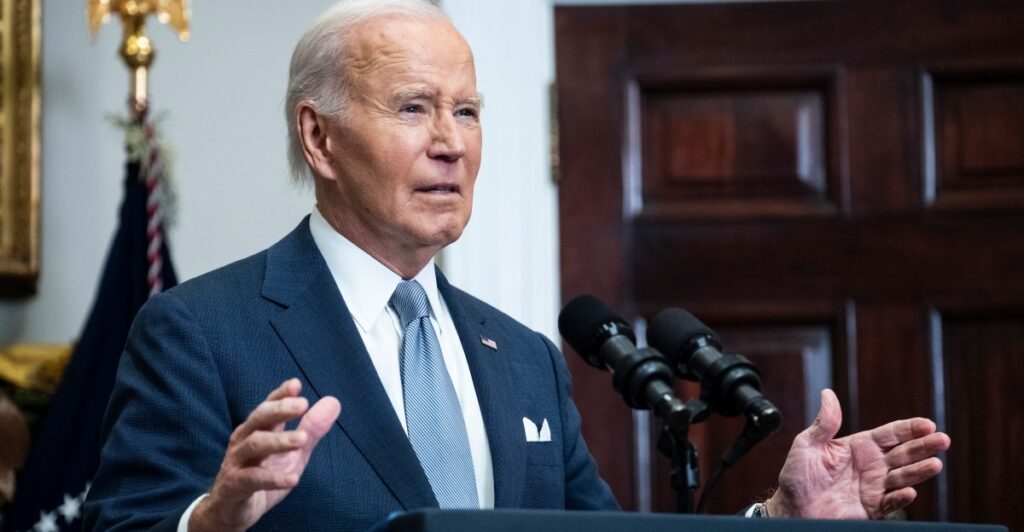

President Joe Biden commuted the sentences of nearly all federal death row inmates on Monday, meaning that 37 men who were slated to be executed will instead spend the rest of their lives behind bars without the possibility of parole. The pardons will also help contribute to what has become a notable criminal justice trend — a sharp reduction in the number of executions carried out by the United States.

Biden’s action applies only to federal prisoners — the president does not have the power to pardon or commute sentences handed down by state courts — and it leaves just three prisoners remaining on federal death row. Biden did not commute the sentences of three particularly notorious criminals: Robert Bowers, who killed 11 people at a synagogue in Pittsburgh; Dylann Roof, a white supremacist who murdered Black parishioners at a South Carolina church; and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, one of two brothers responsible for the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing.

Biden’s action will likely prevent the incoming Trump administration from beginning with a wave of executions. In 2020, the last full year of President-elect Donald Trump’s first presidency, the federal government resumed executions for the first time in two decades, killing a total of 13 people before Trump left office the first time. Biden instructed the Justice Department to issue a moratorium on additional federal executions during the first year of his presidency.

Biden’s commutations, moreover, contribute to a longstanding trend on all US death rows, both state and federal: Thanks to a variety of factors, including an overall decline in crime and better criminal defense lawyers for capital defendants, death sentences are on the decline in the United States, and have declined sharply since the 1990s. These trends are most pronounced in state criminal justice systems, which perform the overwhelming majority of executions — again, at the federal level, there have been no recent executions at all except during the later part of the first Trump administration.

For much of the 1990s, the United States (at the state and federal levels) sentenced more than 300 people a year to die. By contrast, according to the nonprofit Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC), 26 people received a death sentence in 2024, as of December 16.

According to DPIC’s data, 2024 is also the 10th consecutive year when fewer than 50 people were sentenced to die. DPIC’s data also shows a declining trend in the number of people who were actually executed (the particularly pronounced dip in 2020–2022 is likely due to the Covid-19 pandemic).

Death Penalty Information Center

That said, there are two factors that could conceivably reverse this trend. One is that the Supreme Court, with its relatively new 6-3 Republican supermajority, is extraordinarily pro-death penalty and has signaled that it may roll back longstanding precedents interpreting what limits the Constitution’s prohibition on “cruel and unusual punishments” places on government executions.

