Kyle Abraham is one of today’s most sought-after choreographers. He has been on the downtown contemporary-dance scene for more than two decades, and in 2006 he founded his own company, A.I.M by Kyle Abraham (the initials stand for Abraham in Motion), focussing on Black and queer culture. Abraham’s career took off, with international tours and commissions from major companies; in 2018, he brought the music of Kanye West into the sanctum of New York City Ballet. The dances I’ve seen are always accomplished and full of ideas, but now he has done something truly extraordinary: “Dear Lord, Make Me Beautiful,” which had its world première recently at the Park Avenue Armory, is a deeply personal portrait of his depressed inner state, set against the splendor of the world around him. He made it for himself and sixteen dancers, mostly from A.I.M, and it marks his return to dancing in this ensemble.

In the program notes, Abraham, who is forty-seven, writes about aging, the fragility of memory, and his father’s early-onset dementia. He began work on the dance in 2021, and he laments the “chaos of pandemic debris”; he also references the environmental crisis, Octavia Butler’s “apocalyptic narrative of Black American Futures,” and his own “fading hope and prayer” for change. These are thoughts. Yet the work he has made has no narrative and no familiar gestures. It is a fully abstract dance that, like nature and aging, works organically, seeping into us through skin and eyes and ears. And it is a beauty.

Inside the cavernous hall of the Armory, I found myself enveloped in an intimate and enchanted space at its center, demarcated by a dappled green forest, a continuously morphing digital backdrop (designed by the artist Cao Yuxi, with light by Dan Scully) that spread like a lush carpet across the stage floor, to our feet. The musicians of the chamber ensemble yMusic, who composed the original score in collaboration with Abraham, sat high on a platform to the left. As they played a soft, reedy sound, Abraham ran into the green wilderness wearing a loose white speckled costume (by Karen Young), which seemed to change colors in synchrony with the ever-shifting backdrop. He kept running, circling the large stage several times with an easy gait, occasionally flipping backward with a light kick at the past, then resuming his forward pace. At times, he slowed; his posture changed, the shoulders giving slightly, the gaze lowered, and we saw the unencumbered run of youth give way to the weight and thought of age. Finally, he stopped, his back to us, standing on one leg, arms raised to the immensity of green, before eventually disappearing into the wings.

For the next hour, Abraham and his troupe performed a kind of dance memoir that unfolded in finely wrought patterns. The dancers seemed close and unified, with shared habits gained over months of moving together. There were duets, solos, trios, groups. The theme of running recurred, as did moments of isolation, with Abraham appearing preoccupied and diminished, unable to fully participate as the others moved around him. We sensed his vulnerability from within, as if his mind’s eye could see only his own invisibly faltering insides. This was subtly done. His body is still very much whole; his being is not.

