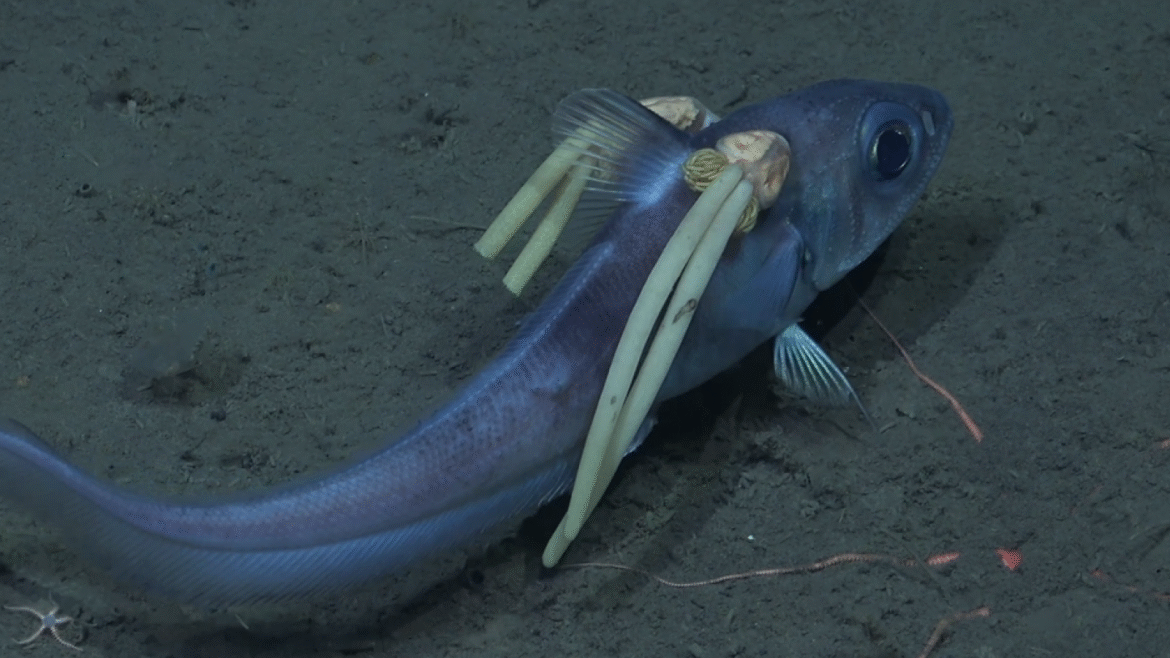

Shocking new footage shows a pair of bloodsucking parasites latched onto the head of a deep-sea rattail fish.

In the video, which the Schmidt Ocean Institute shared in a Facebook post, two copepods — small crustaceans — are positioned on either side of their host’s head. Long egg sacs attached at the back of the parasites make it look like the fish is sporting a pair of pig tails.

“They feed on blood and fluids from their host using their scraping mouth parts that are embedded in the muscle of the fish,” James Bernot, an evolutionary biologist at Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History who was not on the expedition, told Live Science in an email.

Scientists captured the footage at a depth of 1,604 feet (489 meters) during an expedition to examine the seafloor and biodiversity of the South Sandwich Islands, a chain of 11 subantarctic volcanic islets in the South Atlantic Ocean.

The copepods are a species called Lophoura szidati, and are latched onto the head of a rattail fish from the genus Macrourus, representatives wrote in the Facebook post.

Related: Watch bright red blood-sucking parasite feast on gulper eel in rare, deep-sea footage

Macrourus are commonly known as grenadiers or rattails because of their large heads and slender tails. These widespread deep-sea fish occupy the cold waters of the North and South Atlantic Ocean, as well as the Southern Ocean that borders Antarctic waters, and can be found at depths from 1,312 to 10,450 feet (400 to 3,185 m).

Knowledge of deep-sea fish parasites in Antarctic waters is scarce, but L. szidati, is one of the most common parasites found on Macrourus species in this region.

L. szidati is part of the family Sphyriidae. Females of this species have been observed using their mouth parts to bore into the bodies of various fish and feed on their host’s muscle tissue.

“These copepods are mesoparasites, meaning they are partly inside and partly outside of their host,” Bernot said, adding that in the video the middle and back end of the copepods stick out of the fish, while the anterior, or head-end of their body is embedded in the fish.

Many copepod parasites have multiple stages in their life cycle and typically find their hosts while in their larval stage. These tiny larvae bury themselves within the host’s skin and begin feeding. During this time they metamorphose and develop anterior holdfasts that serve as anchors to keep them attached to their hosts as they grow.

In the video, each parasite carries a pair of sacs containing hundreds of eggs. “Copepods are surprisingly good mothers for invertebrates,” Bernot said. “They carry their eggs in sacs attached to their body until the eggs hatch into swimming nauplius larvae that will molt through several larval stages and eventually go on to find their own host.”

Very little is known about the life cycle and lifespan of these parasites, but they are permanent fixtures to the fish and likely live for several months as they grow from a near microscopic size, Bernot said.

“Even after the parasite dies, remnants of the embedded head can still be found in their host for many years,” Bernot noted.