Stacys are horrible machines to work on. Nobody likes being inside of one. The daughterboards don’t have keyed connectors (including the power supply!) and are constantly attempting to come free, the display “cable” is actually a Medusa’s wig of wires that like to short (!), the top case is a huge bulky sheet of increasingly fragile plastic that somehow has to fit around the floppy drive yet down on the keyboard simultaneously, and the entire laptop is an uneasy sandwich held together by a small set of screws in plastic races that all strip quicker than at a Hugh Hefner birthday party. So why do we tolerate this very bad, bad, bad, bad girl? Because most of us will never see the much lighter and streamlined STBook in the flesh, let alone own one. If you really want a portable all-in-one Atari ST system, the Stacy is likely the best you’re gonna do.

And we’re going to make it worse, because this is the lowest-binned Stacy with the base 1MB of memory. I want to put the full 4MB the hardware supports in it to expand its operating system choices. It turns out that’s much harder to do than I ever expected, making repairing its bad left mouse button while we’re in there almost incidental — let’s just say the process eventually involved cutting sheet metal. I’m not entirely happy with the end result but it’s got 4MB, it’s back together and it boots. Grit your teeth while we do a post-mortem on this really rough Refurb Weekend.

The Atari Stacy (often rendered STacy, but Atari’s product documentation always calls it Stacy or STACY) was one of Atari’s earliest portable systems and the ST line’s first. Effectively a gimped Mega ST in a laptop case (despite erroneous reports to the contrary it lacks a blitter, but does have an expansion slot electrically compatible with the Mega), it sports a backlit monochrome LCD, keyboard, trackball in lieu of the standard ST mouse, and a full assortment of ST ports including built-in MIDI. A floppy drive came standard; a second floppy or a 20 or 40MB internal SCSI hard disk was optional.

This was Jack Tramiel-era Atari and the promises of a portable ST system were nearly as old as the ST itself. For a couple years those promises largely came to naught until Atari management noticed how popular the on-board MIDI was with musicians and music studios, who started to make requests for a transportable system that could be used on the road. These requests became voluminous enough for Tramiel’s son and Atari president Sam Tramiel to greenlight work on a portable ST. In late 1988 Atari demonstrated a foam mockup of a concept design by Ira Velinsky to a small group of insiders and journalists, where it was well-received. By keeping its internals and chipset roughly the same as shipping ST machines, the concept design was able to quickly grow into a functional prototype for Atari World and COMDEX in March 1989. Atari announced the baseline 1MB Stacy with floppy disk would start at $1495 (about $3800 in 2024 dollars), once again beating its other 68000-based competitors to the punch as Apple hadn’t themselves made a portable Macintosh yet, and Commodore never delivered a portable Amiga. Sam Tramiel was buoyed by the response, saying people went “crazy” for the Stacy prototype, and vowed that up to 35,000 a month could be made to sate demand.

Reality, as usual, was more complicated. (Sorry about the water damage on this document but that’s as I received it.) The original spec sheet promised the machine could run on twelve (!) C batteries, and recharge Ni-Cad ones, but even alkaline cells could barely power a reasonably-equipped system for around a quarter of an hour. Some early units shipped with the battery hardware but Atari eventually completely gave up on the idea and removed it, condemning the machine to duty as a luggable. However, the section for the battery compartment persisted and was left completely empty.

Even more concerning was actually getting the unit approved for sale in any configuration. FCC Part 15 certification for the hard disk-equipped 2MB Stacy2 and 4MB Stacy4 was delayed until December 1989 and at first only as Class A, officially limiting it to commercial use, while the lowest-end 1MB floppy-only Stacy didn’t obtain clearance until the following year. We’ll see at least one internal consequence of this shortly (I did mention sheet metal). The delays also stalled out the system’s introduction in Europe and despite Tramiel’s avowed industrial capacity relatively few Stacys were ultimately sold. Based on extant serial numbers, the total number is likely no more than a few thousand before Atari cancelled it in 1991, though that’s greater than the successor ST Book which probably existed in just a thousand or so units tops. The Stacy’s failure to meet its technical goals (particularly with respect to size and power use) was what likely led to the ST Book’s development. Unfortunately, although a significant improvement on the Stacy, the ST’s decline in the market made sustaining the ST Book infeasible for Atari, and it was cancelled along with the entirety of Atari’s personal computer line in 1993.

