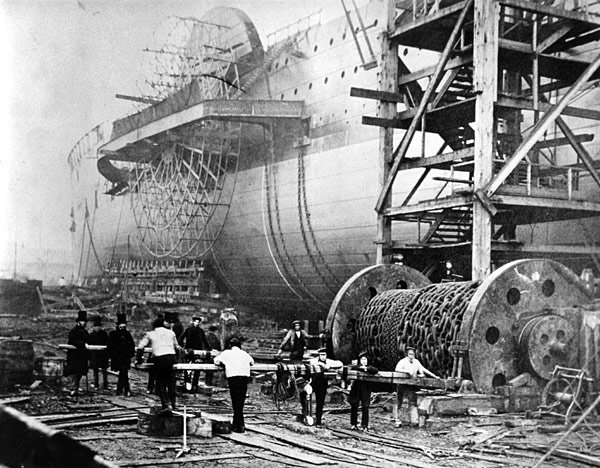

The ship the SS Great Eastern in 1858.

Early Life and Education

Brunel was born on the 9th of April, 1806, in Portsmouth, England, to a French father, Marc Isambard Brunel, and an English mother, Sophia Kingdom. Marc Brunel was an accomplished engineer in his own right, working on various mechanical and civil engineering projects in Britain. From an early age, Isambard was exposed to the world of engineering, with his father encouraging his intellectual curiosity and fostering his talents.

Brunel was educated at prestigious institutions in England and France, where he developed a strong foundation in mathematics, mechanics, and engineering principles. His formal education began at the Henri-Quatre School in Paris and continued at Lycée Saint-Louis before he returned to England. He then apprenticed under his father, gaining practical experience and learning firsthand from an expert engineer. This mentorship would lay the groundwork for his illustrious career, and the pair would collaborate on several major projects.

The Thames Tunnel: A Landmark Feat of Engineering

One of the earliest and most significant projects that shaped Brunel’s career was the Thames Tunnel, which he worked on alongside his father. Started in 1825, this tunnel was the first to be successfully constructed under a navigable river, connecting Rotherhithe and Wapping in London. It was an ambitious project fraught with challenges, including financial troubles, technical difficulties, and hazardous working conditions.

Brunel took on a leadership role as the chief assistant engineer, displaying his characteristic resourcefulness. He helped develop innovative techniques, such as the use of a tunnelling shield—a safety structure that allowed workers to dig safely through the riverbed without the tunnel collapsing. The tunnel itself was considered a marvel of engineering at the time, overcoming immense pressures and the threat of constant flooding.

Though the Thames Tunnel was beset by numerous setbacks and took nearly two decades to complete, its successful opening in 1843 was used only for pedestrian traffic until the 1860s, when it was converted to railway use.

The Thames Tunnel solidified Brunel’s reputation as a rising star in civil engineering. The tunnel remains in use today as part of the London rail network, a testament to its durability and Brunel’s engineering vision.

The Great Western Railway: Revolutionizing Transportation

Brunel’s most famous and far-reaching contributions came in the realm of railway engineering. In 1833, before the Thames tunnel was complete, at just 27 years old, he was appointed chief engineer of the Great Western Railway (GWR), a project that would cement his legacy. His vision was to create a seamless rail connection between London and Bristol, facilitating the movement of goods and passengers across the country with unprecedented speed and efficiency.

Brunel’s design for the GWR was innovative in multiple ways, but one of his most notable decisions was to use a broad gauge of 7 feet, rather than the standard gauge of 4 feet 8½ inches. He believed the wider gauge would allow for greater stability, faster speeds, and a more comfortable ride for passengers. While the broad gauge did offer some advantages, it was ultimately phased out in favor of the standard gauge, due to the logistical complications of operating different rail systems across the country.

Nevertheless, Brunel’s work on the GWR was groundbreaking.

His commitment to high-quality engineering was evident in the construction of viaducts, tunnels, and stations, all designed with precision and an eye for aesthetics. Two of the most famous structures built for the GWR are the Box Tunnel and Maidenhead Railway Bridge.

The Box Tunnel, completed in 1841, was the longest railway tunnel in the world at the time, stretching 1.83 miles, (approximately 2.95 kilometers), through the chalk hills of Wiltshire. It was an extraordinary feat of engineering, requiring meticulous planning and execution. Legend has it that Brunel aligned the tunnel’s construction so that on his birthday, the 9th of April the sunlight would shine straight through from end to end.

