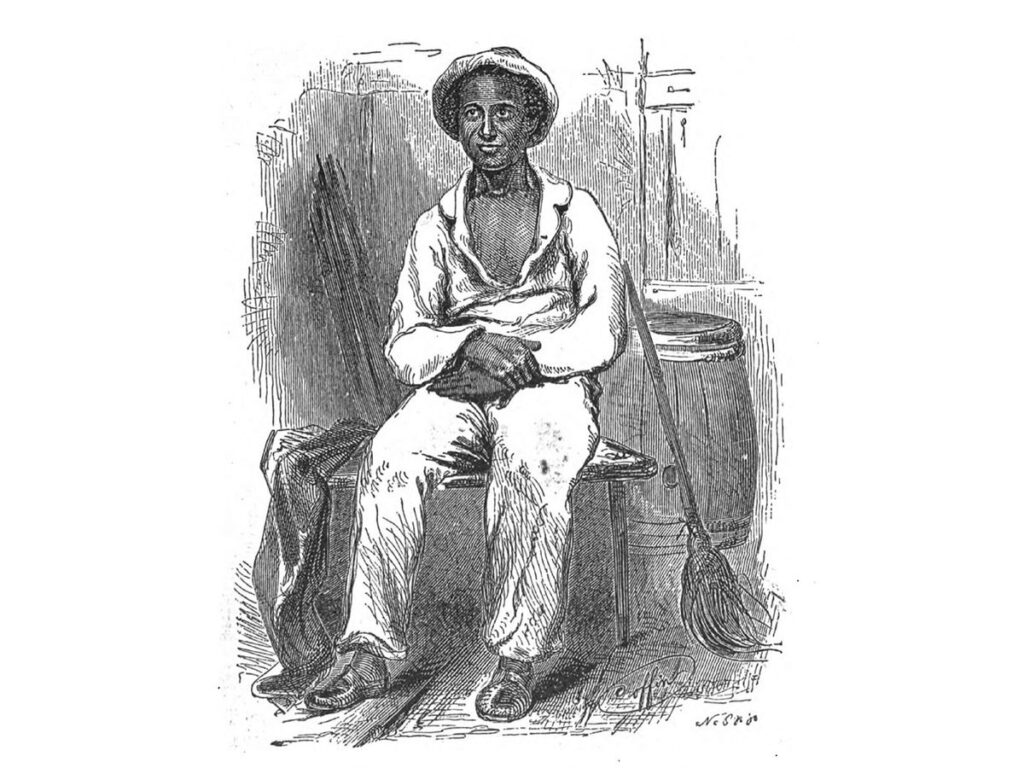

A sketch of Solomon Northup from his memoir, Twelve Years a Slave

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Solomon Northup was a free Black man living in Saratoga Springs, New York—a married, educated carpenter and musician—when two white men asked him to be their fiddle player in Washington, D.C in 1841. Interested, 33-year-old Northup accompanied the men to the nation’s capital, where they drugged him, tied him up and dropped him in the Williams Slave Pen.

Northup was no longer free. He would spend the next 12 years of his life enslaved, until he was finally freed on this day in 1853.

“It was like a farmer’s barnyard in most respects, save it was so constructed that the outside world could never see the human cattle that were herded there,” Northup later wrote of the slave pen in which his ordeal began. “Its outside presented only the appearance of a quiet private residence. A stranger looking at it would never have dreamed of its execrable uses.”

Northup’s kidnappers had stolen his freedom papers—the documentation that designated him a free African American in the United States, where slavery would be legal for another two decades. From Washington, he was taken first to New Orleans, then to multiple plantations in central Louisiana.

Scenes from Northup’s memoir, Twelve Years a Slave

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

A man named William Prince Ford bought Northup, who had been renamed “Platt” by the slave traders. Later, Northup recalled that Ford rewarded him for his work and behaved leniently toward him “while, under subsequent masters, there was no prompter to extra effort but the overseer’s lash.” Ford’s lenience came to an abrupt end when he sold Northup to a carpenter in 1842. The carpenter, in turn, sold him once more to plantation owner Edwin Epps for $1,500.

Epps turned out to be an especially sadistic master. He developed a “twisted, pathological attachment to his female slave, Patsey,” notes educator Laurel Sneed. Northup later wrote that Epps rarely went a day without whipping at least one of the people he enslaved.

“It is the literal, unvarnished truth that the crack of the lash, and the shrieking of the slaves, can be heard from dark till bed time on Epps’ plantation, any day almost during the entire period of the cotton-picking season,” Northup recalled. “To speak truthfully of Edwin Epps would be to say—he is a man in whose heart the quality of kindness or of justice is not found.”

In the summer of 1852, Epps hired a white Canadian carpenter named Samuel Bass to do some work for him. Bass was opposed to slavery and compassionate to Northup’s plight; he agreed to write a letter to two white storekeepers back in Saratoga, New York—friends of Northup’s—telling them of Northup’s enslavement and whereabouts.

The shopkeepers, William Perry and Cephas Parker, in turn told Northup’s wife, Anne, and his attorney, Henry Bliss Northup, a relative of the former enslaver of Northup’s father. The attorney gained permission from New York’s governor to go south and rescue Northup, and on January 3, 1853, he arrived at Epps’ house with the local sheriff. They escorted Northup off the plantation and legally obtained his freedom at a local courthouse the next day.

Epps regarded Black people as “chattel,” as “mere live property,” Northup later wrote. “When the evidence, clear and indisputable, was laid before him that I was a free man, and as much entitled to my liberty as he … he only raved and swore, denouncing the law that tore me from him, and declaring he would find out the man who had forwarded the letter that disclosed the place of my captivity, if there was any virtue or power in money, and would take his life.”

Northup was reunited with his family on January 21, 1853. Over the next few months, Northup and editor David Wilson wrote a book detailing his story. Titled Twelve Years a Slave, the memoir was published that summer. It sold 17,000 copies in four months—nearly 30,000 by 1855. A 2013 film adaptation of Northup’s story won the Academy Award for Best Picture.

After his best-selling book was published, Northup became an active member of the abolitionist movement, giving speeches throughout the Northeast, staging plays based on his story and likely helping enslaved people on the Underground Railroad. He disappeared from the historical record after a final public appearance in Ontario, Canada, in August 1857. The time and circumstances of his death are unknown.