“See what a lot of land these fellows hold, of which Vicksburg is the key! The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket.”

— Abraham Lincoln

“ … the nailhead that holds the South’s two halves together.”

– Jefferson Davis

The vital importance of controlling the Mississippi River was apparent from the beginning of the Civil War. The river not only served as a crucial supply route but also facilitated the transportation of troops and military provisions, while also aiding in effective communication. By gaining control over the Mississippi River, the Union would effectively cut off the Confederacy’s access to this vital thoroughfare, creating a division between the western and eastern southern states. Furthermore, this strategic move would enable Northern traffic to freely navigate the entire length of the river, essentially transforming it into a logistical superhighway that would greatly influence operations in the Western theater.

By June 1862, the Union army and naval forces had captured New Orleans and many other forts and cities along the Mississippi River. However, the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg in Mississippi remained under their control. With General Halleck’s transfer to Washington as the commander-in-chief, General Grant assumed command of the Army of Tennessee and was entrusted with capturing Vicksburg. This was no easy task. It had been tried by others without success.

Admiral Farragut had attempted an assault up the river in May 1862 after he captured New Orleans. He demanded surrender but he had insufficient troops to attack. Returning with a flotilla in June 1862, his attempts to bombard the fortress into surrender were unsuccessful. Throughout July, the Navy shelled Vicksburg and engaged in minor battles with Confederate vessels in the area, yet their forces were not enough to attempt a landing, leading to the abandonment of the mission.

Geography

Vicksburg held immense strategic significance due to its geographical location overlooking a sharp 180-degree bend on the Mississippi River, situated atop a towering 200-foot bluff. Because of the horseshoe turn, ships were essentially forced to face toward it, then away from it, and had to maneuver slowly. Perched on high, steep bluffs 200 feet above the river and heavily defended by forts and earthworks, it was heavily defended with formidable forts and earthworks. It was called the “Gibraltar of the Confederacy” for good reason, as it appeared impregnable to any military force of that era.

North and east of Vicksburg, the Mississippi Delta was formed by the convergence of the Yazoo River with the Mississippi River. Spanning over 7000 square miles, this alluvial floodplain boasts an intricate network of streams, rivers, bayous, and swamps. Some of these waterways were navigable, while others were impassable. The Delta is a 7000 square mile alluvial floodplain, with many streams, rivers, bayous, and swamps, some of which were navigable, some of which were entirely unpassable. Its geological origin is that of regular flooding of both rivers over thousands of years, creating a flat, fertile land with swamps and other wetlands. It was a land inhabited by swarms of mosquitoes carrying malaria, poor roads, and untamed wilderness. Additionally, it housed some of the largest, most productive, and isolated cotton plantations. The slave population in this area developed its own unique culture and music, which eventually emerge as Mississippi Delta Blues.

A bayou is a sluggish and narrow river characterized by an ill-defined shoreline, often associated with a marshy lake or wetland. It can also refer to a creek whose direction of flow changes daily due to tidal shifts. Bayous typically contain brackish water and are frequently boggy or stagnant. On the other hand, a swamp or marsh is a low-lying wetland predominantly covered by woody vegetation. These areas experience saturation of water in the ground and are either partially or intermittently submerged. Swamps and marshes serve as transitional zones between land and water. Wetlands encompass not only floodplains but also other areas that are prone to flooding or remain underwater.

The Initial Advance

Ulysses S Grant assumed command of the Army of Tennessee and immediately devised a strategic plan. Departing from Memphis, he aimed to trace the path of the Mississippi Central Railroad towards the south, reaching Holly Springs. Meanwhile, General Sherman was entrusted with leading four divisions, totaling around 32,000 soldiers, down the river. Grant, on the other hand, would continue his advance with the remaining forces, approximately 40,000 strong, along the railroad line towards Oxford. The Confederate forces, under the leadership of Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton, posed a formidable challenge, with 12,000 troops stationed in Vicksburg and Jackson, Mississippi, while Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn commanded around 24,000 soldiers in Grenada.

Grant faced numerous obstacles in his mission, including the Confederate Army’s opposition, the demanding terrain and geographical features, the prevalence of diseases, and logistical difficulties in maintaining a steady supply chain. However, his most significant concern came from the political realm. President Lincoln envisioned a two-pronged offensive strategy, with Major General John McClernand authorized to advance down the river, while Nathaniel Banks would move upstream from New Orleans. This political pressure added an additional layer of complexity to Grant’s already challenging circumstances.

