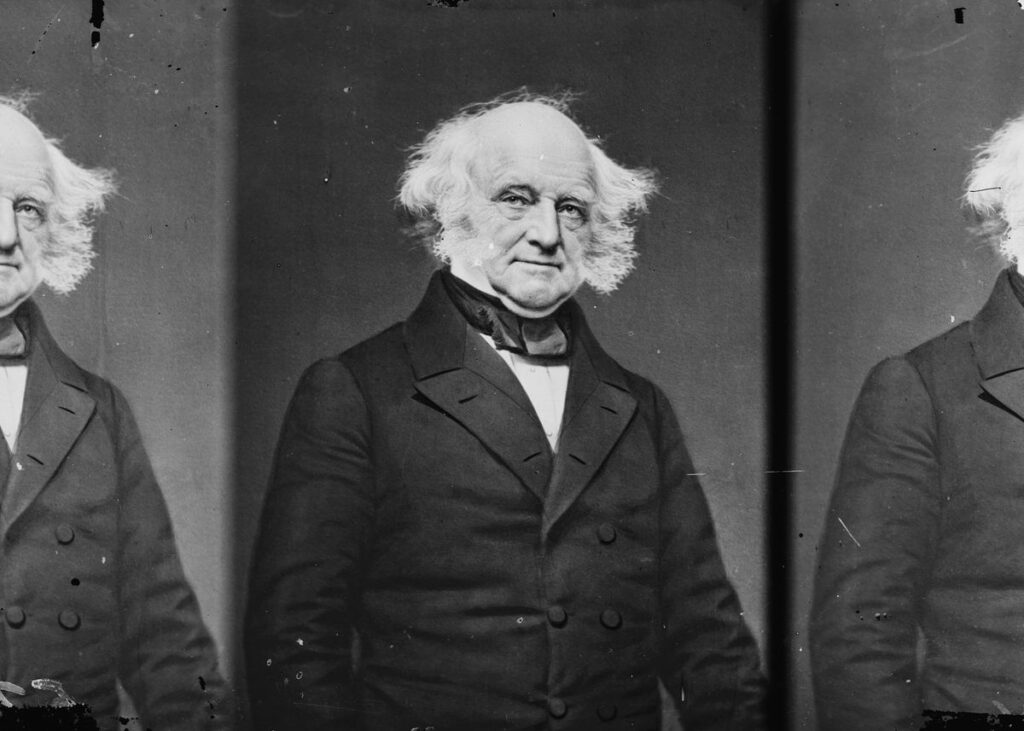

Martin Van Buren in 1860.

Library of Congress

When Martin Van Buren arrived in Washington to be sworn in as a senator in 1821, he told a friend he planned to “build up a party” for himself. It was an odd time to be party-mongering, and Van Buren an unlikely party-monger. Republican James Monroe had run unopposed in the 1820 presidential election, and “every politician in Washington, with varying degrees of enthusiasm … was calling himself a Republican,” writes James M. Bradley in Martin Van Buren: America’s First Politician, a lively and illuminating new biography of our eighth president—the first to be born a U.S. citizen. Absent a strong opposition party, Van Buren lamented that politicians were appealing less to ideals and more to personalities, and wished, as he put it in an 1827 letter, to unite citizens through “party principle,” rather than “personal preference.”

Born in 1782 to a tavern-keeping family in Kinderhook, New York, Van Buren had little schooling but made himself a lawyer, rising to the heights of power despite his lack of military experience or strong family ties to ensure patronage. At 5-foot-6, he was considered notably short, and friends and foes called him the “little magician” for his outsize political talents. He proceeded swiftly from senator to secretary of state, vice president and president. And though he failed to win a second term, Bradley says, “He built and designed the party system that defined how politics was practiced and power wielded in the United States.” We are living in the world Van Buren created.

In the first decades of the Republic, leaders had generally called themselves Federalists or Republicans, but “few imagined that parties would be a permanent feature of the nation’s political life,” Bradley writes. “They expected parties to disband once the Republic was more secure and its great issues settled.” Van Buren plowed ahead, with the thoroughly modern view that parties were not a regrettable necessity but a revolutionary means of achieving and using power. With Andrew Jackson, he co-founded the Democratic Party in 1828, cannily banking on Jackson’s personal appeal to win that year’s election; Van Buren became Jackson’s vice president, and the Democrats dominated politics until 1860. “He didn’t think that politics should be a hobby for gentlemen to practice in their spare time,” Bradley says. “A party had to have an organization, a structure, a personality, and it should be run by professionals.”

As early as 1819, Van Buren had called slavery “a moral evil,” but he appeased its partisans frequently. “There was a dark side to Van Buren’s ascendancy,” Bradley writes. “The Democratic Party became a vehicle for the expansion of slavery, the forced expulsion and dispossession of Native peoples from the eastern United States, and imperial conquest of the West.” Indeed, Van Buren helped professionalize the use of race “in different and effective ways as a wedge issue in elections and political debates,” Bradley says. “These practices are still very prevalent today.” The main difference? “Van Buren never could have conceived of a party system where big money plays such an enormous role.” Still, Bradley says, “in many ways,” today’s politicians “are using [Van Buren’s] playbook.”