The other is that Florida recently overtook Texas as the state with the most new death sentences — a development that likely stems from a 2023 state law that allows Florida courts to impose the death penalty if eight of 12 jurors hearing a case agree to impose this sentence. Should other states adopt similar laws, that could potentially cause a rapid increase in the number of sentences. Most states require a unanimous jury verdict before a death sentence may be imposed.

Still, many of the structural factors causing the death penalty to decline are longstanding, and are unlikely to be reversed unless federal and state law changes drastically.

Why has use of the death penalty declined so sharply in the United States?

There are many factors that likely contribute to the death penalty’s decline. Among other things, crime fell sharply in recent decades — the number of murders and non-negligent manslaughters fell from nearly 25,000 in 1991 to less than 15,000 in 2010. Public support for the death penalty has also fallen sharply, from 80 percent in the mid-’90s to 53 percent in 2024, according to Gallup. And, beginning in the 1980s, many states enacted laws permitting the most serious offenders to be sentenced to life without parole instead of death — thus giving juries a way to remove such offenders from society without killing them.

Yet, as Duke University law professor Brandon Garrett argues in End of Its Rope: How Killing the Death Penalty Can Revive Criminal Justice, these and similar factors can only partially explain why the death penalty is in decline. Murders, for example, “have declined modestly since 2000 (by about 10 percent),” Garrett writes. Yet “annual death sentences have fallen by 90 percent since their peak in the 1990s.”

Garrett argues, persuasively, that one of the biggest factors driving the decline in death sentences is the fact that capital defendants typically receive far better legal representation today than they did a generation ago. As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said in 2001, “People who are well represented at trial do not get the death penalty.”

The Supreme Court briefly abolished the death penalty in Furman v. Georgia (1972). Though Furman produced a maze of concurring and dissenting opinions and no one opinion explaining the Court’s rationale, many of the justices pointed to the arbitrary manner in which death sentences were doled out. The particular death sentences before the Court in Furman, Justice Potter Stewart wrote, “are cruel and unusual in the same way that being struck by lightning is cruel and unusual” because death sentences appeared to be handed down to just a “random handful” of serious offenders.

Four years later, in Gregg v. Georgia (1976), the Court allowed states to resume sentencing serious offenders to death but only with adequate procedural safeguards. Gregg upheld a Georgia statute that allowed prosecutors to claim that a death sentence is warranted because certain “aggravating circumstances” are present, such as if the offender had a history of serious violent crime. Defense attorneys, in turn, could present the jury with “mitigating circumstances” that justified a lesser penalty, such as evidence that the defendant had a mental illness or was abused as a child. A death sentence was only warranted if the aggravating factors outweigh the mitigating factors.

This weighing test is now a centerpiece of capital trials in the United States, which means the primary job of a capital defense lawyer is often to humanize their client in the eyes of a jury. Defense counsel must explain how factors like an abusive upbringing, mental deficiencies, or personal tragedy led their client to commit a terrible crime.

Doing this well, Garrett argues, “takes a team.” It requires investigators who can dig into a client’s background, and it often requires social workers or other professionals who “have the time and the ability to elicit sensitive, embarrassing, and often humiliating evidence (e.g., family sexual abuse) that the defendant may have never disclosed.”

And yet, especially in the years following Gregg, many states didn’t provide even minimally competent legal counsel to capital defendants — much less a team that included a trained investigator and a social worker.

Virginia, for example, was once one of the three states with the most executions (alongside Texas and Oklahoma). A major reason is that, for quite some time, Virginia only paid capital defense lawyers about $13 an hour, and a lawyer’s total fee was capped at $650 per case.

In 2002, however, the state created four Regional Capital Defender offices. And, when state-employed defense teams couldn’t represent a particular client, the state started paying private lawyers up to $200 an hour for in-court work and up to $150 an hour for out-of-court work. As a result, the number of death row inmates in Virginia fell from 50 in the 1990s to just five in 2017. (Virginia abolished the death penalty entirely in 2021.)

