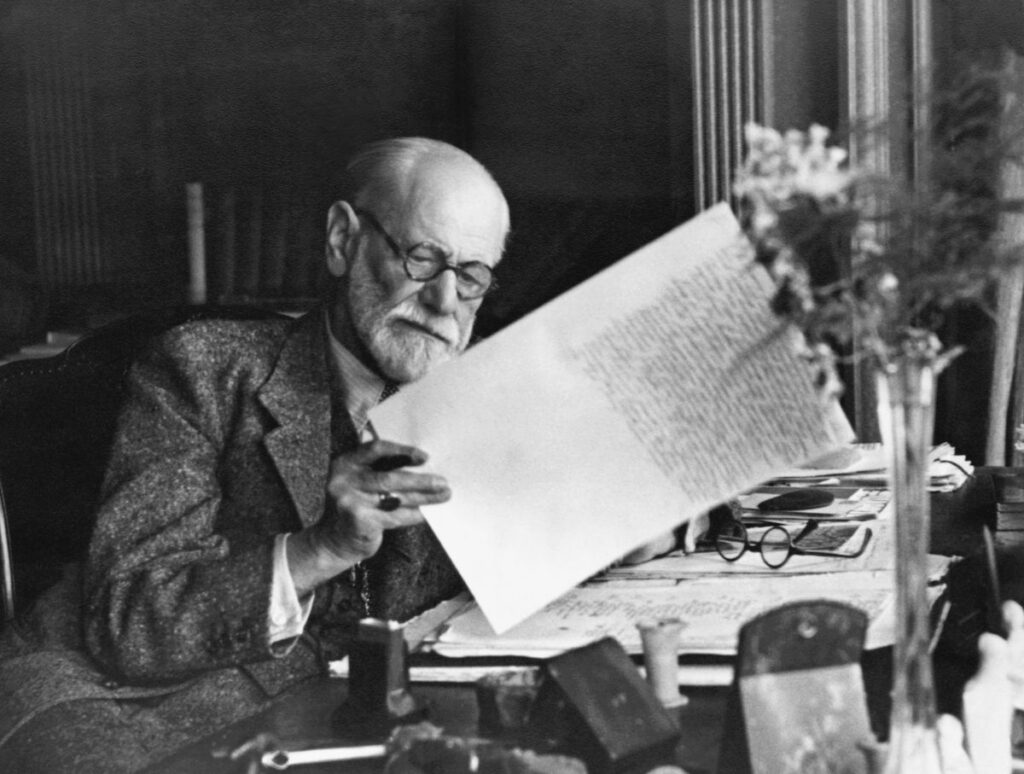

Sigmund Freud in the office of his Vienna home in 1930

Bettmann / Contributor

Women intrigued Sigmund Freud, but they also baffled him. As the founder of psychoanalysis once said, “The great question that has never been answered, and which I have not yet been able to answer, despite my 30 years of research into the feminine soul, is ‘What does a woman want?’”

Freud learned a lot from the women around him, including his patients, his peers and his daughters. Now, 85 years after the Austrian neurologist’s death, a new exhibition at London’s Freud Museum explores his complicated relationship with women.

“Women & Freud: Patients, Pioneers, Artists” fills the entire museum, which was Freud’s last home and workplace. It incorporates historic artifacts—such as manuscripts, letters, photos, objects, diaries and film footage—as well as contemporary works by women artists. The exhibition also explores the history of the Hogarth Press, which began publishing Freud’s work 100 years ago.

The neurologist famously developed many controversial—and often incorrect or misogynistic—theories about women during his lifetime. The exhibition aims to present this part of Freud’s work in a new light, arguing that it may have inadvertently advanced the feminist revolutions that came later.

“Did the talking cure give women the power to speak in their own voice?” writes the museum on the exhibition website. “Did Freud raise women’s private, secret thoughts and emotions into a public (and ‘scientific’) discourse so that they could consider their own sexuality openly, even if in argument with him? Where does sexual difference elide into gendered expectations or prohibitions? These are some of the questions the exhibition raises through its women.”

The show is the first to celebrate the women in Freud’s world, according to the Art Newspaper’s Maev Kennedy. Many of his patients went on to become successful psychoanalysts themselves. The exhibition explores women’s professional contributions not just to the fields of child psychology and child development, but to the “very tenets of psychoanalysis,” Michael Marder, the author of a forthcoming book on Freud, tells the Observer’s Vanessa Thorpe.

An entire room of the museum is dedicated to Anna Freud, Freud’s youngest daughter, who went on to become a pioneering psychoanalyst in her own right. The exhibition also celebrates Melanie Klein, Juliet Mitchell, Julia Kristeva, Helene Deutsch and Marie Bonaparte.

Bonaparte was Napoleon’s great-grandniece, and she helped Freud, who was Jewish, escape the Nazis in 1938. “Despite the outsized role ‘the last Bonaparte’ played in the history of psychoanalysis, too few are aware of her significant contributions,” according to the museum.

The artworks featured in the exhibition include spreads from Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir Are You My Mother? and Paula Rego’s cloth “dollies.” Also on view is Sarah Lucas’ SEX BOMB, a concrete and bronze sculpture of a stiletto-clad figure slumped over in a chair.

“The exhibition’s effort to recast the story of Freud’s relationship to women in a positive light—indeed the relation of psychoanalysis to femininity—is laudable,” writes Simon Wortham, a scholar of literature and philosophy at Kingston University in London, in the Conversation. “However, it is left to art to retell this tale through more disturbing interventions.”

“Women & Freud: Patients, Pioneers, Artists” is on view at the Freud Museum in London through May 5, 2025.