This unit bears paperwork saying it was allegedly bought in 1991 but the serial number written on the paper doesn’t match the bottom of the machine, and given all the consolidated documents it came with, this paperwork may well have been from something else. Officially Stacys were to come standard with ST BASIC on disk, power supply, manual and a hernia belt’s worth of C cells, but this unit has a regular generic ST manual and a Stacy “Advanced Hard Disk Utilities” floppy instead of BASIC (and, secondarily, a copy of Blasteroids, because Mukor rules all galaxies). The paperwork also has the standard Atari limited warranty card covering a piddling 90 days.

There doesn’t appear to have ever been a Stacy-specific manual either. All of the copies I’ve seen are called a “STACY Addendum” and designed to complement the standard ST manual. This machine came with several versions of the Addendum, one a mass-printed copy with a proper glossy stapled cover (C301421-001 Rev. A) and the rest all stapled looseleaf photocopies of dot matrix masters (another Rev. A, two copies of C301421-001 Rev. B, and one copy of an even later C301723-001 Rev. A). The original ‘421 Revision A addendum dates from 1989 but the rest are from 1990. Strangely, on page “one” (page 4 or 5 if you’re counting sides) of the later addenda they read “[a]n Owner’s Manual for Stacy is currently being produced. You can obtain a copy of the manual as soon as it is printed by filling in the form at the end of this addendum and mailing it to Atari.” There is an obvious cut page in the ‘723 Rev. B where this form was snipped out and presumably sent but if they got their revised manual it isn’t here. The ‘723 is also notable for completely lacking any graphics, even Atari fuji logos (only placeholder literal text “[fuji]” appears on the copyright page). Only the later revisions mention you can warmboot the machine with Ctrl-Alt-Del or coldboot it with Ctrl-Alt-Right Shift-Del (this Stacy responds properly to both), and the later revisions have long sections dedicated to the internal hard disk that are completely absent from the ‘421 Rev. A. Best guess is that the original ‘421 was for the initial floppy-only version, and the others produced as updates for the hard disk configurations, even though those machines got FCC clearance earlier.

Stacys are limited to monochrome 640×400 hi-res on the built-in LCD, which is blue on white. The original Epson panels are notorious for their failure-prone backlights, but I was fortunate in that the prior owner had already replaced it with a brand-new substitute and done the replacement wiring. I’ve kept the new screen’s protective plastic on for the purposes of this upgrade. The spring-loaded panel next to the screen has a trackball divot that applies a light immobilizing pressure to it when the lid is closed (but also makes a handy clip when it’s open).

