Researchers calculated that the human brain processes thought at a speed of ten bits per second.

Andriy Onufriyenko via Getty Images

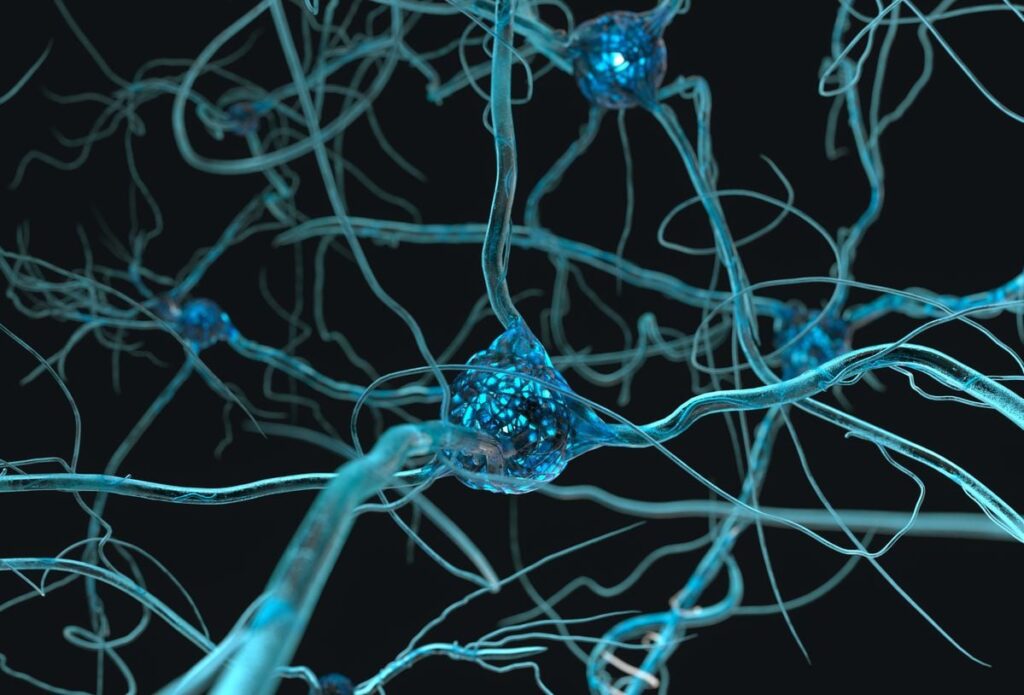

The human brain is a biological marvel, stuffed with some 86 billion neurons tangling in ways that even scientists have not yet been able to fully map and understand. Nevertheless, compared with modern technological devices, it’s fair to say that humans live life in the slow lane, given the relatively sluggish speed at which our brains process information.

An average Wi-Fi connection in the United States has a download speed above 260 million bits per second. A phone call takes up approximately 64,000 bits per second. Our brains, on the other hand, think at a mere ten bits per second, according to new calculations published this month in the journal Neuron.

“It’s a bit of a counterweight to the endless hyperbole about how incredibly complex and powerful the human brain is,” study co-author Markus Meister, a neuroscientist at the California Institute of Technology, tells Carl Zimmer of the New York Times. “If you actually try to put numbers to it, we are incredibly slow.”

The authors came by their number after examining scientific papers about human feats of speed, then applying methods from the field of information theory to calculate how quickly the brain processes thoughts in these situations. For example, advanced typists hammer away at the keyboard at 120 words per minute, but all that finger dexterity still only translates to ten bits per second of information processing, the researchers conclude. Elite video gamers seem to have lightning-fast reaction times and make split-second decisions, but even their thoughts max out at ten bits every second.

The team wondered whether human thinking speed could be hampered by our hardware—in other words, is the body simply too slow to respond to our train of thought? To eliminate this possibility, the researchers looked to a less physically intensive pastime: blind speedcubing, where participants study a Rubik’s cube, then put on a blindfold and solve it as quickly as they can. Here, the act of perception—examining the cube and mapping out the solution—features heavily, and it requires little movement compared with the cube-solving phase. But even in this motor-light exercise, cognitive traffic comes in at just under 12 bits per second.

Our chaotic surroundings, meanwhile, provide far more than just ten bits per second of information—and to be fair, the human senses can match this delivery. In one second, our sensory systems can bring in some ten billion bits of data, with about 1.6 billion bits processed by a single eye alone. But as for conscious thought in the brain, that harried pace of information exchange slows to a relative crawl. Our eyes might capture a wide view of our surroundings, but our brains focus on only a small portion of it at a time.

This slow thinking speed means we’re shedding vast quantities of information input and selecting only a tiny sliver to work with. Ten bits per second “is an extremely low number,” Meister says in a statement. It’s a paradox, he adds, that despite the wealth of data bombarding our senses, we make do with so little of it. “What is the brain doing to filter all of this information?”

One hypothesis is that our bodies were built for a slower era. The ability to operate on ten bits of information per second has been enough for our ancestors to survive. The earliest brains might have evolved for simple navigation, per the statement, and only needed to follow one “path” of thought at a time. Evolutionarily speaking, that intellectual speed was enough for humans to adapt to the slow-moving natural world. But now, the digital world shifts at a much faster pace—outstripping the thought capacity of our physiological systems.

“Nature, it seems, has built a speed limit into our conscious thoughts, and no amount of neural engineering may be able to bypass it,” Tony Zador, a neuroscientist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory who was not involved with the research, says to Scientific American’s Rachel Nuwer. “Why? We really don’t know, but it’s likely the result of our evolutionary history.”

Notably, the new study only looks at conscious tasks, neglecting the whirr of other cognitive processes that occur just beneath our awareness. The brain is still working relentlessly when we’re standing or walking, for instance, and if that information had been included in the team’s speed calculation, they would “end up with a vastly higher bit rate,” Britton Sauerbrei, a neuroscientist at Case Western Reserve University who was not involved in the new work, tells the New York Times. Nevertheless, he agrees with the study authors that the brain capacity involved in deliberate tasks transmits little data. “I think their argument is pretty airtight,” he says.

Another shortcoming of our brains compared with computers and smart devices: our brains fall short at parallel processing. We work best handling one thought at a time, instead of balancing several in one go. Humans are no good at multitasking, despite our illusion of getting more work done when we jump between activities, according to Jack Knudson of Discover magazine. That’s because we don’t juggle two or more tasks at once as much as we toggle between them, usually at the expense of our focus. Overall performance and efficiency tend to suffer as a result, despite our best intentions to wring more productivity from our days.

The latest calculations on human brain speed cast doubt on the arguments for neural-computer interfacing devices meant to accelerate our communication speed, per the statement. Now knowing that the human mind is the bottleneck, the new study provides food for thought to technology start-ups chasing this buzzy integration of the computer with the mind.

At the end of the day, speed isn’t necessarily everything when it comes to thought. Studies have shown that slowing down our information processing can help things stick in the brain. Perhaps the most salient example is writing by hand, which is often more time-intensive than keyboard punching. But there’s something about engaging our complex motor skills and the visual senses that might help wield our brains to the fullest: Studies have concluded that taking pen to paper helps young children retain the alphabet, and note-jotting adults better digest new concepts during lectures, compared to typists.

As dizzying as the pace of technology-infused life is in the digital age, these findings suggest we still have ample reason to be the tortoise rather than the hare.