General Grant’s initial strategy to reach Vicksburg by taking the most straightforward overland route, following the train road, proved to be unsuccessful. The problem with this direct approach was that it was too predictable and vulnerable: any threat to the single-lane Mississippi Central Railroad would have disastrous consequences. Unfortunately for Grant, the Confederates had Nathan Bedford Forrest, a skilled commander who posed a significant threat to this route. As a result, Grant’s offensive failed as raids by Van Dorn and Forrest disrupted his supply lines and communication networks. The destruction of the supply depot at Holly Springs forced Grant to abandon his original plan.

Chickasaw Bayou

Meanwhile, Sherman moved downriver to Johnson’s Plantation and attempted a direct northeast advance toward Vicksburg. However, this strategy required traversing through swamps and facing strong defenses on hills overlooking a bayou. Despite launching attacks for three consecutive days at Chickasaw Bayou (December 26 – 29, 1862), Sherman’s forces made no progress. The heavily fortified hills and the challenging terrain hindered their advancement, leaving them unable to break through.

On December 27, the Union army pushed their lines forward through the swamps toward the Walnut Hills, which were strongly defended. On December 28, several futile attempts were made to get around these defenses. On December 29, Sherman ordered a frontal assault, which was repulsed with heavy casualties, and then withdrew.

The problem was that the bayou ended in a wall of hills, the Walnut Hills, which provided a strong defensive advantage. The strategic significance of this attack was in its proximity to Vicksburg, which is exactly what enabled Pemberton to bring sufficient manpower for its defense. Another factor was that Porter’s bombardment failed to have an important effect. Sherman had over 30,000 men of whom 1700 were casualties; Pemberton had about 14,000 with less than 200 casualties.

General McClernand and Arkansas Post

Meanwhile, General McClernand led his Corps to Memphis and proceeded down the Mississippi River, where he instructed Sherman to join forces with him, disregarding Grant’s directives. Their target was Arkansas Post, home to Fort Hindman at the junction of the Arkansas River, located 50 miles upstream. With the support of Admiral Porter’s ironclads bombarding the fort, they managed to land sufficient numbers of troops to capture the fort and take prisoners despite sustaining heavy losses.

Initially skeptical of the expedition, Grant expressed disapproval in a letter to Halleck. However, the successful outcome compelled Grant to recognize its importance and collaborate with McClernand. The capture of Fort Hindman was crucial in preventing potential threats from the rear, underscoring the necessity of neutralizing such strongholds to secure Grant’s position.

Although McClernand incurred over 1000 casualties in a 30,000-man army, he captured 5000 Confederates. Grant would need to win a victory over the rebels and his rival in his army. As a Democratic congressman from Illinois and a close friend of Lincoln, McClernand enjoyed a political alliance with the President. However, his position as a political general had its drawbacks. While serving as second in command at Belmont and later as a division commander at Donelson, Grant knew that if he failed, he would be next in line. Despite this, Grant maintained direct communication with Lincoln, bypassing the chain of command, and freely offered his advice and criticism of others. His ultimate goal was to secure an independent command.

Grant’s Bayou Operations

From January to March 1863, Grant’s basic plan was to get close to Vicksburg with his army so that in the Spring, he could be ready, without being exposed to the town’s formidable artillery. Grant sought to create alternative routes that could serve as highways for his troops by preparing waterways in the vicinity,. These operations involved a series of seven initiatives or “experiments” that took place from January to March 1863. Although all of these attempts ultimately failed, Grant’s willingness to explore various possibilities demonstrated his fearlessness in the face of potential failure. This mindset, characterized by creativity and thoughtfulness, ultimately led to his success. Grant’s relentless pursuit of alternative strategies showcased his determination to find a solution, even if it meant considering unconventional approaches.

