Code search is a critical tool for modern software development. It enables developers to quickly locate, understand, and reuse existing code, boosting productivity and ensuring code consistency across projects.

At its core, ast-grep is a code search tool. Its other features, such as linting and code rewriting, are built upon the foundation of its code search capabilities.

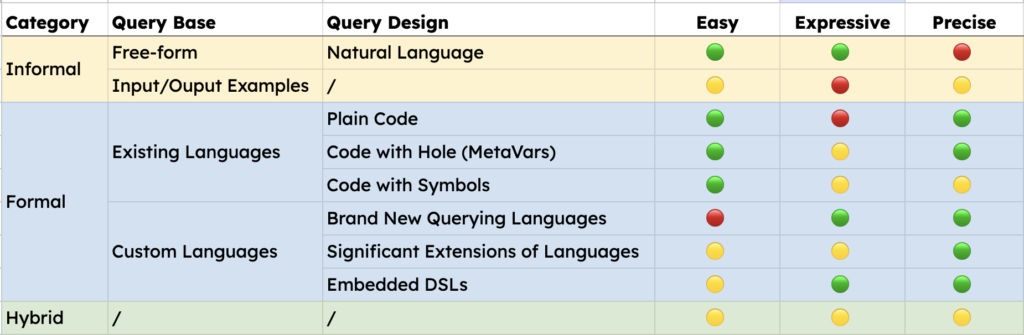

This blog post delves into the design space of code search, with a particular focus on how queries are designed and used. We’ll be drawing inspiration from the excellent paper, “Code Search: A Survey of Techniques for Finding Code”. But we won’t be covering every single detail from that paper. Instead, our focus will be on the diverse ways that code search tools allow users to express their search intent.

Query Design and Query Types

Every code search begins with a query, which is simply a way to tell the search engine what kind of code we’re looking for. The way these queries are designed is crucial. Code search tool designers aim to achieve several key goals:

Easy

A query should be easy to write, allowing users to quickly search without needing extensive learning. If it’s too difficult to write a query, people might get discouraged from using the tool altogether.

Expressive

Users should be able to express whatever they’re looking for. If the query language is too limited, you simply cannot find some results.

Precise

The query should be specific enough to yield relevant results, avoiding irrelevant findings. An imprecise query will lead to a lot of noise.

Achieving all three of these goals simultaneously is challenging, as they often pull in opposing directions. For example, a very simple and easy query language might be expressive enough, or a very precise query language might be too complex for the average user.

How do code search tools balance these goals? The blog categorizes code search queries into a few main types, each with its own characteristics: informal queries, formal queries, and hybrid queries.

Informal Queries

These queries are closest to how we naturally express ourselves, and can be further divided into:

Free-Form Queries

These are often free-form, using natural language to describe the desired code functionality, like web search. For example, “read file line by line” or “FileReader close.”

- Pros: Easy for users to formulate, similar to using a web search engine, and highly expressive.

- Cons: Can be ambiguous and less precise due to the nature of natural language and potential vocabulary mismatches between the query and the code base.

Tools like GitHub Copilot use this approach.

Input-Output Examples

These queries specify the desired behavior of the code by providing input-output pairs. You specify the desired behavior using pairs of inputs and their corresponding outputs. For example, the input “susie@mail.com” should result in the output “susie”.

- Pros: Allows to precisely specify desired behavior

- Cons: May require some effort to provide sufficient examples

This approach is more common in academic research than practical tools. This blog has not been aware of open source tools that use this approach.

We will not discuss informal queries in detail, as it is not precise.

Formal Queries Based on Existing Programming Languages

Formal queries use a structured approach, making them more precise. They can be further divided into several subcategories.

Plain Code

The simplest version involves providing an exact code snippet that needs to be matched in the codebase. For instance, a user might search for instances of the following Java snippet:

try {

File file = File.createTempFile("foo", "bar");

} catch (IOException e) {

}Not many tools directly support plain code search. They usually break search queries into smaller parts through the tokenization process, like traditional search engines.

A notable example may be grep.app.

Code with Holes

This approach involves providing code snippets with placeholders to search for code fragments. For example, a user might search for the following pattern in Java:

public void actionClose (JButton a, JFrame f) {

$$$BODY

}Here, $$$BODY is a placeholder, and the code search engine will try to locate all matching code. ast-grep falls into this category, treating the query as an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) with holes. The holes in ast-grep are called metavariables.