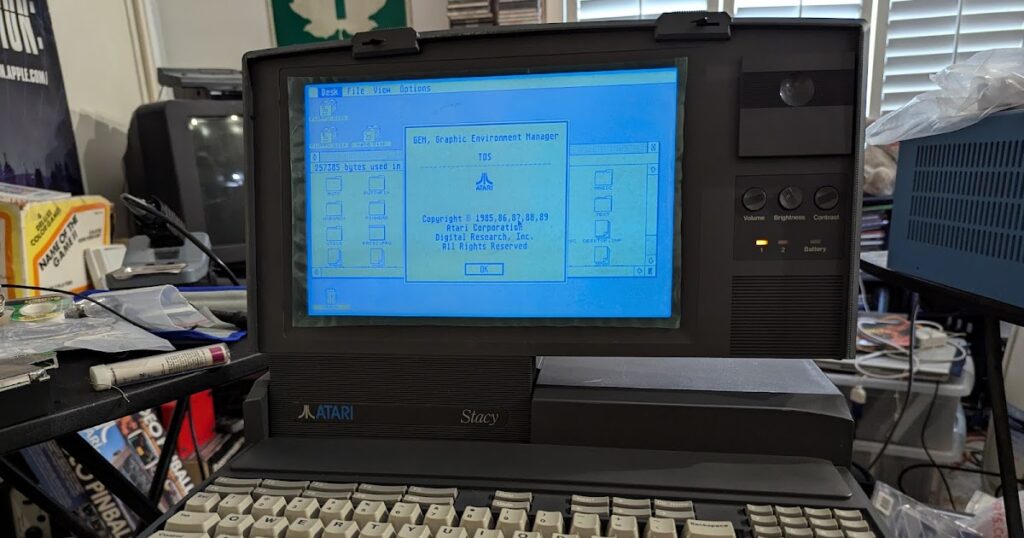

The Stacy shipped with Rainbow TOS 1.04 in 192K of ROM, newly introduced with the Stacy and provided as an upgrade for the original Megas, 520ST and 1040ST. Like all STs TOS uses Digital Research’s GEM and, underlying it, GEMDOS. 1.04 provided many bug fixes and a new file selector, and a DOS-compatible (or at least more compatible) disk format, but also introduced a small yet noticeable number of incompatibilities with older software. The “Rainbow” name comes from the rainbow Fuji logo that appears in this about-dialogue when using one of the colour lower resolution modes, but those video modes can’t be displayed on the LCD.

Keyboard and trackball. The narrow keys aren’t that great or particularly easy to hit, but the main keyboard has a decent-enough feel. Functionally it has every key that a normal ST keyboard would have with a couple in different places. The trackball also fully replaces the standard ST two-button mouse.

The battery compartment with the cover off. There is no battery hardware in this unit, as is the case for most Stacys, though you can see where the batteries would have gone. Some very early units did have the hardware and a functioning battery light, and for the rest at least one third party upgrade provided an installable internal battery option which could last up to two hours.

Rear ports, in order: RS-232 serial “modem” port, parallel “printer” port (though missing some signals on PC parallel ports), external floppy port, ACSI (not SCSI) “hard disk” DMA port, monitor connector (we’ll come back to this), MIDI out and in, and the power barrel jack. A reset button is next to it. ACSI (“Atari Computer Systems Interface”) predates SCSI-1’s standardization in 1986 but is still quite similar, using a smaller 19-pin port, a related but incompatible protocol, and a fixed bus relationship where the computer is always in control. It is nevertheless enough like SCSI that many SCSI devices can be interfaced to it — we’ll come back to this too.

The rear ports should be covered by a door, but it’s missing from this system.

The side ports are for joysticks (Atari, natch) or an Atari ST mouse. However, to have an external mouse substitute for the trackball, the switch next to its port needs to be flipped because the trackball shares the same port internally. There should be a door over these too.

On the other side is an Atari ST cartridge port — also missing its door — and the only remaining ports door on this unit, covering the expansion slot. You can infer from the fact this door is present that the expansion slot never got used by its prior owner(s), and I don’t have anything to connect to it either.

This Stacy is tagged as model LST-1124, indicating it originally came with a 20MB hard disk. The first digit is the factory RAM in megabytes, the second is the number of floppy drives, the third is the number of tens of megabytes in the included hard disk, and the fourth is always “4”. If the second digit is two, then the third digit is necessarily zero because there’d be no space for an internal hard disk in a two-floppy unit. The highest-specced Stacy would thus either be the LST-4144 (40MB hard disk, 4MB of RAM) or LST-4204 (two floppies, 4MB of RAM), depending on if you want a hard drive or not.

The Conner hard disks in these units were remarkably failure-prone as well and some can even emit a rather evil goo. A few years ago I killed my first Stacy, a Stacy2, when I opened it to extract its own failed drive. Unfortunately I managed to misalign the unkeyed Stacy power board while putting it back together and ended up putting 12V on the 5V line, letting out the magic smoke instantly. On this unit the prior owner simply removed the hard disk entirely and replaced it with a SCSI2SD. How can you get an internal SCSI drive in the ACSI-based Stacy, you might ask? Again, stay tuned.

The serial number on this 1MB Stacy appears relatively low, but I see no evidence that it’s pre-production or special in any other respect.