Grant’s Canal

One in particular deserves special mention. Grant’s Canal was an attempt to create a canal through De Soto Point in Louisiana, across the Mississippi River from Vicksburg, Mississippi. In 1862, Farragut had explored the option of bypassing the fortified cliffs by constructing a canal across the river’s bend, the De Soto Peninsula. Brigadier General Thomas Williams was sent to De Soto Point with 3,200 men to dig a canal capable of bypassing the Confederate defenses. Diseases, especially malaria, yellow fever, and dysentery, as well as falling river levels, prevented Williams from successfully constructing the canal, and the project was abandoned. In January 1863, the project regained momentum when General Grant took an interest in its potential.

Encouraged by Grant, who had received favorable feedback from the navy regarding President Lincoln’s support, Sherman’s troops resumed excavation in late January 1863. Mockingly referred to as “Butler’s Ditch” by Sherman, referencing Major General Benjamin Butler, who had initially dispatched Williams for the task, the canal was a mere 6 feet wide and 6 feet deep. Recognizing the extensive engineering challenges, Grant initiated modifications by relocating the entrance upstream to capitalize on a stronger current.

Reports indicated that the water in the canal was stagnant and lacked any current, necessitating the need for a deeper channel for the Union Navy ironclads to navigate through. Grant, recognizing this issue, also gave orders to widen the canal. However, as the month drew to a close, it became evident to Grant that the canal project would not be successful. Union officers who visited later discovered that the water level was only 2 feet and observed the absence of any current, despite earlier reports of depths reaching up to 8 feet and widths up to 12 feet in certain areas. The situation took a turn for the worse when a sudden rise in the river caused the dam at the canal’s entrance to break, resulting in flooding in the surrounding area. Consequently, the canal began to fill up with sediment and backwater. In a desperate attempt to salvage the project, two large steam-driven dipper dredges named Hercules and Sampson were deployed to clear the channel. However, their efforts were thwarted by Confederate artillery fire from the bluffs at Vicksburg, forcing them to retreat. By the end of March, all work on the canal was abandoned.

In April 1876, the Mississippi River changed course, forming a channel through De Soto Point. Vicksburg became isolated from the riverfront after the oxbow lake formed by the course change became cut off from the river. It was not until the completion of the Yazoo Diversion Canal in 1903 that Vicksburg regained its connection to the river. Although most of Grant’s Canal has been destroyed over time due to agricultural activities, a small section measuring approximately 200 yards in length still remains. It is worth noting that General Grant did manage to alter the course of the Mississippi River, a remarkable feat of engineering. However, this achievement came too late to hold any military significance.

Lake Providence

Brig. Gen. James B. McPherson constructed a canal stretching several hundred yards from the Mississippi River to Lake Providence, enabling access to the Red River via Bayous Baxter and Macon, as well as the Tensas and Black Rivers. This strategic waterway would allow Grant’s forces to link up with Banks at Port Hudson. By March 18, the connection was navigable, but the limited number of “ordinary Ohio River boats” provided to Grant for navigating the bayous could only accommodate 8,500 men. Although this was the only one of the bayou expeditions to successfully bypass the Vicksburg defenses, it was not enough for a successful Vicksburg operation. It did allow the possibility of sending reinforcements to Banks.

Yazoo Pass

The Yazoo Pass initiative aimed to reach the elevated terrain above Hayne’s Bluff and below Yazoo City by breaching the Mississippi River levee near Moon Lake, approximately 150 miles above Vicksburg, near Helena, Arkansas. This plan involved traversing the Yazoo Pass, an ancient route from Yazoo City to Memphis that had been obstructed by the 1856 levee construction, isolating the Pass from the Mississippi River to Moon Lake. The route would lead through the Coldwater River, then the Tallahatchie River, and finally into the Yazoo River at Greenwood, Mississippi. It may also have been intended as a method to raid the railroad bridge at Grenada.. Despite the Union’s efforts to blow up the dikes on February 3, obstacles such as low-hanging trees and deliberate Confederate obstructions hindered progress. These setbacks allowed the Confederates to hastily erect “Fort Pemberton” near the junction of the Tallahatchie and Yalobusha Rivers, effectively repelling the Union naval forces.

Steele’s Bayou

On March 14, Admiral Porter attempted to reach Deer Creek by sailing up the Yazoo Delta through Steele’s Bayou, which is located just north of Vicksburg. The purpose of this maneuver was to outflank Fort Pemberton and enable the landing of troops between Vicksburg and Yazoo City. However, the Confederates obstructed their path once again by felling trees and causing the paddlewheels of the boats to become entangled with willow reeds. This situation raised concerns that Confederate troops might seize the boats and sailors, necessitating Sherman to move troops by land to rescue them.

