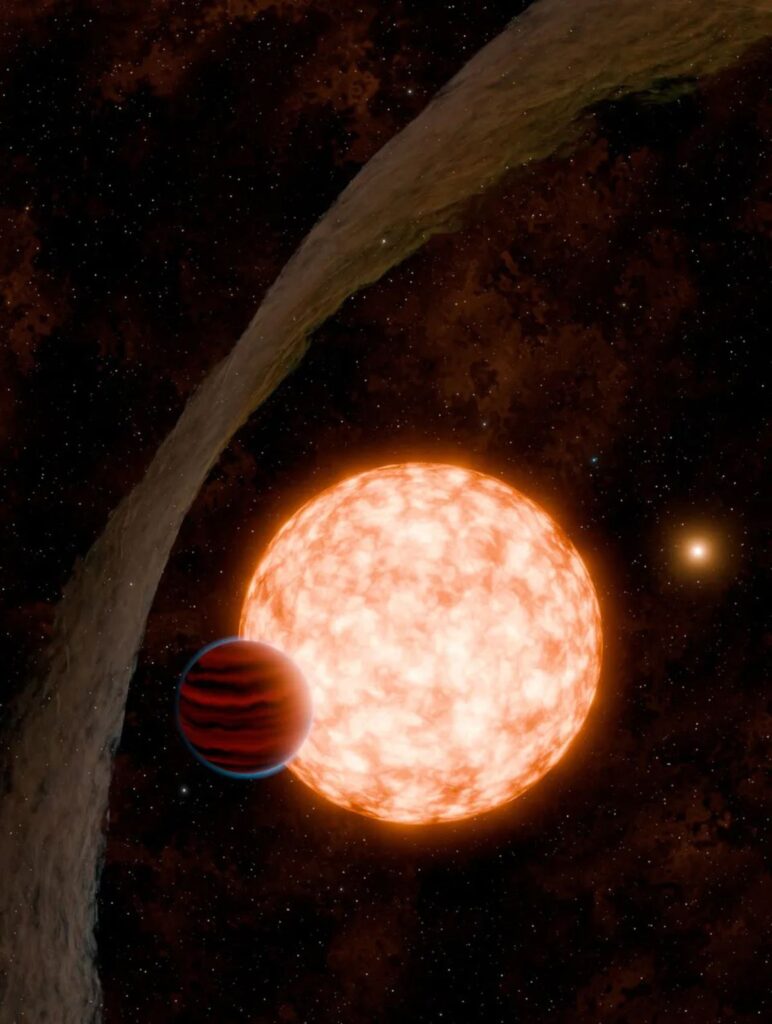

An artist’s interpretation of the newly discovered planet and a warped debris disk

NASA / JPL-Caltech

A recent discovery of a “newborn” exoplanet could help scientists explain how our own home world came to be.

In a study published Wednesday in the journal Nature, astronomers describe the youngest transiting planet ever found. It’s about three million years old—a baby, in cosmic terms. If you imagine Earth as a 50-year-old adult, this world would be a two-week-old infant, in comparison.

The discovery was made by Madyson Barber, a graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and lead author of the study. The new find marks Barber’s third planet discovery.

While it’s not her first, “this is definitely our biggest one, because it’s the youngest transiting system,” she tells ABC News’ Julia Jacobo. “There’s so much we can learn by looking outwards to learn more about our own home and where we come from and where we might be going.”

The planet—named both IRAS 04125+2902 b and TIDYE-1b—orbits what will likely become an orange dwarf star, about 520 light-years from Earth, and circles its host every 8.8 days. Reuters’ Will Dunham writes that its mass is between that of Earth and Neptune—less dense than our home planet but holding “a diameter about 11 times greater.”

Barber spotted evidence of the distant world during a transit, when a planet passes between a star and its observer. Most exoplanets are discovered through transits, where scientists measure a decrease in the brightness of a star due to a planet passing in front of it. Sure enough, Barber noticed “little dips” in starlight coming from the system, indicating the transit of a planet, per ABC News. But this seemed odd, given the young age of the star.

According to the study, while astronomers have found more than a dozen planets transiting stars that range from 10 million to 40 million years old, “younger transiting planets have remained elusive.” That’s because nascent solar systems contain a protoplanetary disk circling around the young host star—a ring of material that eventually coalesces to create other celestial bodies. Typically, this disk surrounds the star for its first five million to ten million years and blocks astronomers from viewing younger planets.

But in the star system with TIDYE-1b, the outer protoplanetary disk is uniquely misaligned, and the inner disk is depleted, providing astronomers a chance to view the planet.

“We don’t really know how long it takes for planets to form,” study co-author Andrew Mann, an astronomer at UNC Chapel Hill, tells Reuters. “We know that giant planets must form faster than their disk dissipates, because they need a lot of gas from the disk. But disks take five to ten million years to dissipate. So do planets form in one million years? Five? Ten?”

Barber tells Reuters the discovery confirms planets can reach a cohesive form within three million years. Earth took 10 million to 20 million years to form, she adds, so this new finding helps add information about early planets.

“We try to extrapolate from these other worlds how quickly planet formation might have taken hold in the early solar system,” Melinda Soares-Furtado, an astrophysicist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who was not involved with the research, tells New Scientist’s Jonathan O’Callaghan.

The researchers are currently 95 percent confident in their measurements of TIDYE-1b’s upper mass limit and believe it could be a “precursor of the super-Earth and sub-Neptune planets that are frequently found orbiting main sequence stars,” ABC News writes. Main sequence stars, like the sun, compose nearly 90 percent of the stars in the known universe and fuse hydrogen atoms to form helium in their cores.

“Because we don’t have a ton of these young transiting systems that we know of, it’s really important that we look for more so that we can have a better picture of what that formation and evolution looks like, so we can better understand how our own home formed and evolved,” Barber tells ABC News.