Other tools like gritql and the structural search feature in IntelliJ IDEA also use this technique.

Code with Pattern Matching Symbols

These queries make use of special symbols to represent and match code structures. For example, the following query in Comby attempts to find all if statements where the condition is a comparison.

if (:[var] <= :[rest])In Comby, the :[var] and :[rest] are special markers that match strings of code.

if (width <= 1280 && height <= 800) {

return 1;

}The :[var] matches any string until a <= character is found and in this case is width. :[rest] matches everything that follows, 1280 && height <= 800. Unlike ast-grep, Comby is not AST-aware, as the :[rest] in the example spans across multiple AST nodes. Tools like Comby and Shisho use this approach.

Pros and Cons

Pros: Easy to formulate for developers familiar with programming languages.

Cons: Parsing incomplete code snippets can be a challenge.

The downside of using existing languages is also emphasized in the IntelliJ IDEA documentation:

Any (SSR) template entered should be a well formed Java construction …

An off-the-shelf grammar of the programming language may not be able to parse a query because the query is incomplete or ambiguous. For example, "key": "value" is not a valid JSON object, a JSON parser will reject and will fail to create a query. Maybe it is clear to a human that it is a key-value pair, but the parser does not know that. Other examples will be like distinguishing function calls and macro invocation in C/C++.

TIP

ast-grep takes a unique approach to this problem. It uses a pattern object to represent and disambiguate a complete and valid code snippet, and then leverages a selector to extract the part that matches the query.

Formal Queries using Custom Languages

Significant Extensions of Existing Programming Languages

These languages extend existing programming languages with features like wildcard tokens or regular expression operators. For example, the pattern $(if $$ else $) $+ might be used to find all nested if-else statements in a codebase. Coccinelle and Semgrep are tools that take this approach.

Semgrep’s pattern-syntax, for example, has extensive features such as ellipsis metavariables, typed metavariables, and deep expression operators, that cannot be parsed by a standard programming language’ implementation.

Pros: These languages can be more expressive than plain programming languages.

Cons: Users need to learn new syntax and semantics and tool developers to support the extension

Difference from ast-grep

Note ast-grep also supports multi meta variables in the form of $$$VARS. Compared to Semgrep, ast-grep’s metavariables still produce valid code snippets.

We can represent also search query using Domain Specific Language

Logic-based Querying Languages

These languages utilize first-order logic or languages like Datalog to express code properties. For example, a user can find all classes with the name “HelloWorld”. Some of these languages also resemble SQL. CodeQL and Glean are two notable examples. Here is an example from CodeQL:

from If ifstmt, Stmt pass

where pass = ifstmt.getStmt(0) and

pass instanceof Pass

select ifstmt, "This 'if' statement is redundant."This CodeQL query will identify redundant if statements in Python, where the first statement within the if block is a pass statement.

Explaination of the query

from If ifstmt, Stmt pass: This part of the query defines two variables,ifstmtandpass, which will be used in the query.where pass = ifstmt.getStmt(0) and pass instanceof Pass: This part of the query filters the results. It checks if the first statement in theifstmtis aPassstatement.select ifstmt, "This 'if' statement is redundant.": This part of the query selects the results. It returns theifstmtand a message.

Pros: These languages can precisely express complex code properties beyond syntax.

Cons: Learning curve is steep.

Embedded Domain Specific Language

Embedded DSLs are using the host language to express the query. The query is embedded in the host language, and the host language provides the necessary constructs to express the query. The query is then parsed and interpreted by the tool.

There are further two flavors of embedded DSLs: configuration-based and program-based.

Configuration-based eDSL

Configuration-based eDSLs allow user to provide configuration objects that describes the query. The tool then interprets this configuration object to perform the search. ast-grep CLI and semgrep CLI both adopt this approach using YAML files.

Configuration files are more expressive than patterns and still relatively easy to write. Users usually already know the host language (YAML) and can leverage its constructs to express the query.

Program-based eDSL

Program-based eDSLs provide direct access to the AST through AST node objects.

Examples of programmatic APIs include JSCodeshift, the Code Property Graph from Joern, and ast-grep’s NAPI.

Pros: Offer more precision and expressiveness and are relatively easy to write.

Cons: The overhead to communicate between the host language and the search tool can be high.

General Purpose Like Programming Language

Finally, tools can also design their own general purpose programming languages. These languages provide a full programming language to describe code properties. GritQL is an example of this approach.