Duckport Canal

Another canal project known as the Duckport Canal was initiated to create a waterway from Duckport Landing to Walnut Bayou, aiming to allow lighter boats to bypass Vicksburg. However, by the time the canal was nearly completed on April 6, the water levels had significantly decreased. As a result, only the lightest flatboats were able to navigate through the canal, rendering it ineffective for larger vessels.

Milliken’s Bend

The main challenge Grant faced in dealing with Vicksburg was its formidable position as a fortress situated on elevated bluffs along the river. The city boasted massive batteries that could outmatch any Union ships on the river. Additionally, Vicksburg was surrounded by nine major forts or citadels and protected by 172 guns, which commanded all possible approaches by both water and land. Furthermore, the city housed a garrison of thirty thousand troops, making it a highly fortified and well-defended stronghold.

Moreover, the turn in the river beneath the town ensured that any naval force would face immediate and devastating bombardment, making it a formidable barrier for potential invaders. However, the protected northern invasion route through a maze of swampy bayous posed a significant obstacle for Grant’s army. While his troops could camp on the west side of the river, the logistics of launching an attack from that position were complex and uncertain. The necessity of eventually crossing the river to the other side raised questions about how the supply line and reinforcements would be managed during the movement.

Grant wasn’t actually directly across the river, because the large Cypress Swamp comprises the west bank. He was located at Milliken’s Bend, upriver from the 180-degree turn in the river. Despite the seeming disadvantage of being further away, this positioning allowed for a level of strategic ambiguity that Pemberton underestimated. Milliken’s Bend, situated in Louisiana about 15 miles upriver from Vicksburg, served as a crucial staging area for Grant’s army by 1863. The distance from Pemberton’s forces provided Grant with the element of surprise and control over the river traffic, enhancing his strategic advantage.

The construction of bridges, corduroy roads, and the clearing of swamps by McClernand’s troops from Milliken’s Bend to the proposed river crossing at Hard Times, Louisiana, below Vicksburg, demonstrated the meticulous planning and effort required to overcome the challenging terrain. By filling in the swamps and creating a 70-mile road by April 17, the Union forces were able to establish a vital connection for their movements toward Vicksburg. This logistical feat showcased the determination and resourcefulness of Grant’s army in navigating the difficult landscape to achieve their strategic objectives.

April brought receding waters and the emergence of roads from Milliken’s Bend to points downriver on the west bank. Grant planned to march his troops over those roads to a location where he could ferry them to the east bank of the river.

The Plan Emerges

Grant pored over maps and developed a plan requiring naval cooperation by January. Grant expressed that the next step was to get south of the city when he first landed at Young’s Point, in late January. In early February 1863, Grant conveyed to General Halleck and Admiral Porter his conception for the campaign. He later convened a staff meeting to outline his intentions. He expressed his desire to lead his army south of Vicksburg, cross the river, and sever the vital railroad link between Vicksburg and Jackson. However, despite his clear plan, Grant chose to delay the execution of his strategy until Spring. According to Grant’s account in his memoirs, he attributed this delay to the high water levels of the river in January, which made it impractical to commence the campaign at that time.

Grant directed his army to march southward along the west bank of the Mississippi River, aiming to position his forces well below Vicksburg. The next step in his plan involved transporting his troops across the river, a task that required navigating past the formidable guns of the city. Once safely on the Mississippi shore south of Vicksburg, Grant intended to strike inland, engaging any Confederate forces encountered along the way, with the ultimate objective of capturing Vicksburg. Grant’s meticulous planning involved extensive study of maps and charts, as he single-handedly devised this approach. However, his subordinates, including Sherman, McPherson, and Logan, expressed reservations about the plan, deeming it too risky. By using the new road, and a large Bayou, Grant was capable of reaching Hard Times Landing without being detected. The army marched south on the west side of the Mississippi River and crossed the river south of Vicksburg at a place named Hard Times.