I have two power supplies for this Stacy, the original Atari brick (labeled “STACEY” [sic], part number C103530-002) and a replacement third-party wallwart. Although the label on the bottom of the Stacy case says it requires 18V at 2.0A, neither supply provides this: the Atari brick puts out 16.5V at 2.5A, and the wallwart 15V at 1.5A. Since the wallwart is the lowest voltage, I tend to use that one. The connector is a typical 5.5mm barrel jack but tip negative.

Anyway, let’s get this over with.

The first step of disassembly is to peel the “Stacy” applique off the front display. (Helpfully, the prior owner left it slightly offset so I could get a spudger under it, as if they anticipated this machine would be troublesome again.) This reveals two screws which attach the back cover of the display to the front.

After removing those screws, we then use a nylon spudger to wedge open the snaps holding the back display cover on.

These snaps are all around the display.

There are two more snaps on the back. With those freed, the back display cover comes off.

Turn the machine over (I put down the display cover so it could sit in it), remove the bottom doors over the ROM and memory, and then remove the case screws (three screws in front and two in the middle).

Two more screws are on the rear. These screw into a very springy steel endoskeleton which likes to move around, making it much harder to screw back into than pull screws out of, by the way. This endoskeleton will also become critical later.

Now more snaps, one on one side …

… two in front …

… and another on the other.

Now for the worst part. Somehow or another you’re going to have to get the top shell around the floppy drive and free of the keyboard. The best way I could find was to lift it up and slightly to the side, wiggling gently but constantly to get things loosened up. Resist the urge to lever around the floppy eject button with something because all you’ll likely do is just snap that piece off.

Unfortunately there is a long screw race inside on the bottom of the top case that can also be snapped off, and on my machine was already half-fractured. We’re going to have to reattach it before we put the Stacy back together, which we’ll do just prior to reassembly.

The approximately desired end result is here. Notice that the bevel of the floppy drive fits within the top case’s cross-shaped aperture — this is probably the hardest part to separate — and the floppy eject button also has its own opening. The prior owner thought ahead with the SCSI2SD, by the way: both its SD card slot and USB port are exposed with their own holes, so you can just sling SD cards to change or replace the system without cracking the case. Nicely done.

The keyboard attaches to a board on the bottom with a ribbon cable which is easily removed. This board will be very important very soon.

You can then fish out the stiffener bar the keyboard abuts. Yes, the bar is not attached to anything at this point.

This leaves a sheet metal plate covering the electronics in the bottom case. This plate is in fact what I referred to as the “endoskeleton” earlier, and I strongly suspect this plate was a requirement for FCC clearance. If you haven’t already done, close the top case and pull the display wires carefully through their hole in the bottom case so you can lift up the top case completely.

The metal plate attaches to the bottom with tabs. Using a set of needle-nose pliers, straighten them out so that the plate can lift off. There are a couple back by the battery compartment …

… around the trackball …

… and a couple on the sides where the keyboard was.

With these tabs straightened out, you should be able to remove the plate. I balanced the top case on a table so that I didn’t have to disconnect the display. This reveals the daughterboard the keyboard was connected to.

In fact, this daughterboard contains not only the keyboard connector but also the TOS ROMs and, depending on the configuration, ROM SIPP connectors or soldered RAM. The doors on the bottom allow access to the ROMs for upgrades and any SIPPs. On this 1MB Stacy, there’s nothing but soldered RAM here, so short of modifying the card we’ll need a new one.

I ordered a 4MB card from a well-known Atari supplier which was offering them as new old stock. It came completely sealed in its original packaging, so we can be confident that this particular card is as Atari shipped it.

The portion of this 4MB card that faces down (towards the ROM and RAM doors) has the two TOS ROMs, several soldered-in RAM chips and a RAM SIPP, and a Hitachi HD6301V1P microcontroller with a 4MHz crystal divided down to 1MHz. We last met the 6301, a clone of the Motorola 6801, in the peripherals for the Convergent WorkSlate (the WorkSlate itself uses a Hitachi 6303). This serves as the keyboard, mouse/trackball and joystick controller with its own 4K internal ROM and 128 bytes of internal RAM.

Counting the RAM, though, we don’t have 4MB on this side. Where’s the rest of it?

