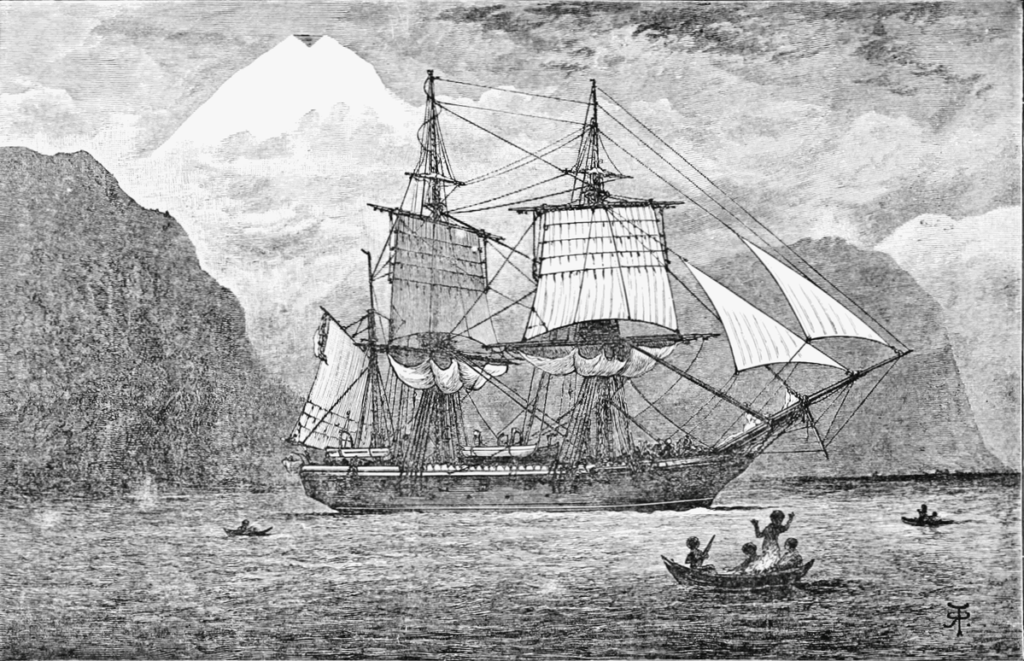

HMS Beagle sails through the Straits of Magellan

Wikimedia Commons

“After having been twice driven back by heavy southwestern gales, Her Majesty’s ship Beagle, a ten-gun brig, under the command of Captain Fitz Roy, R.N., sailed from Devonport on the 27th of December, 1831.”

So begins The Voyage of the Beagle, Charles Darwin’s account of his trip around the coast of South America, between the islands of the Galápagos, and back to England—a journey that inspired his theory of evolution by natural selection.

Darwin was a young man of 22 at the time, a recent graduate of Christ’s College, Cambridge, where his intention to become an Anglican priest had morphed into studies in botany, animal biology and geology.

In August 1831, Darwin received a letter from his mentor, fellow geologist John Stevens Henslow, explaining that the Beagle’s new captain Lieutenant Robert Fitzroy was seeking an assistant who could help with “collecting, observing, & noting anything worthy to be noted in Natural History” on an upcoming voyage.

“I have stated that I consider you to be the best qualified person I know of who is likely to undertake such a situation,” Henslow wrote.

Dawin’s father, however, took a much different view of his son’s qualifications and strongly opposed the voyage. His father wanted him to “settle down as a clergyman,” so Darwin politely declined the offer. If it were up to him, “I should I think, certainly most gladly have accepted the opportunity,” Darwin wrote back to Henslow.

Just a few days later, his father’s mind changed. Darwin hastened to accept the offer to see the watery part of the world and all its thrilling natural features. The expedition would, in Darwin’s words, “complete the survey of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego … survey the shores of Chile, Peru and of some islands in the Pacific.”

As the Beagle left England on December 27, its crew fell into a routine that would last the next five years. While others dedicated themselves to mapping and surveying work, Darwin took the role of a “gentleman naturalist,” strolling about and making geological and zoological observations.

He religiously kept a journal of his detailed notes as “not a record of facts but of my thoughts,” as he described it in a letter to his sister. He also became an avid reader of the Principles of Geology by Charles Lyell, a prominent geologist. Among other things, Lyell’s work aimed to show that small, incremental changes could have profound effects over long periods of time.

The Beagle reached the Galápagos Islands, a volcanic archipelago in the Pacific Ocean, in September 1835. As the ship hopped between the islands, Darwin “industriously collected all the animals, plants, insects & reptiles” from each, he noted in his journal.

Later, someone aboard the ship pointed out that “the tortoises differed from the different islands, and that he could with certainty tell from which islands any one was brought.” This gave the scientist the inkling that evolution could take different paths of speciation depending on an island’s unique conditions. Perhaps small changes in species over time, branching out from a single ancestor, could result in starkly unique tortoises, Darwin reasoned.

Upon the Beagle’s return to England in October 1836, the idea was still just an inkling. It would take another 23 years, including a friendship with Lyell and a retreat into English country life, until Darwin fully fleshed out his vision of evolution in the groundbreaking On the Origin of Species. Small things, after all, accumulate when given enough time.