Hard Times is just beyond Big Cypress swamp. At that location, the Mississippi River takes a wide inward turn. Bayou Vidal, which may have once been the main river channel, provided a direct route for Grant’s forces. This route was approximately six miles beyond Grand Gulf on the opposite side of the river, where they boarded transports to cross over to Bruinsburg. Grant recognized the significance of this route and understood that he could continue to utilize it for transporting supplies as long as necessary.

Grant had three options for attacking Vicksburg: The first option was to return to Memphis and approach the city from the north and east via an overland route. However, Grant dismissed this option as it would have negatively impacted morale to retreat. The second option involved directly assaulting the city by crossing the Mississippi River. Grant rejected this option, believing it would result in a significant loss of life or even defeat. The third option was to march his troops down the west bank of the Mississippi, cross it, and approach the city from the south and east. Upon hearing Grant’s plan, Sherman expressed doubts and suggested that Grant should reconsider option #1 and return to Memphis. Blair after the war also expressed his skepticism at the time.

The Naval Rendezvous

Grant’s particular genius in the war was his brilliant collaborations with the navy. His victories at Forts Donelson and Henry for example were made possible by the combination of ground and water approaches. In that sense, the concept of combined arms forces was an innovation General Grant developed. Vicksburg is the outstanding application of the model.

The Union troops needed to rendezvous with their Navy to cross into Confederate territory, but the success of this operation depended on the ability of the boats to evade the guns defending Vicksburg. It was crucial for there to be an adequate number of gunboats and transport ships positioned south of the city to ensure the plan’s success. Once the Union Navy had navigated downstream past Vicksburg, there was no turning back due to the strong river current.

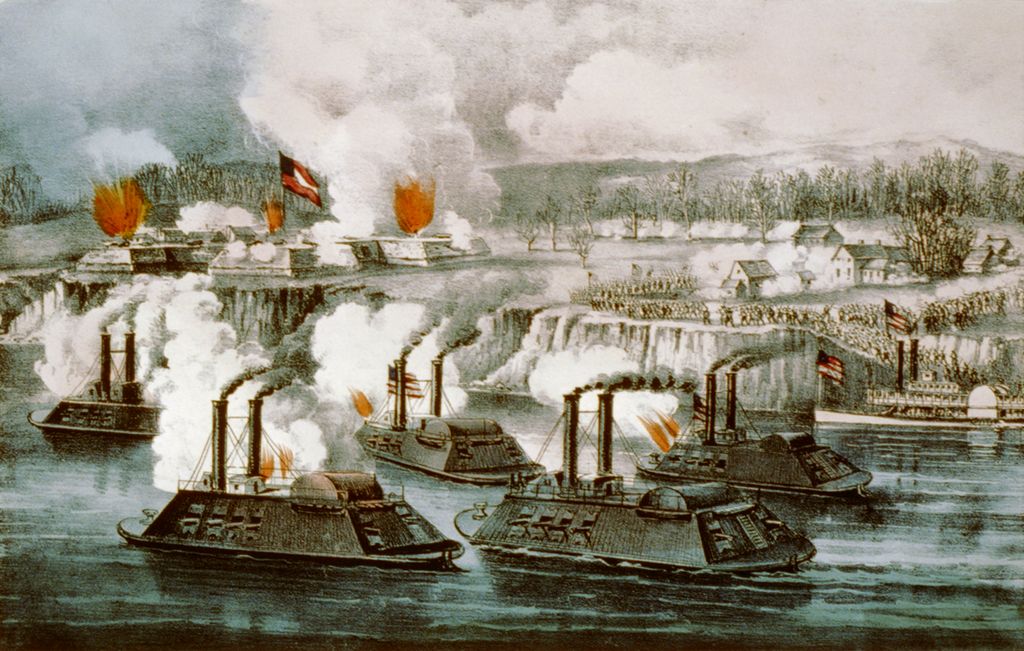

On the evening of April 16, two weeks before the planned river crossing, Admiral David Porter guided the Union fleet past the Confederate batteries at Vicksburg to join forces with Grant. Despite being detected by Confederate lookouts as they rounded De Soto Point, the fleet pressed on and engaged in battle with the Confederate batteries. Despite sustaining damage from enemy fire, the Union fleet successfully fought their way through to rendezvous with Grant.

