Walter Isaacson is the 2014 LEH Humanist of the Year. President and CEO of The Aspen Institute and the best-selling author of biographies of Steve Jobs, Albert Einstein and Ben Franklin, Isaacson contributed this autobiographical article to the new issue of Louisiana Cultural Vistas magazine. To read the full issue online and view more photos from this article, click here. To renew your subscription to LCV, click here. The LEH will honor Isaacson at the March 29th Humanities Awards.

I once was asked to contribute a piece for a section of the Washington Post called “The Writing Life.” This caused me some consternation. A little secret of many nonfiction writers like me—especially those of us who spring from journalism—is that we don’t quite think of ourselves as true writers, at least not of the sort who get called to reflect upon “the writing life.” At the time, my daughter, with all the wisdom and literary certitude that flowed from being a 13-year-old aspiring novelist, pointed out that I was not a “real writer” at all. I was merely, she said, a journalist and biographer.

To that I plead guilty. During one of his Middle East shuttle missions in 1974, Henry Kissinger ruminated, to those on his plane, about such leaders as Anwar Sadat and Golda Meir. “As a professor, I tended to think of history as run by impersonal forces,” he said. “But when you see it in practice, you see the difference personalities make.” I have always been one of those who felt that history was shaped as much by people as by impersonal forces. That’s why I liked being a journalist, and that’s why I became a biographer.

For many years I worked at Time magazine, whose cofounder, Henry Luce, had a simple injunction: tell the history of our time through the people who make it. He almost always put a person (rather than a topic or event) on the cover, a practice I tried to follow when I became editor. I would do so even more religiously if I had it to do over again. When highbrow critics accused Time of practicing personality journalism, Luce replied that Time did not invent the genre, the Bible did. That’s the way we have always conveyed lessons, values, and history: through the tales of people.

In particular, I have been interested in creative people. By creative people I don’t mean those who are merely smart. As a journalist, I discovered that there are a lot of smart people in this world. Indeed, they are a dime a dozen, and often they don’t amount to much. What makes someone special is imagination or creativity, the ability to make a mental leap and see things differently. As Einstein noted, “Imagination is more important than knowledge.”

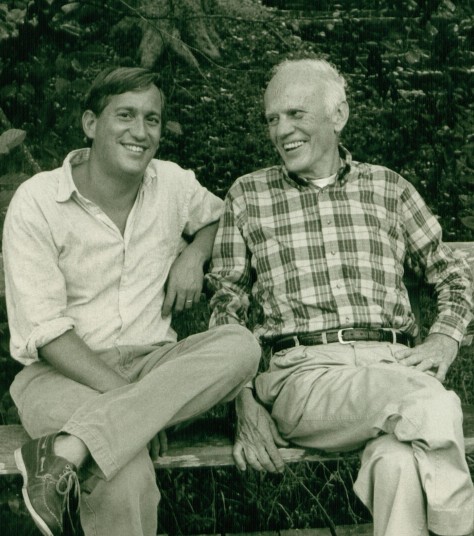

The first real writer I ever met was Walker Percy, the Louisiana novelist whose wry philosophical depth and lightly-worn grace still awe me when I revisit my well-thumbed copies of The Moviegoer and The Last Gentleman. He lived on the Bogue Falaya, a bayou-like, lazy river across Lake Pontchartrain from my hometown of New Orleans. My friend Thomas was his nephew, and thus he became “Uncle Walker” to all of us kids who used to go up there to fish, capture sunning turtles, water ski, and flirt with his daughter Ann. It was not quite clear what Uncle Walker did. He had trained as a doctor, but he never practiced. Instead, he worked at home all day. Ann said he was a writer, but it was not until his first novel, The Moviegoer, had gained recognition that it dawned on me that writing was something you could do for a living, just like being a doctor or a fisherman or an engineer.

He was a kindly gentleman, whose placid face seemed to know despair but whose eyes nevertheless often smiled. I began to spend more time with him, grilling him about what it was like to be a writer and reading the unpublished essays he showed me, while he sipped bourbon and seemed amused by my earnestness. His novels, I eventually noticed, carried philosophical, indeed religious, messages. But when I tried to get him to expound upon them, he would smile and demur. There are, he told me, two types of people who come out of Louisiana: preachers and storytellers. It was better to be a storyteller.