Earlier the Maidenhead Railway Bridge, with its flat, wide arches, was another testament to Brunel’s brilliance. Completed in 1838, it was revolutionary in its use of low-rise arches that allowed for a stable railway crossing without compromising the integrity of the structure. Today, the bridge remains in use, another symbol of Brunel’s lasting contributions to British infrastructure.

The Clifton Suspension Bridge: A Masterpiece of Design

One of Brunel’s most iconic works, the Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol, stands as a symbol of his bold engineering vision. While the bridge wasn’t completed during his lifetime, Brunel began work on it in the early 1830s after winning a design competition. His daring design called for a suspension bridge spanning the Avon Gorge, with a total length of 234 yards, (214 meters).

The construction of the bridge faced numerous financial and technical difficulties, however, it was eventually completed in 1864, five years after Brunel’s death. Needless to say, the Clifton Suspension Bridge has since become an enduring symbol of British engineering, celebrated for both its functional design and its graceful beauty. The bridge, still in use today, is often seen as a testament to Brunel’s ingenuity and his ambition to create structures that were as visually stunning as they were practical.

Engineering the Seas: Brunel’s Ships

Brunel’s talents were not limited to land-based engineering. His foray into maritime engineering led to the construction of three revolutionary ships that would set new standards in shipbuilding and sea travel.

SS Great Western (completed 1838): This was Brunel’s first foray into shipbuilding and the world’s first steamship designed for transatlantic service. The Great Western was a wooden paddle steamer, which was considered the largest passenger ship of its time. It successfully made the journey from Bristol to New York in 15 days, marking the beginning of regular steam-powered transatlantic crossings. The ship’s success proved that steam-powered vessels could dominate long-distance sea travel.

SS Great Britain (completed 1845): Brunel continued to push the boundaries of maritime engineering with the SS Great Britain, the first ocean-going ship to be built with an iron hull and driven by a screw propeller. At 322 feet long, (just over 98 meters), it was the largest ship afloat at the time. The SS Great Britain combined the best of both worlds, using both sails and steam power and set a new benchmark for ship design. It revolutionized shipbuilding, influencing the design of future iron and steel ships.

SS Great Eastern (completed 1859): Brunel’s most ambitious and controversial ship was the SS Great Eastern, intended to be the largest ship in the world and capable of carrying 4,000 passengers. It was an extraordinary engineering feat—692 feet long, (almost 211 meters), and 18,915 tons, (over 19218 metric tons). Unfortunately, the Great Eastern was plagued by mismanagement, cost overruns, and technical difficulties, making it a commercial failure. However, its design innovations, particularly in terms of double hull construction, had a lasting impact on shipbuilding practices.

Lasting Contributions and Legacy

Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s career was marked by audacity, innovation, and an insatiable desire to push the limits of what was possible in engineering. His work on railways, bridges, tunnels, and ships not only transformed Britain’s infrastructure but also laid the foundation for modern engineering practices.

Brunel’s achievements extended beyond the technical. His vision of an interconnected Britain, where goods and people could move quickly and efficiently across the country and beyond, helped drive the Industrial Revolution and fostered economic growth. His pioneering use of materials such as iron, his development of new construction techniques, and his application of steam power to transport set new standards for engineering that would influence future generations of engineers.

While not all of his projects were commercial successes, Brunel’s contributions to society are undeniable. His work on the Great Western Railway alone reshaped the British economy and transformed cities such as Bristol, which became key industrial hubs. Brunel’s bridges, tunnels, and ships remain iconic landmarks, serving as testaments to his genius and the transformative power of engineering, in addition, to interconnecting travel.

In recognition of his extraordinary contributions, Brunel was honored in his lifetime and continues to be celebrated posthumously. In 2002, he was named second in a BBC poll of the 100 Greatest Britons, a fitting tribute to the man whose work helped build the modern world.

In conclusion, Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s life and career were defined by an unwavering commitment to innovation and a drive to overcome engineering challenges. From the Thames Tunnel to the Great Western Railway, the Clifton Suspension Bridge, and his revolutionary ships, Brunel’s work touched nearly every aspect of transportation in the 19th century. His inventions and achievements not only reshaped the physical landscape of Britain but also left an indelible mark on the history of engineering, making him a true visionary whose legacy continues to inspire.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.