Virginia’s experience, moreover, was hardly isolated. As Garrett notes, many states enacted laws in the last four decades that provided at least some defense resources to capital defendants.

Brandon Garrett

And in states that did not provide adequate resources to defendants, several nonprofits emerged to pick up the slack. In Texas, for example, an organization called the Gulf Region Advocacy Center (GRACE) was formed in response to a notorious case where a capital defense lawyer slept through much of his client’s trial.

Capital defendants, in other words, are much less likely to be left alone — or practically alone with an incompetent lawyer — during a trial that will decide if they live or die. And that means that they are far more likely to convince a jury that mitigating factors justify a sentence other than death.

The Supreme Court could potentially blow up this trend

The largest threat to the trend of fewer death sentences and executions is the Supreme Court’s Republican supermajority, which is often contemptuous of precedents handed down by earlier justices who Republican legal elites view as too liberal. And the Court’s most recent death penalty decisions suggest that a majority of the justices may be eager to roll back constitutional safeguards for capital defendants.

Most notably, the Court’s 5-4 decision in Bucklew v. Precythe (2019) suggests that at least some of the justices want to revolutionize the Court’s approach to criminal sentencing altogether, opening the door to far harsher sentences for many offenders.

Decisions like Furman and Gregg are rooted in the Eighth Amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishments.” This reference to “unusual” punishments suggests that the kinds of punishment forbidden by the Constitution will change over time, as certain punishments fall out of favor and thus become more unusual. As Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote in Trop v. Dulles (1958), the Eighth Amendment “must draw its meaning from the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.”

Indeed, under this framework, there is a strong argument that the death penalty has itself become unconstitutional because it is so rarely used.

Bucklew did not explicitly overrule the long line of Supreme Court precedents looking to “evolving standards of decency” to determine which punishments are allowed, but it seemed to ignore the last several decades of Eighth Amendment law altogether. Instead, Justice Neil Gorsuch’s majority opinion in Bucklew suggested that the Court’s Eighth Amendment decisions should put greater weight on what legal elites in the 1790s might have classified as cruel and unusual, than on which punishments are out of favor today.

“Death was ‘the standard penalty for all serious crimes’ at the time of the founding,” Gorsuch wrote in Bucklew. And, while his opinion does list some methods of execution — “dragging the prisoner to the place of execution, disemboweling, quartering, public dissection, and burning alive” — that violate the Eighth Amendment, Gorsuch argues that these methods of execution were unconstitutional even when the Eight Amendment was written because “by the time of the founding, these methods had long fallen out of use and so had become ‘unusual.’”

Warren’s framework, in other words, asks whether a particular punishment has fallen out of favor today. Gorsuch’s framework, by contrast, asks whether a particular punishment was out of favor at the time of the founding.

Although four other justices joined Gorsuch’s Bucklew opinion, it is as yet unclear whether a majority of the Court actually supports tossing out decades worth of Eighth Amendment law in favor of Gorsuch’s more narrow approach — since Bucklew, the Court has moved more cautiously, often ruling against death row inmates, but on narrower grounds than the sweeping reasoning Gorsuch floated in Bucklew.

Still, Bucklew does suggest that there is some appetite on the Court for an Eighth Amendment revolution. Among other things, Gorsuch’s declaration that death was “‘the standard penalty for all serious crimes’ at the time of the founding” suggests that he would overrule Gregg, with its elaborate procedural safeguards limiting when the death penalty may be used even against murderers. And the Court has only grown more conservative since Ginsburg died in 2020 and was replaced by Republican Justice Amy Coney Barrett (though Barrett has, at times, taken a less pro-death penalty approach than her other Republican colleagues.)

If Trump gets to replace more justices on the Court, and especially if he gets to replace some of the Court’s relatively moderate voices, Gorsuch could gain allies for the broader rollback of Eighth Amendment rights that he seemed to announce in Bucklew.

For the time being, however, the Supreme Court’s rightward turn has not reversed the broader trend against the death penalty. Both the number of new death sentences, and the number of executions, declined sharply since the 1990s.