That, too, became one of my guideposts as a writer. I was never cut out to be a pundit or preacher. Although I had many opinions, I was never quite sure I agreed with them all. Just as the Bible shows us the power of conveying lessons through people, it also shows the glory of narrative—chronological storytelling—for that purpose. After all, it’s got one of the best leads ever: “In the beginning,…”

My parents were very literate in that proudly middle-brow and middle-class manner of the Fifties, which meant that they subscribed to Time and Saturday Review, were members of the Book-of-the-Month Club, read books by Mortimer Adler and John Gunther, and purchased a copy of the Encyclopedia Britannica as soon as they thought that my brother and I were old enough to benefit from it. The fact that we lived in the heart of New Orleans added an exotic overlay. Then as now, it had a magical mix of quirky souls, many with artistic talents or at least pretensions. I liked jazz, tried my hand at clarinet, and spent time in the clubs that featured the likes of reedmen George Lewis and Willie Humphrey. After I discovered that one could be a writer for a living, I began frequenting the French Quarter haunts of William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams and sitting at a corner table of the Napoleon House on Decatur Street keeping a journal.

Fortunately, I was rescued from some of these pretensions by journalism. While in high school, I got a summer job at the States-Item, then the feistier afternoon sibling of the Times-Picayune. I was assigned the 5 a.m. beat at police headquarters, and on my first day I found myself covering that most awful of stories, the murder of a young child. When I phoned in my report to the chief of the rewrite desk, Billy Rainey, he started barking questions: What did the parents say the kid was like? Did I ask them for any baby pictures? I was aghast. I explained that they were grieving and that I didn’t want to intrude. Go knock on the door and talk to them, Rainey ordered.

To my surprise, they invited me in. They pulled out photo albums. They told me stories as they wiped their tears. They wanted people to know. They wanted to talk. It’s another basic lesson I learned: The key to journalism is that people like to talk. At one point the mother touched me on the knee and said, “I hope you don’t mind me telling you all this.”

Almost 25 years later, I recalled that moment in the most unlikely circumstance. Woody Allen had been hit by the furor over the revelation that he was dating Soon-Yi Previn, the adopted daughter of his estranged consort Mia Farrow. He invited me to come over to his apartment so that he could explain himself. It was just the two of us, and as soon as I opened my notebook it became clear how much he wanted to talk. At one point, when I asked if he thought there was anything wrong with this set of relationships, he replied in a way destined to get him into the quotation books: “The heart wants what it wants.” After more than an hour, he leaned over and said, “I hope you don’t mind me telling you all this.” I thought to myself, as his psychiatrist might have: No, I don’t mind, this is what I do for a living, I get paid to do it—amazingly enough.

When I went north to Harvard, I drove up with cases of Dixie beer piled in my beat-up Chevy Camaro, so that I could pretend to be a real Southerner, and I reread Absalom, Absalom and The Sound and the Fury, so that I could channel Quentin Compson. The most embarrassing piece I have ever written, which I fear is saying a lot, was a review of a biography of Faulkner for the Harvard Crimson that I attempted to write in Faulkner’s style. Not surprisingly, I was never asked to join the Crimson, but I did join the Lampoon, the humor magazine. Back then the Lampoon specialized in producing parodies, such as one of Cosmopolitan that had a fake foldout of a nude Henry Kissinger. It was thus that I learned, though only moderately well, another lesson that is useful when travelling in the realms of gold: that poking fun of the pretensions of the elite is more edifying than imitating them. I also began, for no particular reason, to gather string and write a chronicle of an obscure plantation owner, then no longer alive, named Weeks Hall, who had, earlier in the century, invited a wide variety of literary figures to be houseguests at his home, which he called Shadows on the Teche. From that I learned the joys of unearthing tales about interesting and creative people.

During the summers, I tended to come back home to New Orleans to work for the newspaper. I liked to think that I had the ability to drive into any small town and, within a day, meet enough new people that I would find a really good story. I pushed myself to practice that every now and then, with mixed success. If I were hiring young journalists now, that would be my test; I would pull out a map, pick out a small town at random, and ask them to go there and send me back a good story in 48 hours.

