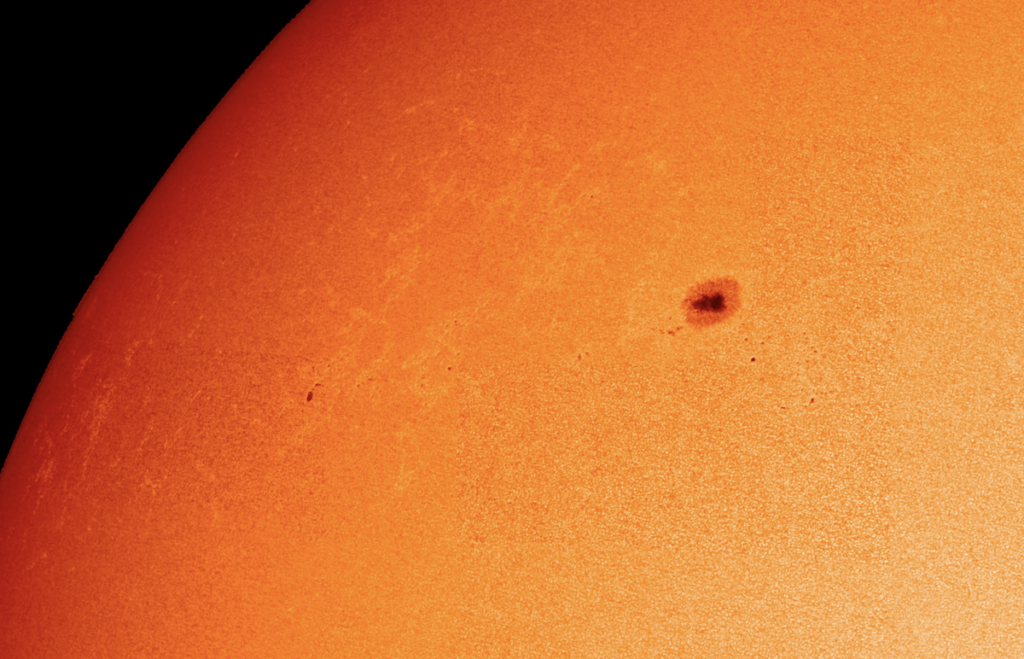

This view is just part of a new, high-resolution image of the sun’s full surface captured by the Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) on the Solar Orbiter spacecraft.

Screenshot. ESA & NASA / Solar Orbiter / PHI & EUI teams; Data processing: J. Hirzberger (MPS) & E. Kraaikamp (ROB)

The European Space Agency (ESA) has just released four new, stellar images of the sun, including the highest resolution views to date of its full, visible surface, called the photosphere.

Each image is actually a mosaic of 25 high-resolution shots snapped by the Solar Orbiter mission on March 22, 2023. The spacecraft captured all 100 total images when it was less than 46 million miles from the sun. The process took more than four hours, since the spacecraft had to change position for each individual photograph. In the final mosaics, the sun’s diameter is almost 8,000 pixels across.

“The closer we look, the more we see,” Mark Miesch, an astrophysicist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Space Weather Prediction Center who wasn’t involved with obtaining the images, tells CNN’s Ashley Strickland. “To understand the elaborate interplay between large and small; between twisted magnetic fields and churning flows, we need to behold the sun in all its splendor. These high-resolution images from Solar Orbiter bring us closer to that aspiration than ever before.”

@ESASolarOrbiter’s daring trajectory close to the Sun is paying off, giving us the highest-resolution full views of the Sun’s surface to date.

Full story https://t.co/Cy0H6JZmlp pic.twitter.com/0IyEDeLpX0— ESA Science (@esascience) November 20, 2024

The Solar Orbiter is a joint mission between the ESA and NASA, operated by the ESA, that launched in February 2020 and released its first images the following July. Since its launch, the program has hit many milestones, capturing both the closest-ever images of the sun and the first close-up images of its polar regions.

While the spacecraft totes six imaging instruments, the newly released images were captured with just two: the Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) and the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI). The PHI is responsible for three of the new solar views—an image in visible light, a map of the direction of the magnetic field and a velocity map featuring the speed and direction of parts of the sun’s surface. The EUI, meanwhile, produced an image of our star’s outer atmosphere, called the corona, in ultraviolet light.

“These new high-resolution maps from Solar Orbiter’s PHI instrument show the beauty of the sun’s surface magnetic field and flows in great detail. At the same time, they are crucial for inferring the magnetic field in the sun’s hot corona, which our EUI instrument is imaging,” Daniel Müller, a Solar Orbiter project scientist with the ESA, says in a statement. “The sun’s magnetic field is key to understanding the dynamic nature of our home star from the smallest to the largest scales.”

The four images offer a high-definition tour of the sun. First, the visible light image below depicts the star’s constantly moving surface of hot plasma—or charged gas, simply put. This layer has a temperature between 8,132 and 10,832 degrees Fahrenheit and emits most of the sun’s radiation.

The sun in visible light

ESA & NASA / Solar Orbiter / PHI Team CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

Beneath the surface is the sun’s convection zone, in which dense plasma swirls around, rather like the magma in Earth’s mantle. This phenomenon makes the sun’s surface look grainy, and scientists say the star’s magnetic field is driven by the churning plasma.

Dark shapes called sunspots are seen in both PHI’s visible light image and its magnetic map, shown below. The sun’s magnetic field is stronger at the sunspots, with red in the image indicating where it moves outward and blue indicating where it moves inward.

Sunspots are concentrated tangles of magnetic fields, where plasma is diverted from the sun’s heat-mixing convective flow, making it cooler than surrounding areas. As a result, the plasma in sunspots gives off less light and appears dark in the visible light image.

This map, showing the line-of-sight direction of the sun’s magnetic field, is also called a magnetogram.

ESA & NASA / Solar Orbiter / PHI Team CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

In the third image—the velocity map, shown below—the PHI captures the movement of parts of the sun’s surface, with blue indicating movement toward the Solar Orbiter and red indicating movement away from it.

“This map shows that while the plasma on the surface of the sun generally rotates with the sun’s overall spin around its axis, it is pushed outward around the sunspots,” according to the statement.

The velocity map, also called a tachogram

ESA & NASA / Solar Orbiter / PHI Team CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

Lastly, the EUI’s ultraviolet light image captures the sun’s corona—its wispy outer atmosphere that can only be seen from Earth during a total solar eclipse. The image depicts interesting activity once again around the sunspots: plasma shooting outward along magnetic field lines, which occasionally connect sunspots close to each other.

This high-resolution image shows the sun in ultraviolet light, revealing its outer atmosphere, the corona.

ESA & NASA / Solar Orbiter / EUI Team CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

The image processing that produced the PHI’s images was “new and difficult,” per the statement, but moving forward, ESA experts expect to produce similar images with greater speed, potentially releasing two a year.

“This mission is such a treasure and important to science,” Günther Hasinger, director of science for the ESA, told Space.com’s Amy Thompson at the time of its launch.