It’s on the other side, covered by tape. Why is it taped? So it doesn’t short against anything! Remember, this is exactly how Atari shipped it! The keyboard connector is here as well.

This board is quite critical. Without it, the system has no RAM, no ROM and, almost trivially by comparison, no keyboard, trackball, mouse or joysticks. If it’s not connected firmly, you’ll get a blank screen.

With the mainboard exposed, we can now swap the RAM cards. There are three daughterboards on the Stacy mainboard: the power supply, this keyboard-ROM-RAM daughtercard, and a SCSI-ACSI conversion board (which Atari calls the “hard disk controller”). That’s how the Conner drive originally, and the SCSI2SD now, could be connected to the ACSI bus. The power supply partially covers up the pin headers for the display and top case, but none of these daughtercard connections are keyed, and only the SCSI-ACSI card maintains a sufficient grip on the logic board. The power supply has cardboard on the bottom to prevent it shorting anything.

Landmarks on this logic board (with a date code of 20th week 1990) include the CR2032 clock battery in the northwest corner of this picture, the Motorola CMOS 68HC000 CPU with its 8.0106125MHz clock speed divided down from the 32042.45kHz crystal north of it, two Hitachi HD6350 serial ACIAs (clones of the Motorola 6850) with one for both MIDI ports and one for signals from the keyboard controller, and the Atari C025914-38A SHIFTER video chip partially covered by the power supply board at U20. Three socketed PLCC ASICs are on the southern half; from left/west to right/east are the C025915-38A GLUE chip (for address decoding and handling interrupts and bus arbitration), the C025912-38 MMU chip (for mapping ROM and RAM into the 68K address space, supporting up to 4MB of RAM), and the C101775-001 SHADOW LCD controller. Covered up by the floppy disk-hard disk enclosure are its Yamaha YM2149F sound chip (which also manages the parallel port and RS-232 DTR/RTS), Western Digital WD1772 floppy drive controller, Motorola 68901 USART (which generates various interrupts and manages most of the RS-232 lines), and the C025913-38 DMA chip for ACSI transfers.

Third-party RAM cards for the Stacy did exist, as well as a CPU accelerator requiring desoldering of the 68HC000. This would have been a rather complex upgrade to install.

This time I checked, double-checked, triple-checked and quadruple-checked from multiple angles that the power supply board was connected correctly.

The first sign there would be trouble was that the RAM chips on the bottom weren’t clearing the aperture. I had to bend some of the chips to get it to slot in. That’s not the only thing we’ll need to do to make this all fit, and even then it was still flexing, which wasn’t making a good connection with the logic board’s pin headers.

Still, we can see on screen from the Control Panel (more a little later) that our physical top of RAM is $400000, so we have all 4MB of RAM. Careful when testing because the now-mobile power switch has exposed connectors which can short against the case. Let’s deal with the bad trackball button next.

The left button had gotten worn, both the button switch on the trackball board itself and the bottom of the plastic prong that contacts it. I don’t have a replacement for the trackball board and I was likely to make things worse attempting to desolder and put in an equivalent switch, so after some thought I decided the least damaging option would be to improve the prong’s contact with the button. I got some photo-set high strength JBWeld cyanoacrylate, carefully put a small dot on the top of the button and immediately cured it with the light before it could run anywhere. This increased the thickness of the button without impairing the ability to depress it.

The second order of business was to repair the broken screw race prong. Superglue wasn’t going to be enough for this and I mixed up some JBWeld metal-reinforced epoxy. To avoid the prong getting lengthened or plugged up I applied the JBWeld around the break instead of directly on it, using a wire coat hanger to support the prong while keeping it patent and hollow. With the leftover JBWeld I also strengthened the shafts of some of the other plastic prongs at the same time.

Now the next problem: the metal shield will no longer fit because of dat phat RAM card. You’ll notice that there is cardboard under the shield, again also to prevent anything shorting out on it.

I don’t have great tools for cutting steel, but after about an hour with an angle grinder and some snips we have a flap we can remove that does not expose the rest of the electronics on the memory daughtercard. (Cutting the cardboard under it was rather easier.)