On one such outing through southern Louisiana, I wrote a set of articles on the life of the sharecroppers on the sugar cane plantations along Bayou Lafourche. The pieces showed the effects of my having read James Agee once too often, but they did help me get an even more interesting job the following summer. Harry Evans, who is now well known as an author and historian, was then the hot, young, crusading editor of the Sunday Times of London. He gave a talk at Harvard in which he lamented that America was no longer producing as many literary journalists in the mold of Agee. Without even a pretense of humility, I put together a packet of my sharecropper pieces and sent them off to him in London, asking for a summer job. I heard nothing, promptly forgot about my impertinent request, and thus was a bit baffled when months later a telegram arrived at my dorm (an occurrence almost as unusual then as it would be today), saying: WILL HIRE FOR LIMITED TERM AS THOMSON SCHOLAR. It was signed by someone I had never heard of, but I soon realized it was an offer from the Sunday Times. The “Thomson Scholar” bit was because Harry needed a way to get around the unions in hiring someone like me, so he made up a fellowship and named it after the paper’s then-owner, Lord Thomson. I scraped up the money to buy a cheap ticket on Icelandic Air to London.

It was the summer of 1973, and the Watergate scandal was unfolding. Harry created an investigative unit, known as the Insight Team, and put me on it, under the mistaken impression that, since I was an American, I bore some resemblance to Woodward and Bernstein. My first big assignment was to go up to Dundee, Scotland, where the mayor, quaintly known as the Lord Provost, was suspected of having Nixonian tendencies. When I arrived at the airport, I cockily presented my Sunday Times press credential at the car counter only to be told that I was not old enough to rent one. Too embarrassed to tell my editors, I hitchhiked to my hotel.

Over the next few days, I was able to meet a lot of local characters and get them to talk. I pieced together a tangled web involving secret land purchases combined with nefarious adjustments to zoning laws and perhaps even a connection to a mysterious murder. The article I wrote so baffled and unnerved my editors that they sent in reinforcements in the person of the most amazing journalist I have ever known, David Blundy. He was wild-eyed, boisterous, thrill-seeking, conspiratorial, and so excessively lanky that he looked like an animated cartoon character. One night when we returned to the hotel, the desk clerk mentioned that someone was in our room. David uncoiled himself into full alert mode, assuming that it must be some thug hired by the Lord Provost, and barked to me that I should take the elevator and he would take the stairs. The point of this eluded me, but I did as I was told. We arrived at the sixth floor at the same time. David flung open our door and, since he was a chain smoker, immediately collapsed on the floor wheezing from his race up six flights of stairs. The interloper turned out to be a television repairman who scurried out of the room leaving various parts strewn on our floor.

I subsequently partnered with David on stories involving the troubles in Northern Ireland, Morocco’s war for the Spanish Sahara, and a ring of traders violating the sanctions against Rhodesia. He was exhilarated by danger. Once in Belfast he insisted that we go cover a demonstration, when I was quite content to stay at the bar of the Europa Hotel. He showed me that even though the street clashes might seem violent and bloody on television, just a half block away things were calm and safe. Journalism required an eagerness to get up and go places. While we were out, a bomb went off at the Europa Hotel. Blundy insisted that this should serve as a lesson for me. I agreed. But when he got killed a few years later by a sniper’s bullet in El Salvador, I gave up trying to fathom the meaning of the lesson he wanted me to learn.

At the Sunday Times, I learned that I was not cut out to be a Woodward or Bernstein. I tended to like people too much to relish investigating them. Perhaps that’s the flip side of finding it easy to meet strangers and get them to talk. For example, one week I was sent to cover a fire at an amusement center, known as Summerland, on the Isle of Man, in which 50 people had died because of chained exit doors and other lapses. I ended up meeting Sir Charles Forte, the chief executive of the company that owned the park. He was very open, indeed vulnerable, as he discussed the mistakes that had led to the tragedy. It made for a good story, but it could have made for a really great story if I hadn’t decided to downplay some of what he told me. My instinct to be sympathetic got the better of my instincts as a journalist.

This tug exists both for journalists and biographers. Some are good at getting access, others are better at being tough investigators. Before Watergate, some of the most prominent journalists—Walter Lippmann, James Reston, Joseph Kraft, Hugh Sidey—made their name because they had access to powerful people and seldom played gotcha when conveying their thoughts. Today such softness and coziness is generally disparaged. Journalism is, for the most part, better because of that. The glory now goes to investigative journalists who are challenging, probing, skeptical, and tough.

