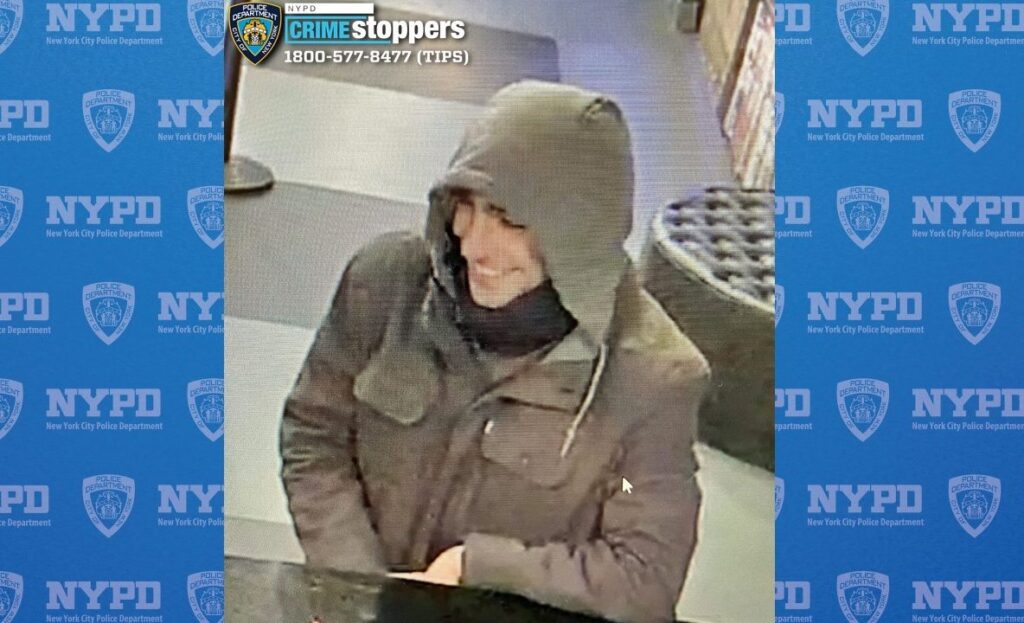

The 4 December killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in New York highlights this issue. The lead suspect, a 26-year-old man, allegedly carried a three-page manifesto criticising corporate America and had engaged with violent extremist literature critiquing wealth inequality. While he was active online, he does not neatly fit the mould of a socially isolated or mentally unwell offender. Nor is it clear whether a specific online group radicalised him.

But the killer’s identity is not the most important issue. After the murder, many young people were quick to understand, even praise, the violence online and vilify the healthcare industry. The lack of universal condemnation of the killing is disturbing—but also reveals political dissatisfaction. Agency is critical to understanding this killing: it was likely motivated by personal and political grievances stemming from social and economic insecurity, either real or perceived, which unfortunately resonate with many young people—including Australians.

Addressing broader causes of youth radicalisation will require a shift in policy. Resolving vulnerabilities will take a whole-of-society strategy that goes beyond the traditional roles of law enforcement and intelligence agencies and engages other sectors, such as education, mental health services and community groups.

Early intervention is key to pre-empting radicalisation. This necessitates better understanding of vulnerabilities that fuel radicalisation, and creation of a supportive environment that offers young people help before they turn to violent ideologies.

Research into the psychological, social and environmental factors that make young people susceptible to extremism is crucial. This research must inform policies and interventions to support and guide at-risk youth. Early interventions, such as mental health support, programs to prevent social isolation and initiatives to foster stronger community connections, can protect against radicalisation. This approach requires a shift in focus from reactive law enforcement to proactive support.

Schools and families must be empowered to play a more proactive role in identifying and supporting at-risk youth. We must show schools and families how to recognise early signs of radicalisation and intervene. This will require identification of specific vulnerability factors and making strategies and support available before issues escalate.

The above solutions will address vulnerabilities. To address agency, the government must also better engage young people, understand their grievances and implement policy in response. Disenfranchised young people contribute to a range of social risk factors, including increased criminality, growth in extremist political movements, and even violent extremism.

We must also continue to recognise the legal distinction between radicalisation and violent extremism. Extremist political views may repel repellent many, but they are legal in democratic societies. We must prevent violence, not free expression, and preserve our democratic values and freedoms.

The government must shift towards a whole-of-society approach addressing vulnerabilities and agency, as well exacerbating factors such as social media, to effectively implement policies to fight youth radicalisation.