Porter directed to ensure the concealment and protection of the boilers on the steamships by utilizing barriers made of cotton, hay bales, and bags of grain. This strategic measure would prove beneficial in the future as well. Additionally, to provide an extra layer of defense, coal barges, and surplus vessels were securely fastened to the sides of the critical vessels. Commencing at 10 pm on April 16, Porter assumed command of a fleet consisting of seven ironclad gunboats, four steamers, the tug Ivy, and a variety of towed coal barges, as they embarked on a downstream journey. The Union vessels were illuminated by Confederate bonfires, becoming targets for a relentless two-hour barrage from the Vicksburg guns. Despite the intense fire, the ironclads and supply-laden transports successfully navigated past the Vicksburg guns. The Confederate cannons unleashed a total of 525 rounds, resulting in sixty-eight hits. Remarkably, only one vessel was lost, and there were no casualties among the crew. Additionally, the Confederates had placed ropes strung across the river with explosives attached that could be moved by pulleys.

Grant realized that it would be impossible to provide his army with supplies using the muddy west bank road. As a result, a second convoy was organized to address this issue. On the night of April 22, six transport vessels, without any escorts, were tasked with towing barges loaded with 100,000 rations and other essential supplies, attempting to pass through the Vicksburg batteries. Grant, recognizing the importance of additional supplies, ordered another group of vessels to bring reinforcements one week later on the same night. This time, six protected steamers, under the command of Colonel Clark Lagow from Grant’s staff, towed twelve barges filled with rations. Despite facing heavy fire from the Vicksburg batteries, five of the steamers and half of the barges successfully made it through. The vessels were primarily manned by army volunteers from “Black Jack” Logan’s division, as the civilian crews were too fearful to navigate through the dangerous Vicksburg gauntlet. Although the run was mostly successful, the leading vessel, a hospital ship, was unfortunately sunk, resulting in the loss of two lives. Meanwhile, by cutting a new road through the swamp, when necessary, McClernand’s corps worked its way south and was joined by one of McPherson’s divisions.

Diversionary Tactics

To enhance the element of deception during his planned landing, Grant employed diversionary tactics to divert Pemberton’s attention away from the south and the river crossing site. These tactics were executed through two well-conceived feints.

Snyder’s Bluff

While he was moving south with McClernand and McPherson on the west (Louisiana) bank, Grant had Sherman’s Fifteenth Corps threaten Vicksburg from the north. On April 27, Grant ordered Sherman to proceed up the Yazoo River and threaten Snyder’s Bluff northeast of Vicksburg. On the 29th, Sherman debarked ten regiments of troops and appeared to be preparing an assault while eight naval gunboats bombarded the Confederate forts at Haines’s Bluff.

Sherman’s division remained north of Vicksburg. General Sherman led a highly successful diversionary attack by utilizing a combined naval and infantry operation. Blair’s division, consisting of eight gunboats and ten transports, secretly and quietly moved to the mouth of Chickasaw Bayou the night before the operation. At 9 am, all gunboats, except one, opened fire on the enemy forces in the bayou, while one gunboat and the transports moved upstream.

At the Battle of Snyder’s Bluff, the troops proceeded upstream until approximately 6 pm, crossed Blake’s Levee, and launched an assault on the artillery near Drumgold’s Bluff. This location was significantly north of Vicksburg, diverting focus from the ongoing activities downstream. The attack faced insurmountable challenges due to the strategic positioning of batteries on Drumgold’s and Snyder’s Bluffs, as well as the course of the Yazoo River that General Sherman’s forces had to navigate.

At first, heavy casualties were sustained. The next morning more troops were deployed, but the difficult terrain of swamps and marshes posed formidable barriers to any progress. Sherman eventually retreated to Milliken’s Bend, realizing that his contingent, which constituted only a fraction of General Grant’s overall command, would likely have failed to capture the bluffs even if a direct attempt was made.

Sherman withdrew on May 1 and hastily followed McPherson down the west bank of the Mississippi. His troops were ferried across the river on May 6 and 7.

This diversionary maneuver effectively drew Pemberton’s attention away from Grant’s actual landing site. Pemberton sent 3,000 troops that had been marching south to oppose Grant.

Grierson’s Raid

The success of this diversion was remarkable, as it involved a daring cavalry raid that originated from La Grange, TN and penetrated central Mississippi on April 17. This marked the commencement of a relentless 17-day campaign characterized by constant movement, widespread devastation, and frequent clashes. Upon its conclusion, General Grant aptly hailed it as “one of the most remarkable cavalry exploits of the entire war.”