I learned from Harry Evans’s example that it was possible to be crusading and investigative while also retaining access to the people you cover. With his engaging manner and skeptical curiosity, he could be both an outsider (he was from Manchester) and an insider (he was knighted), as the occasion warranted. Every now and then, this lesson would be reinforced for me. For example, my first week covering the 1980 presidential campaign of Ronald Reagan for Time, I wrote a piece that looked at the facts he used in his stump speech, ranging from taxation levels to how trees caused pollution, and declared many to be dubious. I thought I would be shunned by the campaign staff on the plane the following week. Instead, I was invited to the front to ride with the candidate. There’s a phenomenon common to many people in public life. Bill Clinton’s mother described it when she said that if he walked into a room of 100 people, 99 of whom loved him and one who was a critic, he’d head over to that one to try to convert him. I found that true of Henry Kissinger, as well. Like a moth to flame, he is attracted to his critics and feels compelled to convert them.

My stint at the Sunday Times helped me win a Rhodes Scholarship, in part because members of Rhodes selection committees tend to be, not surprisingly, quite Anglophilic. My panel was thus probably overly impressed by bylines in a British newspaper. The interviews took place in a French Quarter hotel, and I was spending my Christmas break shucking at a nearby oyster bar where, fortunately, nobody had any idea what a Rhodes Scholarship was. Since my dream at the time was still to be a “real writer,” I was quite intimidated when I saw that Willie Morris was on my selection panel. I paid no heed to one of the other judges, an Arkansas law professor who was about to launch an unsuccessful campaign for Congress. Years later, Bill Clinton surprised me by recalling the questions he had asked and the answers I had given. He also told George Stephanopoulos that I would go out of my way be tougher on him as a journalist now that I realized he had been on my selection committee. He knew that the remark would get back to me, and he probably calculated it as a bit of reverse psychology.

At Oxford I studied philosophy, politics, and economics; combined with my history and literature concentration at Harvard, that prepared me to be a journalist and biographer, but not much else. My adviser there was a lively but wise professor named Zbigniew Pelczynski, a Hegel scholar who had been active in the Polish Underground during World War II. Once again, I was exposed to the specter of Bill Clinton. Pelczynski assigned me a paper on how democratic undercurrents can be manifest in authoritarian regimes, which I promptly dashed off. He was not impressed. There was a better paper that had been written by a star student of his a few years earlier, and he made a copy of it for me. I probably knew the author, he said. No, I said glancing at the name. But he’s from Arkansas and you’re from Louisiana, Pelczynski pointed out. I allowed that not everyone in Louisiana knew everyone in Arkansas; indeed, I suspect I let my petulance show by declaring that I’d never known anyone at all from Arkansas, ever. Bill Clinton’s paper, on democracy in Russia, was in fact far better than mine, which made this unknown professor’s pet from Arkansas seem all the more annoying.

Under Pelczynski’s spell, I considered becoming a philosopher. Well, not really a beard-stroking philosopher, but at least pursuing an academic career in the field. I had written my Oxford dissertation on an aspect of John Locke’s view of property, and I decided to send it to two philosophy professors I’d had at Harvard: John Rawls and Robert Nozick. This was an inspired approach, since they held opposing views on Locke’s notion of property, so one of them would likely find my analysis interesting. On my way home after finishing Oxford, I went to call upon each to see which might want to take me under wing as a doctoral candidate. Both of them, Rawls somewhat more politely than Nozick, let me know, based on reading my Oxford dissertation, that they had concluded that the world of philosophy could make do quite well without my services. Thus I went back to the New Orleans States-Item, which was then in the process of being absorbed into the Times-Picayune.

I was assigned to cover City Hall, a job made easier because Mayor Moon Landrieu, who was dedicated to integrating the power structure of the city, hired Donna Brazile to be an assistant and the guardian of his door. Most of the old politicos resented having a young, black woman controlling their access to the mayor. But I found her sassy attitude refreshing, and I used to pump her for gossip and information. A key to journalism is spotting people like Donna, who are always completely clued in. Star reporters like Woodward and Bernstein never reveal their sources. I subscribe to a 30-year statute of limitations. Donna gave me some of my best stories.