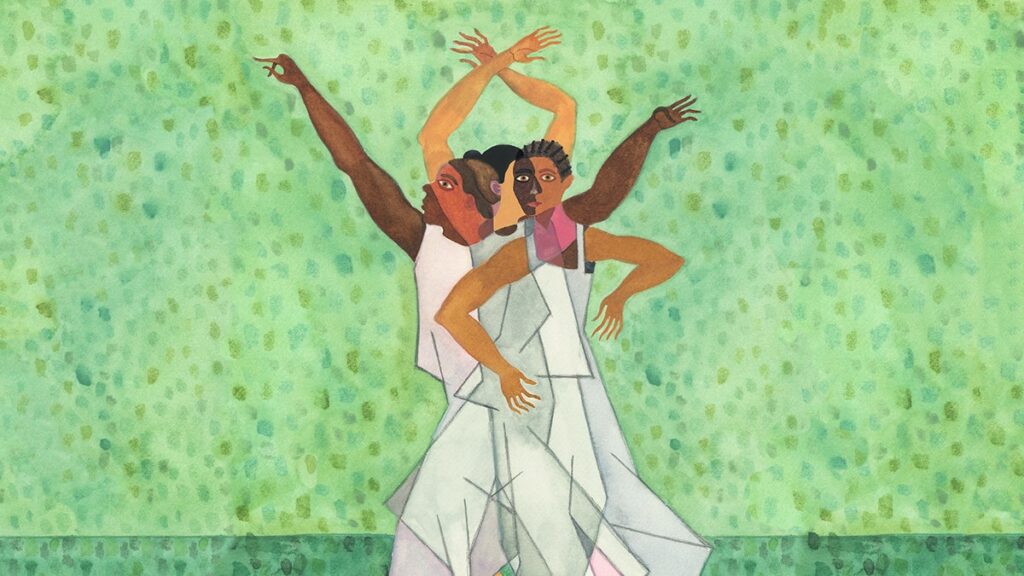

Abraham’s performers, meanwhile, offer an intimate and flowing dance that seems as natural to them as water and air: sweeping movements, elegant and fluid line, with an intense physical focus on the inner life. They are a diverse group—Black, Asian, white—but there is no hint of performative identity. They seem to come from nowhere and everywhere at the same time: we might trace their vocabulary to Bill T. Jones (with whom Abraham has danced), or back to José Limón and other modern and postmodern dancers, or to ballet, or street and club dancing, but, whatever the influences, the dance has the unself-conscious ease of a fully integrated and naturalized form. It is worth stopping for a moment to appreciate just how difficult this is to achieve. Influences have a way of appearing, like family traits, in idiosyncratic details such as the turn of a head or position of a hand, but here the steps and styles have been stripped of attitude and etiquette, to their elemental forms. The discipline is physical, but also mental and emotional, and it is achieved by an interiority that seems to leave the materiality of everyday life behind.

One way we see this is in their range: these are terrific dancers who can occupy both the earth and the air at the same time. Most dance techniques privilege one or the other, because weight is so difficult to master. Dancers trained in ballet spend years aiming for the sky, and their bodies do not easily fold to the ground, whereas many modern dancers practice falling until it is second nature; the earth is their habitat. Abraham’s dancers can sink down through the knees into the floor and in the next breath push up into lightness and flight, without making a show of it. Take Amari Frazier, an extraordinarily sensitive performer of almost androgynous qualities. His movement seems to happen to him, as if it were rising from within or coming from some mysterious outside source. We watch the consequences, for example, as a quick sharpness passes through his inner torso, or as he absorbs a gesture into his smooth carriage and the wide lunging walks that structure his dance. I was reminded of how emotions and memories can physically embed themselves in us, and how their release can move like a small storm through the body. Frazier notices and directs this storm, as if psychology were physical.

There were moments when the flow of the dance slipped, surprisingly, into cliché—for instance, when the dancers gathered at the back of the stage, two women hugged each other and we felt that perhaps someone had died. Abraham stood aside, unable to feel, and the music wound itself into a compulsive free-jazz-like cacophony. The scene made words like “community” and “empathy” rush to mind, disrupting fragile and abstracted interiority with something more instructional and sentimental. Yet the moment felt more protective than manipulative, almost like a closing of ranks after too much had been exposed. It was only later that I realized a strange reversal was occurring: the highly crafted beauty of the stage world—dancers, set, sound—was taking on the oppressive and restricted character of Abraham’s own mind. There was little place in this dance for eruptions of human temperament. Beauty can be a refuge, but it can also be a harbor for depression.

Abraham’s depression, I sensed, was shading into melancholia, a group sadness with no individual remedy. The vividly colored backdrop and stage dissolved to white; pattern, the organizing principle of the bodies and of the world that Abraham had so carefully constructed, was gone. Then the dancers disappeared, too, except for Abraham and a couple, who separated and lapped the stage one last time before leaving. Abraham was alone, drenched in white and walking, as small shudders passed through his body. His pace slowed until he was walking in place, and, as the lights went dark, a bright spot picked him up for a moment, and then went black.

I did not fully believe this too literal final image, which seemed to evoke the peace of eternal white in an otherwise devastating portrait of despair. Or was it ambivalence, a resort to truism when nothing else seems possible? By making a dance so personal and whole, grounded in nothing but itself, Abraham reminds us that abstraction, which we sometimes think of as coldly formal and detached, can also be a language of loss—an impulse to purify and isolate art from violence and feelings too overwhelming to express. Even the prayerful title, “Dear Lord, Make Me Beautiful,” contains a cry of anguished doubt about what is to come—will you make me beautiful?—and points us to the problem of endings. The future is hard to mourn. ♦