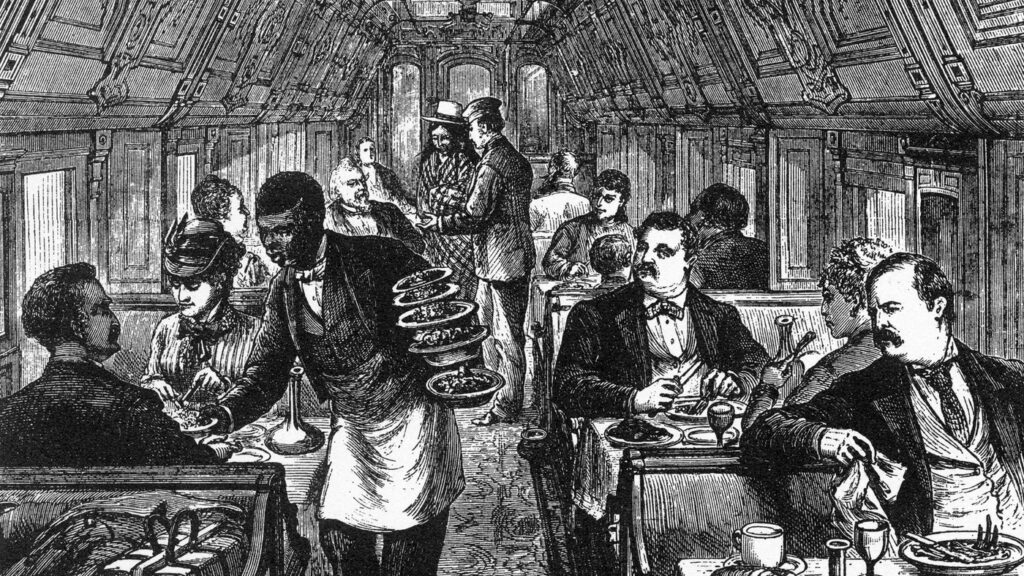

Illustration of Luxurious American Pullman Dining Car, 1877.

Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Getty Images

Illustration of Luxurious American Pullman Dining Car, 1877.

Getty Images

Tipping is a norm in the United States. But it hasn’t always been this way. It’s a legacy of slavery and racism and took off in the post-Civil War era. Almost immediately, the idea was challenged by reformers who argued that tipping was exploitative and allowed companies to take advantage of workers by getting away with paying them low or no wages at all.

The case against tipping was captured in William Rufus Scott’s 1916 anti-tipping polemic, The Itching Palm, a book that railed against the practice and its negative impacts on society. The movement had momentum: anti-tipping associations were formed and anti-tipping laws passed. Yet, tipping held on to its place in American culture and the anti-tipping movement failed to eradicate it. We still tip today and, for some, this remains a contentious issue.

Tipping began in the Middle Ages in Europe when people lived under the feudal system. There were masters and servants, and there were tips. Servants would perform their duties and be given some pocket change in return. This was still custom in the 18th century and transitioned from masters and servants to customers and service industry workers.

Throughline’s Rund Abdelfatah and Ramtin Arablouei spoke to Nina Martyris, a journalist who has written about the history of tipping in the United States, to find out how tipping—once deemed a “cancer in the breast of democracy”— went from being considered wholly un-American to becoming a deeply American custom.

Below are highlights from a conversation with Martyris on the latest episode of Throughline. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

NINA MARTYRIS: Until the Civil War in America, there was no tipping. It was a European thing. But then Americans began to travel to Europe and brought this custom back. At the same time, immigrants were coming to America by the boatload from Europe, most of them poor, [and] had been working in Europe and were used to the tipping system. So in every way it was seen as a European import and there was huge opposition to it, because of its feudal nature.

RAMTIN ARABLOUEI: What was the principal argument against it in the 1800s? Why did some people find it distasteful?

MARTYRIS: They found it distasteful and un-American because it was feudal. And when you give a tip, you establish a class system. By tipping somebody, you rendered him your inferior, your moral inferior, your class inferior, your social and economic inferior. So it was a caste bound system and it was an old world custom and it reeked of feudalism. It was called servile and it was called a bribe. It was called a moral malady. It was called blackmail. It was called flunkeyism. People railed against it.