While I was working at the States-Item, an editor at Time was dispatched to venture forth from Manhattan and find young journalists from “out there.” New Orleans had just held a mayoral primary featuring 12 candidates, each quirky in a delightfully different way (one of them was married to the founder of Ruth’s Chris Steak House and campaigned wearing a gorilla suit on the platform of buying a gorilla for the Audubon Park zoo). I had gone around to every ward leader and made them fill out a chart of how many votes each candidate would get in that ward. With that and a bit of luck, I was able to predict correctly the order and vote percentages. When the Time editor arrived in town, the paper was touting my feat in its promotional ads. He offered me a job, which I accepted. My last act at the newspaper was to write a column predicting the result of the runoff. I got it wrong.

I was the only reporter from “out there” who had been found by this wandering editor, and when I arrived at the Time-Life Building I was brought like a proud catch to the 34th floor to be presented to the top boss, Hedley Donovan. Donovan proclaimed how pleased he was that they had found someone from “out there,” because far too many of the people at the magazine had gone to Harvard and Oxford. By the way, he asked, where did I go to school? I thought he was joking, so I just laughed. He repeated the question. The editor who had found me gave me a nervous look. I mumbled Harvard in a drawl that I hoped made it sound like Auburn. Donovan looked puzzled. I was whisked away. I do not recall ever being brought to meet him again.

As I settled into the New York and Washington media worlds, I noticed that Donovan, who himself had gone to Oxford, had been onto something: The national media establishment was quite insular. Its members (including eventually myself) were more likely to be found at a Council on Foreign Relations meeting than at a Rotary Club lunch. So when I became editor of Time, I organized a three-week Greyhound bus trip across America, on old U.S. Highway 50, which forms the Main Street of scores of towns across the nation’s midsection. We dropped in at chicken-processing plants and bowling alleys, Kiwanis Clubs and PTA meetings, Pentecostal churches and cheap bars that cashed checks on payday. Some of the young writers on the trip had never shopped at a Wal-Mart and didn’t know you could buy guns there, needed encouragement before they would talk to a stranger in a bar or diner, and had never seen first-hand that there were very normal people who harbored resentment about such issues as immigration.

While working at Time, I also discovered that writing biographies and histories could be a satisfying accompaniment to a day job in journalism. When covering the 1980 Reagan campaign, I was struck by the bug-eyed bevy of people who showed up on the fringes of rallies and handed out leaflets purporting to expose the insidious nature of the east coast foreign policy establishment. The leaflets were filled with charts and arrows about the Trilateral Commission, Council on Foreign Relations, Rockefellers, Bilderberg Group, Skull and Bones, and various banking cabals. I asked my Time colleague Evan Thomas about it, under the theory that as an east coast preppie he could decode it all. Eventually we began to talk about writing a book that would explore the reality and myths about “the Establishment.”

We sketched it out in a summer cottage in Sag Harbor on Long Island. I’m a night person, and would try to stay up until 5 a.m., at which point I would hand over my notes to Evan, who got up around then. We’d go to the beach in the afternoon. We came around to the dual approaches that were at the core of our work at Time: Tell the tale through people, and make it a chronological narrative. We selected six men who were at the core of the so-called Establishment (Dean Acheson, Averell Harriman, Robert Lovett, John McCloy, Chip Bohlen, and George Kennan), and we traced chronologically their intertwined lives through prep school, college clubs, Wall Street, the foreign service, Cold War statecraft, and the Vietnam War.

We took our outline down the street in Sag Harbor to Amanda Urban, who had recently become a literary agent, and she sent us further down the street to Alice Mayhew, who was an editor at Simon & Schuster. She heard us out for a few minutes, grasped the idea immediately, and said that she had always wanted to publish such a book and it should be titled, The Wise Men. And so it was.

We were concerned that academics would dismiss our book as being too (or “merely”) journalistic, so we immersed ourselves in presidential archives and relied heavily on what real historians reverentially call “the documents.” That proved useful after one of our early interviews, in which McGeorge Bundy denigrated our thesis that there was anything that could be called an “establishment” group guiding foreign policy. Then Evan found, in the Lyndon Johnson archives, a memo by Bundy titled “Backing from The Establishment,” which detailed the behind-the-scenes role our characters played and urged Johnson to create an advisory group of them that would offer support for the Vietnam War.

