In this week’s story, “The Leper,” the narrator discovers that his father has confessed to spying for North Korea and is under arrest in Seoul. How did this premise come to you? When was the story first published in its original Korean version?

This story is based on a real incident involving my father that occurred in the mid-nineteen-eighties, when the military regime of Chun Doo-hwan was at its height. But it was not published in a literary magazine until 1988, after some measure of democratization had been achieved. However, depicting a person who claimed to be a spy for North Korea was still a sensitive issue that touched on major taboos in Korean society at the time, so I had to write it with some discretion.

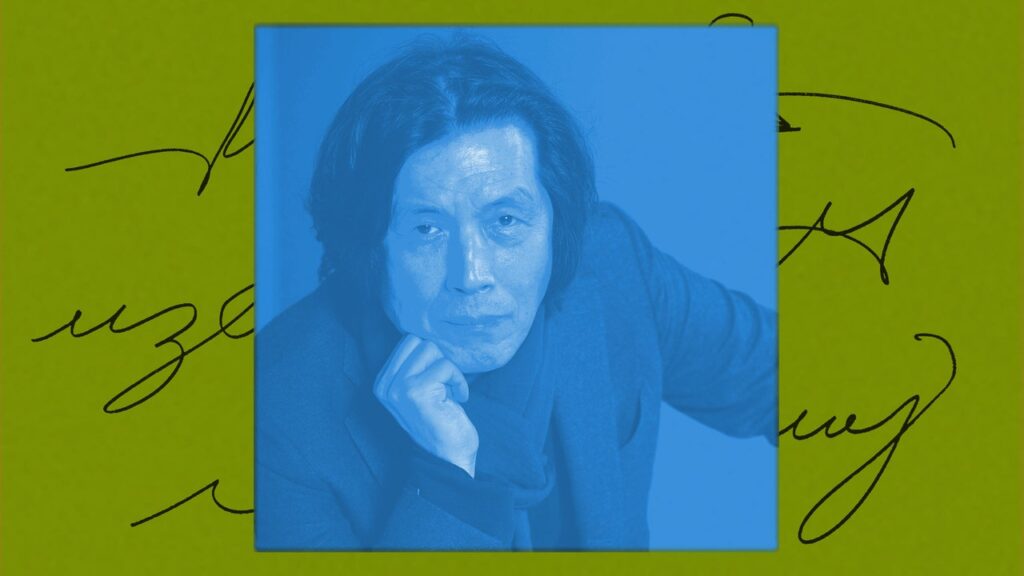

The story, which has been translated by Heinz Insu Fenkl, appears in your forthcoming collection, “Snowy Day and Other Stories,” translated by Fenkl and Yoosup Chang. It will be published by Penguin Press in February. In what period of your life were you writing these stories? How do you feel about them going out into the world again, this time in English?

I wrote this story at a time when fundamental changes were taking place in Korean society. The military dictatorship that had ruled for decades was falling, democratization was occurring, and the Seoul Olympics were being held, so the tenor of the whole society was changing. I was in my mid-thirties then, and I felt that I needed a change. As a writer, I was feeling the limits of my abilities and was thirsty for a new way of communicating. And I think that thirst is what led me to the film industry. Now the stories I wrote back then are meeting new readers in English, across the vast span of thirty or forty years. And I’m thankful for this amazing opportunity that I would never have imagined when I wrote this story.

In “The Leper,” we learn that the narrator’s father was a Communist who’d once been active in the old South Korean Labor Party. Was it dangerous to hold those kinds of beliefs in South Korea in the years after the Korean War?

After the Korean War, the dictatorship suppressed those who participated in the human-rights and labor movements, or who called for democracy, by labelling them as Communists. But there were virtually no cases of those people actually being Communists. If someone had revealed that they were a Communist, they would have been ostracized like a leper—like the father in the story—subject to legal sanctions, and isolated from society. The situation is not much different now.

Was the fear of North Korean infiltration and espionage omnipresent up until the nineteen-eighties? Between 1961 and 1988, the country had periods of rule by military dictatorship. Did this have any impact on what you could write and publish?

Even after the Korean War, North Korea continued military provocations and made serious attacks on the South. But the real fear that those incidents created was no less than what was instigated by the military dictatorship in South Korea. The South Korean military regime justified its violence toward its own citizens by using the threat of North Korea as a rationale. In the Gwangju Uprising, hundreds upon hundreds of citizens were massacred by the military, which had seized power through a coup in 1980. I was a writer who believed in William Faulkner’s idea that literature should be for the souls of the suffering people—“the problem of the human heart in conflict with itself”—but in the face of the regime’s violence, my words felt less powerful than a single line of a slogan at a protest. What role could my writing play in changing reality? While I was constantly asking myself these questions, I still had to write so as not to deny reality. The stories included in the “Snowy Day” collection were written amid these questions about the role of literature and how to communicate with readers.

The father’s life has amounted to nothing. His wife, the narrator’s mother, worked and kept the family going until her death. Has the narrator tried to mold himself in opposition to his father? Has that distorted the trajectory of his adult life?

This story reflects my actual relationship with my father, to some extent. It also shows how our generation, born after the Korean War, clashed with our fathers’ generation, who experienced colonialism and war firsthand. In the case of Koreans, due to the history of repeated upheavals since the beginning of the twentieth century, generational conflicts are complex, internalized, and often violent. Personally, I tried to live a different life from my father, and even tried to change the personality I inherited from him (passionate and impatient), and I can say that I was somewhat successful in that regard.

In “The Leper,” we learn that the narrator goes by the name Kim Youngjin, but that his given name as a child was “Maksu.” He hated the name when he was a boy, but didn’t learn why his father had named him as a tribute to Karl Marx until he was older. Can you imagine him ever changing his mind about that name? Does he think of himself as Youngjin or Maksu?

For Koreans at that time (and to some extent even now), Karl Marx was not just a historical figure but a kind of demonic being symbolizing the world of darkness. So, to the protagonist, the name “Maksu” must have felt like a curse that his father had placed on him. Perhaps if he could have better understood his father, that could have been a decisive turning point in the story, but it would not have been easy for him to change his mind about that name—at least as long as he lived in South Korea. In any case, his confusion about identity would have been inevitable, given his two names. This is not only true of the protagonist. Many Koreans experience an internal division amid the continuing conflict between the South and the North.

[TRANSLATOR’S NOTE: To a Korean, the narrator’s surname, “Kim” (the same as Kim Il-sung’s, the ruler of North Korea at the time), when juxtaposed with the demonized “Marx,” would link him even more intensely with the idea of communism.]