For example, this GritQL query rewrites all console.log calls to winston.debug and all console.error calls to winston.warn:

`console.$method($msg)` => `winston.$method($msg)` where {

$method <: or {

`log` => `debug`,

`error` => `warn`

}

}Explaination of the Query

-

Pattern Matching: The pattern

console.$method($msg)is used to match code where there is aconsoleobject with a method ($method) and an argument ($msg). Here,$methodand$msgare placeholders for any method and argument, respectively. -

Rewrite: The rewrite symbole

=>specifies that the matchedconsolecode should be transformed to usewinston, followed by the method ($method) and the argument ($msg). -

Method Mapping: The

whereclause specifies additional constraints on the rewrite. Specifically,$method <: or { 'log' => 'debug', 'error' => 'warn' }means:

- If

$methodislog, it should be transformed todebug. - If

$methodiserror, it should be transformed towarn.

In sum, this rule replaces console logging methods with their corresponding Winston logging methods:

console.log('message')becomeswinston.debug('message')console.error('message')becomeswinston.warn('message')

Pros: It offers more precision and expressiveness compared to simple patterns and configuration-based embedded DSLs. But it may not be as flexible as program-based eDSL nor as powerful as logic-based languages.

Cons: Have the drawback of requiring users to learn the custom language first. It is easier to learn than logic-based languages, but still requires some learning compared to using embedded DSL.

Hybrid Queries

Hybrid queries combine multiple query types. For example, you can combine free-form queries with input-output examples, or combine natural language queries with program element references.

ast-grep is a great example of a tool that uses hybrid queries. You can define patterns directly in a YAML rule or use a programmatic API.

First, you can embed the pattern in the YAML rule, like this:

rule:

pattern: console.log($A)

inside:

kind: function_declarationYou can also use the similar concept in the programmatic API

import { Lang, parse } from '@ast-grep/napi'

const sg = parse(Lang.JavaScript, code)

sg.root().find({

rule: {

pattern: 'console.log($A)',

inside: {

kind: 'function_declaration'

}

}

})This flexible design allows you to combine basic queries into larger, more complex ones, and you can always use a general-purpose language for very complex and specific searches.

ast-grep favors existing programming languages

We don’t want the user to learn a new language, but rather use the existing language constructs to describe the query. We also think TypeScript is a great language with great type system. There is no need to reinvent a new language to express code search logic.

ast-grep’s Design Choices

Designing a code search tool involves a delicate balancing act. It’s challenging to simultaneously achieve ease of use, expressiveness, and precision, as these goals often conflict. Code search tools must carefully navigate these trade-offs to meet the diverse needs of their users.

ast-grep makes specific choices to address this challenge:

- Prioritizing Familiarity: It uses pattern matching based on existing programming language syntax, making it easy for developers to start using the tool with familiar coding structures.

- Extending with Flexibility: It incorporates configuration-based (YAML) and program-based (NAPI) embedded DSLs, providing additional expressiveness for complex searches.

- Hybrid, and Progressive, Design: Its pattern matching, YAML rules, and NAPI are designed for hybrid use, allowing users to start simple and gradually add complexity. The concepts in each API are also transferable, enabling users to progressively learn more advanced techniques.

- AST-Based Precision: It emphasizes precision by requiring all queries to be AST-based, ensuring accurate results. Though it comes with the trade-off that queries should be carefully crafted.

- Multi-language Support: Instead of creating a new query language for all programming languages or significantly extending existing ones for code search purposes, which would be an enormous undertaking, ast-grep reuses the familiar syntax of the existing programming languages in its patterns. This makes the tool more approachable for developers working across multiple languages.

Additional Considerations

While we’ve focused on query design, there are other factors that influence the effectiveness of code search tools. These include:

- Offline Indexing: This is crucial for rapid offline searching. Currently, ast-grep always builds an AST in memory for each query, meaning it doesn’t support offline indexing. Tools like grep.app, which do use indexing, is faster for searching across millions of repositories.

- Information Indexing: Code search can index various kinds of information besides just code elements. Variable scopes, type information, definitions, and control and data flow are all valuable data for code search. Currently, ast-grep only indexes the AST itself.

- Retrieval Techniques: How a tool finds matching code given a query is a critical aspect. Various algorithmic and machine learning approaches exist for this. ast-grep uses a manual implementation that compares the query’s AST with the code’s AST.

- Ranking and Pruning: How search results are ordered is also a critical factor in providing good search results.