But I also became convinced of the benefits of journalistic legwork, not just archival research, in writing contemporary history. For example, the daily letters that Lovett wrote Harriman provided a wealth of archival documentation, but by the late 1950s, when long-distance telephoning became common, they were abruptly replaced in the files by cryptic phone messages saying such things as “call me regarding Laos.” It thus helped to be able to interview the players with a reporter’s notebook in hand.

That was all the more the case when I set out to write a biography of Henry Kissinger. I learned that many of the documents in the archives had been written more for the purpose of posterior-covering rather than historical accuracy. (Winston Lord told me that Kissinger sometimes had him write three versions of meeting memos: one for the archives, another for Nixon, and an accurate one for Kissinger.) So it helped to go out and ask the players what truly lay behind the official memos. As Kissinger himself once pointed out: “What is written in diplomatic documents never bears much relation to reality. I could never have written my Metternich dissertation based on documents if I had known what I know now.”

Kissinger, it turned out, was not excessively thrilled by what I wrote, and he let me know. Over a two-day period, as he read the just-published book, he dictated a flurry of letters declaring various points I made to be “outrageous.” Some were hand-delivered from his office on Park Avenue to the Time-Life Building by a mildly amused L. Paul “Jerry” Bremer, who was then Kissinger’s young associate and later had the slightly easier job of being America’s viceroy in Iraq. At one point Kissinger confronted his close friend, Henry Grunwald, who was Editor in Chief of Time Inc., and thus my boss. Grunwald told Kissinger that he considered my book to be fair and straight down the middle. Kissinger paused and then grumbled, with that ironic sense of humor that saved him, sometimes, from pomposity, “And what right does that young man have to be fair and straight down the middle about me?”

Perhaps as a reaction, I decided to do my next book on someone who had been dead for 200 years. I picked Benjamin Franklin because I felt the country was becoming too ideologically and politically polarized. Franklin was the founder who helped the others find common ground and practical solutions. He realized that tolerance and compromise would be the new nation’s key civic virtues. These were ideals I felt could use a little exalting at the time. Instead of doing it by preaching, I again felt it was better to convey these ideals through narrative biographical storytelling.

One of the things that struck me about Franklin was that he was an avid and serious scientist. We sometimes think of him as a doddering old dude flying a kite in the rain, but his experiments produced the most important scientific advance of the era, the single-fluid theory of electricity, and the most useful invention, the lightning rod. Whether he was charting the Gulf Stream or recording botanical designs, he loved science and would have considered as philistines those who took no interest in it. In our age, however, many supposedly educated people feel comfortable joking about how they are clueless about science and intimidated by math. They would never admit to not knowing the difference between Hamlet and Macbeth, but they happily concede that they don’t know the difference between a gene and a chromosome or between the uncertainty principle and relativity theory. I wanted to show that science—even for a non-scientist like myself—could be fascinating and creative and imaginative. Once again, the best way to convey that message was through the narrative of a person, in this case Albert Einstein.

“All biography is autobiography,” Emerson says, and I suspect I have projected some of my own sentiments on the subjects I profile. That is particularly true of Franklin. A successful publisher, journalist, and marketer—and a consummate networker with a techie curiosity—he would have felt right at home in the information revolution and as a striver in an upwardly-mobile meritocracy. I could relate to that. My daughter once pointed out the obvious, that in writing about Franklin I was writing about an idealized version of myself. Yes, I admitted, but what about Einstein? That, she noted, was me writing about my father. Indeed, my father is a kindly, Jewish, distracted, humanistic engineer with a reverence for science. Einstein was his hero, just as my father has been mine. At that point I asked my daughter what she thought I was doing when I wrote about Kissinger. “That’s easy,” she said, “You were writing about your dark side.”

One topic that has always interested me, is the impact of technology on our lives. In 1989, I went to Eastern Europe to cover the unraveling of the Soviet communist empire. When I got to Bratislava, in what was then Czechoslovakia, I was put in a hotel where foreigners stayed, one of the few places with satellite television. One of the maids asked if I minded my room being used in the afternoon by school kids, who liked to watch MTV and the other music video channels. I said sure, and I made a point of coming back early so that I could meet the students. But when I came in, they weren’t watching MTV. They were watching CNN, which was showing the unrest at the Gdansk shipyard. I realized that the collapse of authoritarian regimes was inevitable because they would eventually be unable to control the free flow of information in a digital age.