RUND ABDELFATAH: What happens in the Civil War that changes the equation? Can you explain how the fact that freed Blacks were now entering the workforce in waves affects this tipping debate?

MARTYRIS: Suddenly there were millions of young men, old men, young women, older women who now were free, but had no jobs. They didn’t have land. They weren’t educated because they never got a chance to be educated. And at about this time, restaurant owners began to hire them in their restaurants as restaurant workers. And they didn’t pay them, because the tipping system had come in. And they had to make their wage through tips.

On the Pullman Car Company:

MARTYRIS: The Pullman Car Company was started by George Pullman. He was an engineer in Chicago, and he saw that trains were very uncomfortable. So he designed this nice posh carriage, you know, like business class. One of the big perks was to have a porter there to assist you with your baggage, to smile, to make your bed, to amuse your kids, to answer the bell when you rang it. And this growing American middle class who wanted to travel now that the war was over, this was like a big thing for them to go by train and to have all their needs met. Because they couldn’t afford to have a servant or staff in their house, but they had it on the train. And who did Pullman hire for his porters? Only Black men. And not just Black men, Southern Black men. Why? He says because the plantation, these are his words, ‘has more or less trained them to be pleasing to the customer.’ So they were paid a wage. They were paid $27.50 a month. Nobody could live on that wage – the rest of it was made up in tips. And that became the place where tipping really began to spread, because the Pullman cars traveled all across the country.

ARABLOUEI: So people were paying for an upper class experience, and he created this fantasy experience for people and as a result needed to be able to exploit the workers in order to kind of facilitate that demand.

MARTYRIS: Yes. And, so, you have to say, why did these African-American men then work for him? Well, for many reasons. One, they got to travel the country, something that in their wildest dreams they had never done before. Two, there were not many jobs available at the time. And it wasn’t that punishing hard work that they had been used to working on plantations. It was a prestigious thing for them to join the Pullman car companies and work as porters. The conductors were always white men. The porters were always Black.

ABDELFATAH: When Pullman happens, it sounds like it launches tipping in more spaces and through more professions. And what is the reaction among those who are against tipping?

MARTYRIS: People complained about it all the time because it was still fairly new then in the 1870s and 1880s. They complained about it all the time, saying that everywhere we go, it’s like a shakedown and we have to pay, pay and we pay twice. We pay for our food and then we pay for the service. Why should we have to do all this? When William Taft ran for president, about 1908, one of his biggest boasts was that he didn’t tip his barber. And so then he became what they call the patron saint of the anti-tipping crusade.

MARTYRIS: Many of the comments in the media about tipping bring out the racist values of the time. For instance, a journalist named John Speed, writing in 1902, recalled, “Negroes take tips. Of course, one expects that of them. It is a token of their inferiority. But to give money to a white man was embarrassing to me. I felt defined by his debasement and civility.” What he’s saying is, if you’re a Negro, if you’re Black, to accept a tip is OK because civility is a token of inferiority, but to be a white man and accept a tip is unpardonable.

On restaurant workers:

[NOTE: In 1938, as part of the New Deal, The first federal minimum wage law was established in American history. Minimum wage was set at 25 cents an hour.]

MARTYRIS: But guess what? Restaurant workers weren’t included. And so it became law that the restaurant owners do not have to pay twenty five cents an hour. They excluded them from the minimum wage. And that kind of codified the fact that you’re paying your workers only through tips. And then tips became legal. The law had taken them into account in 1938 by excluding restaurant workers. That’s sort of the nail in the coffin for ever getting a fair wage.

ABDELFATAH: There’s something striking to me about the fact that the minimum wage coming into the picture sort of shifts attention away from tipping. I mean, that’s what it sounds like. It sounds like suddenly this debate that had been going on for decades at that point in American life is sidelined by the fact that suddenly you have this new thing, a minimum wage coming onto the scene. I wonder how you see those two histories interacting in that moment?

MARTYRIS: You’ve created a two-tier system among your workforce. And I think that was the beginning of the rot, which we are paying a price for till today.

If you would like to learn more about tipping: