Eggers told me Death and the Maiden was on his mind while adapting Nosferatu, as well as countless other classic tales about love being supplanted by obsession or self-annihilation, from The Daemon Lover to Wuthering Heights. They each tap into something that’s primal and appealing to the filmmaker’s Jungian leanings about how “these bits and bobs of the past are knocking around in everyone’s heads to some degree.” All of the director’s films to date operate on the idea that we culturally share a kind of subconscious in which fears, hopes, and even orgasmic relief are half-remembered and repeated.

This is never more explicit than in Nosferatu, a film in which Eggers renames his Van Helsing character after real-life Jungian psychologist Marie-Louise von Franz. In fact, it is Dafoe’s Von Franz who muses that in pagan times Ellen might have been revered as a Priestess of Isis, celebrated in the cities of Rome or Thebes, instead of dismissed and locked away as a “troubled wife” by her father, her husband, and her husband’s condescending friend who is the epitome of their 19th century moment.

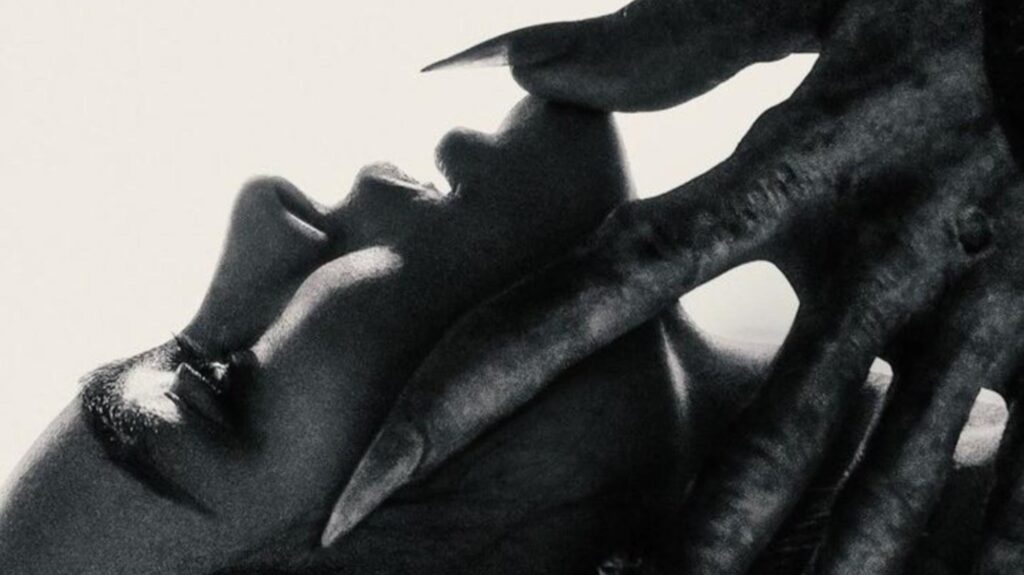

Von Franz is Eggers’ voice in the film, offering true pity but also admiration for Ellen’s plight. Unlike the literary Van Helsing, Von Franz has no delusions that he can defeat the vampire, but he knows Ellen’s feminine power can conquer the beast. For Ellen, the cost is succumbing to literal darkness. She is indeed wedding herself to Death made flesh. But she isn’t surrendering to evil; she is recognizing the darkness that is in her own nature… as we all must. She then uses it to save a husband she deeply loves, even if he can never appreciate how.

“I think that she really does love Thomas,” Depp told me. “To me that really is the love story, because she wants so badly to be what he needs and what he wants, and I think he so badly wants to be what she wants… [but] she has this side to her that he can’t understand, unfortunately, but I think is fulfilled in her pull to Orlok.”

Whereas other Dracula movies seek to turn the vampire into a romantic figure, the romance of Eggers’ Nosferatu comes from Ellen’s genuine love of Thomas. The vampire represents a different side of her nature that someone as earthly and conventional as Thomas can never fully accept, but that doesn’t mean the vampire is itself romantic. Even Orlok says he is nothing but “an appetite” in the movie. And his appetite is to destroy and consume all in his path, including something as delicate and youthful as Ellen. Her self-actualization is thus accepting that she has the urge to be destroyed. Perhaps we all do.

“There was a lot of criticism at the end of the second half of the 20th century about 19th century novelists who were mostly male, but also female, needing to kill off the heroines who had sexual desire or leanings to darkness, and how misogynist that is, which is not untrue,” Eggers mused about the motifs he is exploring. “But I think that it was also interesting [to have this] archetype of this demonic female who was the hero of the story and the savior—the cultural savior [who] the Victorians needed to somehow get out.”