Ten years later in Kashgar, a village in western China across the Gobi desert from the rest of the nation, I had a similar experience. In the back of a small coffee shop on an unpaved street, three kids were sitting around a computer. I asked what they were doing. They were on the Internet, they said. I asked to try something and typed in “time.com.” The screen said, “Access denied.” I typed in “cnn.com.” Again, access denied. One of the kids elbowed me aside and typed in something. CNN popped up. He typed something else. Time popped up. I asked what he had done. “Oh,” he said, “we know how to go through proxy servers in Hong Kong that the censors are clueless about.” As I watch that region of western China erupt in occasional protests coordinated on Twitter and Facebook, and as I see the same happening in Iran and elsewhere, I realize that digital technology will do more to shape our politics than anything since Gutenberg’s introduction of the printing press to Europe help usher in the Reformation.

In the early 1990s, even before the advent of the World Wide Web, I was struck by the rise of online communities such as the Well. We did a cover called “Welcome to Cyberspace,” and it was clear that we were seeing a fundamental transformation of media. Up until then, information tended to be packaged by large companies and handed down to a mass audience. Henceforth, there would also be another model: Communities would be built online in which participants created and shared information among themselves, peer to peer. When I was put in charge of “new media” for Time Inc., our group focused on creating communities and discussion groups online, rather than merely using the net for cheap electronic distribution of our magazines. Time and its sister publications struck partnerships with CompuServe, Prodigy, and the fledgling AOL to create and moderate a variety of online bulletin boards and discussions about our articles.

The Web changed things. We were no longer confined to the walled gardens carved out of the Internet by the commercial online services. It became easy—almost compelling—to put our entire magazine online along with all sorts of pictures and added features. The idea of community got downgraded to a few “comments” sections at the bottom of pages. Users were no longer treated as members of our community; instead, they were surfers who glided by while glancing at our articles.

At first we though that users might pay for such privileges, but once we helped develop the idea of banner ads, young account executives from Madison Avenue came rushing to our door with bags of money to pay for as many user eyeballs as we could muster. So we also got seduced by Stewart Brand’s mantra that “information wants to be free, because it is now so easy to copy and distribute,” while ignoring the second part of his formulation, which is that “information wants to be expensive, because in an Information Age, nothing is so valuable as the right information at the right time.” There is a tension between the two parts of his concept, one that we still must resolve.

The new technology offers wonderful possibilities for the so-called writing life. I hope, for example, that my next book will be written with an electronic reading device, such as a Kindle or Sony Reader, in mind; I want to integrate my words with music and pictures and voices. I think journalism can thrive in the digital realm as well. It will be deeply enriched by citizen journalists and bloggers, while traditional journalists will benefit from magical new ways to distribute what they produce. Even old-fashioned print may benefit. Paper, after all, is a very good technology for the storage, retrieval, distribution, and human browsing of information. It could find an enduring niche as a convenient complement to electronic forms of information distribution.

For this new utopia to rise, however, we will have to answer a pressing question: How will writers (or anyone else who creates anything that can be digitized, from movies to music to apps to journalism) make a living in an era in which digital content can be freely replicated? That is now my greatest worry as I contemplate the so-called writing life that I hope to continue—and that I hope my daughter and all future generations will continue.

For 300 years, ever since the Statute of Anne was established in Britain, there has been a system under which people who created things, such as books or articles or music or pictures, had a right to benefit from the making and distribution of copies. Because of this copyright system, we have encouraged and rewarded three centuries of creativity in all sorts of fields of endeavor, and this has produced a flourishing economy based on the creation by talented individuals of intellectual property. Among other things, this allowed all sorts of people, ranging from Walker Percy on down to me, to make a living at the so-called writing life. May the next generation enjoy that delightful opportunity as well.

__________________________________________

Walter Isaacson is an American writer and biographer. He is the President and CEO of the Aspen Institute, a nonpartisan educational and policy studies organization based in Washington, D.C. He has been the Chairman and CEO of CNN and the Managing Editor of Time. This essay was excerpted from his book American Sketches: Great Leaders, Creative Thinkers, and Heroes of a Hurricane, published in 2009 by Simon & Schuster. In May he will deliver the 2014 Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities, the most prestigious honor the federal government bestows for distinguished intellectual achievement in the Humanities.