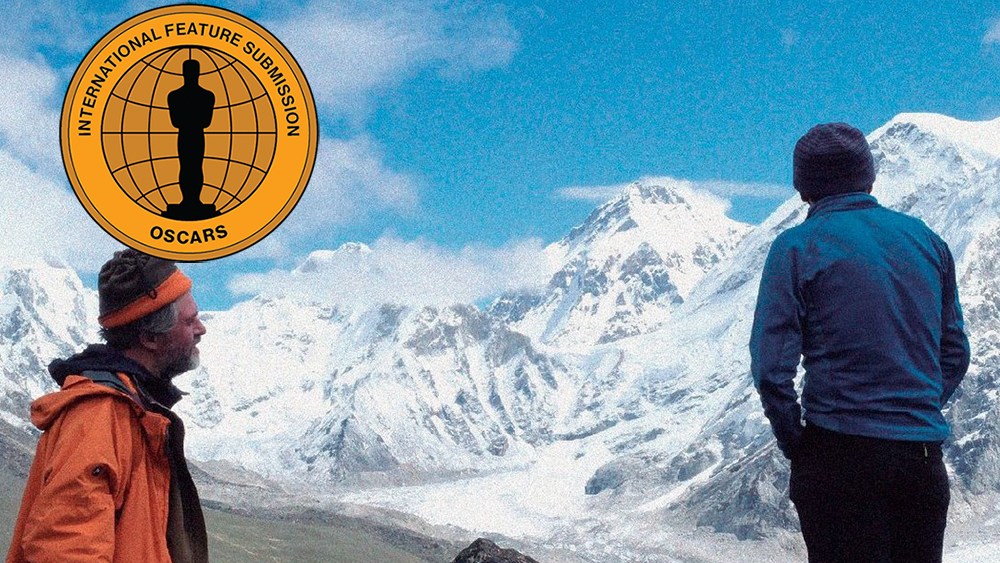

There’s a haunting quality to Ecuadorian Oscar submission “Behind the Mist,” Sebastián Cordero’s intimate documentary on scaling Mount Everest. On one hand, Cordero’s twinning of mountaineering and filmmaking reveals spiritual similarities to both endeavors. On the other hand, his visual texture reveals hidden layers through its lo-fi aesthetic — one that emerges by necessity, given the harsh conditions — resulting in images that feel introspective about their own creation.

Cordero’s main subject is Iván Vallejo, the first Ecuadorian to reach Everest’s peak — without the help of Pxygen too. After achieving this feat in 1999 (and again in 2001), Vallejo hopes to commemorate his climb by returning to the top of the world in 2019. Naturally, he invites Cordero along to document him, but the filmmaker and the mountain maverick have opposing ideas of what the movie (and perhaps, movies in general) should be.

This search ends up taking philosophical form, as the “Europa Report” director trades in a moon of Jupiter for the peaks of Nepal, as seen through a DIY digital camera following discussions about everything from Camus to family issues with Vallejo. At its simplest, the movie captures scenes of the famous mountaineer against the pristine, icy Himalayas as he reminisces, and explains his point of view on art and adventure — a line that slowly begins to blur.

However, this more retro documentarian form is often broken up by a roving lens that seems to fall, most often, on religious tradition and iconography, as though Cordero were looking to the region’s Hindu and Buddhist traditions for cinematic enlightenment. At one point, he even follows the camera around an enormous, spinning, cylindrical prayer wheel housed in a hut, as though he were praying for answers. With each revolution, the camera enters a darkened space, filled with visual noise, before emerging back into the light near the dwelling’s door, as if to achieve a form of temporary enlightenment before losing it again. This process, which happens multiple times throughout the film, also embodies the cycles of birth and rebirth in the aforementioned faiths — not unlike Stephanie Spray and Pacho Velez’s documentary “Manakamana,” in which the camera moves through light and dark spaces along a cable car to a Nepalese temple — as though Cordero were nearing liberation through enlightenment, or nirvana, but not quite achieving it.

The movie’s rough quality feels intimate and spontaneous, though the duo’s sense of time is discombobulated, as mirrored by alternating shots of sped-up and slowed-down footage. All the while, temple bells ring in the background, weaving together even the most disparate-seeming images into something rhythmic. Images and dialogue are often edited parabolically; they overlap to emphasize the herculean nature of scaling an enormous mountain and creating from imagination, as though they were born from the same impulse — the same curiosity.

Cordero furthers this notion by mirroring his memories with Vallejo’s. Just as the famous climber looks back to his record-setting 1999 summit though old photographs, Cordero thinks back to his 1999 debut feature “Ratas, ratones, rateros” and links the two men in time by incorporating photographs from the former alongside footage from the latter in essayistic fashion. His matter-of-fact voiceover, while authoritative, laments that movie’s lack of success. He seems to disguise a quest for answers about what he does (and why), just as Vallejo second-guesses his dedication to his own chosen obsession, by ruminating on what it’s cost him.

But the further the duo climbs, the more the movie seems to find itself. At first, neither man can see the full picture. The peaks Vallejo hopes to glimpse are hidden in the clouds, and the inspiration Cordero hopes will strike seems shrouded in fog. Mountaineering, like moviemaking, is a leap of faith, and in “Behind the Mist, these things are driven by same impulse to get in touch with one’s past and spirit.

It can be hard to diagnose how Cordero himself feels, whether during the time the film was made — his presence is mostly behind the camera, and therefore spectral — or, for that matter, in retrospect. But there’s a distinct moment of technical and spiritual harmony in the third act when the movie’s soul is laid bare, perhaps inadvertently. It’s a beautiful moment of Vallejo reaching a snowcapped peak, so bright and reflective that the entire image is washed out, but for Vallejo himself and a few nearby rocks. The snow is falling, swiftly and forcefully, and the reduced motion blur of Cordero’s camera in these moments causes not just a jittery effect, but results in the snowfall illuminating Vallejo and the rock in particular, enveloping them in a living haze unseen elsewhere in the frame, as though this unassuming person and object were ethereally bound, across time and space.

Perhaps it’s a happy accident, but the film is so meticulous in its quest that a moment like this was bound to appear, in which everything just feels right, and both Vallejo, and “Behind The Mist,” suddenly make perfect sense. Few documentaries about death-defying feats have felt as peaceful and calming.