Under the leadership of Grierson, a force of 1,700 soldiers from the 6th and 7th Illinois, as well as the 2nd Iowa Cavalry regiments, embarked on this audacious mission from La Grange. Over the course of 17 days, Grierson’s troops covered a staggering distance of 800 miles, engaging Confederate forces repeatedly. They successfully disrupted two vital railroads, took numerous prisoners and horses, and inflicted significant damage to enemy property. Their journey culminated in Baton Rouge on May 2, where Grierson joined forces with Nathaniel Banks in the ongoing siege at Port Hudson.

By skillfully diverting attention to the north and east of Mississippi, this raid effectively diverted Confederate focus away from the gathering of troops at Grand Gulf. Through the deployment of small patrols and deceptive maneuvers, Grierson managed to confuse the enemy regarding his true location, intentions, and direction. Operating deep within enemy territory, his forces systematically dismantled rail infrastructure, liberated enslaved individuals, razed Confederate storehouses, disabled locomotives, and obliterated commissary stores, bridges, and trestles. The lack of a viable response from General Pembleton further contributed to the raid’s triumph. While Forrest was engaged in Alabama, combating Streight’s Raid, other Confederate cavalry units were dispatched but proved unable to catch up with Grierson’s swift movements. This strategic diversion ultimately hindered Pemberton’s ability to effectively counter Grant’s advance from the south, as he found himself inadequately equipped to confront the Union forces due to the distractions caused by Grierson’s audacious exploits.

Find that piece of interest? If so, join us for free by clicking here.

Further Reading:

· Donald L Miller, Vicksburg: Grant’s Campaign That Broke the Confederacy. Simon and Schuster, 2019.

· Grant’s Memoirs

· Sherman’s Memoirs

· Grant by Chernow

· https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/vicksburg

· https://www.historynet.com/battle-of-vicksburg

· https://civilwarmonths.com/2023/04/15/vicksburg-grant-and-porter-assemble/amp/

· https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/achenblog/wp/2014/04/25/ulysses-s-grant-hero-or-butcher-great-man-or-doofus/

· https://www.historynet.com/vicksburg-the-campaign-that-confirmed-grants-greatness/

· https://www.vicksburgpost.com/2003/01/27/water-returned-to-citys-doorstep-100-years-ago/?fbclid=IwAR1X5nFZ8F-l_0sbr3Ki1HBygBiPb-GCgxl4aBCznjSOgKAvVdURVJUvJDA

· https://www.nps.gov/vick/learn/nature/river-course-changes.htm?fbclid=IwAR3mflQUgR8JaUEIcrm2v_lLlfdGup44_XwzxIcJ1mTAyyCT2h_umfcT2Sc

· https://www.historynet.com/americas-civil-war-colonel-benjamin-griersons-cavalry-raid-in-1863/

· https://www.historynet.com/griersons-raid-during-the-vicksburg-campaign/

· https://www.thoughtco.com/major-general-benjamin-grierson-2360423

· https://emergingcivilwar.com/2021/04/29/that-other-cavalry-guy-benjamin-h-grierson/

· https://www.historyonthenet.com/grant-vicksburg

· https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/port-gibson

· https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/entries/battle-of-port-gibson/

· https://www.nps.gov/vick/learn/historyculture/battleportgibson.htm

· https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/grants-vicksburg-supply-line

· https://www.historynet.com/mississippi-nightmare/

· https://www.thoughtco.com/battle-of-champion-hill-2360280

· https://www.rebellionresearch.com/battle-of-raymond?fbclid=IwAR1L1PcCwGRCFLg-Bv7neO1tG6cv7RsnmZO8kNvv5XVjUBkM6t3CiPtu96c_aem_th_AaSypV4shWeio-QbLLXIuILea41vtkZsruFEMGykenl_kK8dPEuWWYZiUP44s9G8ws4&mibextid=Zxz2cZ

· Klein LW, Wittenberg EJ. The decisive influence of malaria on the outcome of the Vicksburg campaign. Surgeon’s Call: The Journal of the National Civil War Medicine Museum. 2023; 28(1): 4 – 14.