A groundbreaking study on the skeletal remains from the 16th-century English warship Mary Rose suggests that a person’s dominant hand could influence changes in collarbone chemistry as they age. The research, led by Dr. Sheona Shankland of Lancaster University, sheds light on the unique relationship between handedness and bone composition.

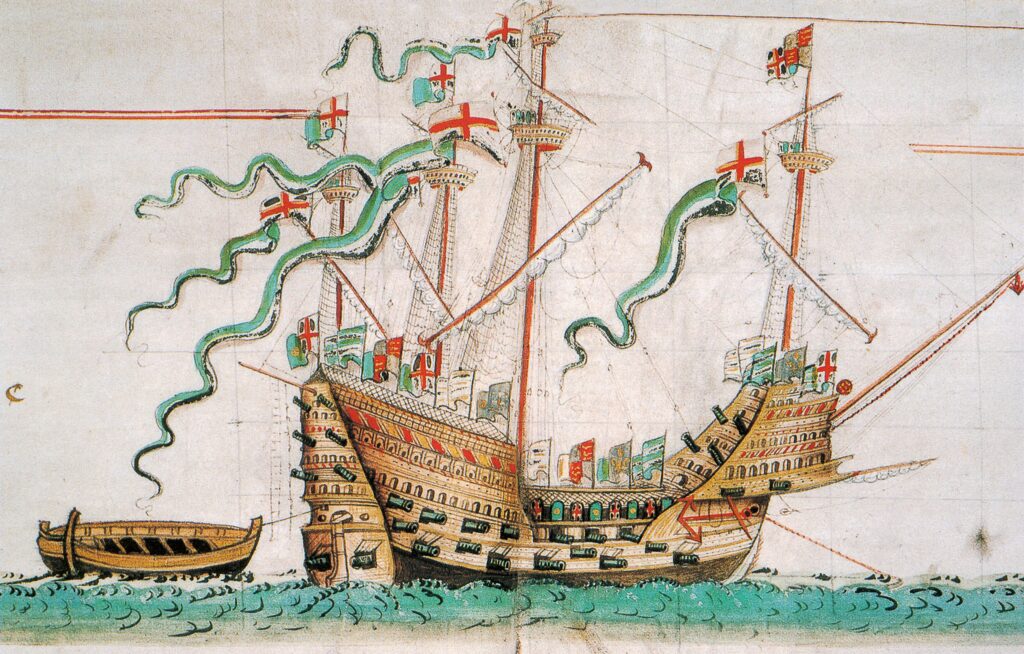

The Mary Rose, a prized vessel in Henry VIII’s Tudor navy, met a tragic fate on July 19, 1545, sinking during the Battle of the Solent while engaged in a fierce conflict with French forces. Preserved under the sea for centuries, the ship’s artefacts and the skeletal remains of its crew have provided a rare glimpse into the past, allowing researchers to piece together the lives and health of these 16th-century sailors.

“Having grown up fascinated by the Mary Rose, it has been amazing to have the opportunity to work with these remains,” says Dr. Shankland. “The preservation of the bones and the non-destructive nature of the technique allows us to learn more about the lives of these sailors, but also furthers our understanding of the human skeleton, relevant to the modern world.”

Dr. Shankland and her team examined clavicle bones from twelve men, aged 13 to 40, who went down with the ship. Using a non-destructive method called Raman spectroscopy, they analyzed the bones’ chemical makeup, focusing on how physical activity and aging may leave their mark. This analysis revealed differences in the clavicle’s mineral and protein content, with a pattern of increasing mineralization and slight protein reduction as age advanced.

Interestingly, these age-related chemical changes were more pronounced in right clavicles than in left ones. Given that right-handedness was the societal norm and that left-handedness was even stigmatized during the Tudor period, the findings suggest that frequent use of the right arm may have led to greater wear and chemical adaptation in the right clavicle.

“It has been a privilege to work with these unique and precious human remains to learn more about life for sailors in the 16th century,” Dr. Jemma Kerns remarks. “Finding out more about changes to bone composition as we age, which is relevant to today’s health, has been fascinating.”

The researchers highlight the potential of such studies to deepen our understanding of how lifestyle factors like handedness can shape bone chemistry over time. Prof. Adam Taylor also emphasizes the significance of the findings: “This study sheds new light on what we know about the clavicle and its mineralization. The bone plays a critical role in attaching your upper limb to the body and is one of the most commonly fractured bones.”

Dr. Alex Hildred of the Mary Rose Museum reflects on the importance of this research in understanding the lives of the sailors and the legacy they left behind. “Our museum is dedicated to the men who lost their lives defending their country. The hull is surrounded on three sides by galleries containing their possessions, and we continue to explore their lives through active research. The non-destructive nature of Raman spectroscopy makes it an ideal research tool for investigating human remains,” he explains. “We are delighted that the current research undertaken by Lancaster Medical School not only provides us with more information about the lives of our crew, but also demonstrates the versatility of Raman. The fact that this research has tangible benefits today, nearly 500 years after the ship sank, is both remarkable and humbling.”

This study opens new avenues for understanding how the body adapts to repeated physical stresses and the role that handedness might play in bone health, potentially impacting modern fields like orthopaedics and forensic science.

The article, “Shining light on the Mary Rose: Identifying chemical differences in human aging and handedness in the clavicles of sailors using Raman spectroscopy,” by Sheona Isobel Shankland, Alexzandra Hildred, Adam Michael Taylor and Jemma Gillian Kerns, is published in PLOS ONE. Click here to read it.

Subscribe to Medievalverse