This surgery removes a couple places where the metal tabs would have held the shield down, so I repurposed them to hold down the 4MB board instead. It was still flexing a bit but this made things a little more rigid.

It’s now time for reassembly. The next few pictures will look like the process was simple, and it was not. What’s depicted here is in fact a consolidation of multiple false starts and a whole lot of screaming.

The first part was to put the metal shield back on and bend the tabs back to hold it in position. While doing so, be careful with the display wires to get them back into their little canal because they can literally short and spark. I don’t know how this is possible but they do! You can also get the display cabling messed up enough that the Stacy will continuously beep at you when you turn it on. The only good way I found to avoid this was to pull as much play in the display wiring into the top case as possible so that the wires don’t bunch up in the bottom case.

The prior owner had marked the stiffener bar position with a Sharpie, which is important because if you get this wrong then the keyboard can tilt up under the top case and interfere with the “uneasy sandwich.” Since it’s mobile I held it down with tape, then put in the keyboard and wormed its ribbon connector back home.

Now you have to get the top case back on around the floppy drive. Fortunately our newly reinforced screw race did not snap again. We then replace all the screws and put the cover back on the display.

The first time I got it all back together, I got a black screen. There was a moment of panic that I had killed this one too, but when I got back into it I found the memory board was not making good contact with the pin headers. I tightened the metal tabs a bit more and reassembled it.

The second time, it beeped incessantly. I carefully checked the display wiring wasn’t getting pinched or shorted and tried again.

The third time, it powered up seemingly normally, but when I checked that the RAM was indeed the expected amount … I discovered it was only detecting 2MB of it. Following a minor conniption which may have been overheard by the neighbours I disassembled it back down to the mainboard again and it once again reported 4MB.

After a couple more attempts I figured out that the front three screws, which go through the memory board, can also affect its connection with the logic board. The middle one seems to be the most involved. All of this suggests Atari never meant a 1MB Stacy to be upgraded with this particular card.

I find it technically disgusting that I’m having to adjust the screw depth to get the full 4MB, but it works. Since stuff settles, I have periodically had to readjust it, but at least I haven’t needed to take it apart again.

Let’s have a few baseline screenshots using our Hall SC-VGA-2 scan converter to turn the ST’s 71.2Hz high resolution display into the 60Hz my VGA box can capture. This stack doesn’t get a pixel-perfect grab but the budget isn’t there for the super duper OSSC right now, so you’ll just have to deal.

Starting up. The Mouse Accelerator III startup tool was new for the Stacy and added trackball/mouse speed control, backlight, modem data as setting the system as not idle, and hard disk parking (irrelevant with the SCSI2SD). It can also be used with Mega STs because the Stacy is, again, basically a portable gimped Mega. The hard disk driver is an older copy of the third-party HDDRIVER that was already on the SD card.

I always liked the ST “busy” cursor — a bee. I wonder what they thought about this in Utah.

Desktop. All of this was what the previous owner left.

I’m pleased to note that the mouse button works a lot better. Doubleclicking in particular actually functions consistently for a change.

We’ll just do a quick couple tests to make sure everything is still happy.

Rainbow TOS version box.

The Atari extensible control panel, much like Macs use CDEVs, uses CPXes (Control Panel Extensions).

We’ll go to a third-party CPX called Show System. This was what I was using to display the memory configuration before.

There are many things it can be configured with and lots of information it can grab, but we’ll display the OS Variables option to see what we have under the hood.

And, now adjusted, we still have 4MB of memory to my great relief with the computer back in one uneasy piece. I’m not 100% happy with the end result but the trackball button works better and our memory has quadrupled, at least when Stacy is in a good mood. Like I say, I can only conclude that the 1MB Stacy was never meant to be upgraded in this fashion. One of the third-party RAM cards might have worked, but I have no idea where I can find one. Regardless, based on the amount of apoplexy and late-night screaming that Stacy caused over the past couple months’ weekends, my wife has told me in no uncertain terms that if I’m ever going to crack this laptop open again, I need to have a good long talk with her about it first.

I’ve decided I’m okay with that.