By Lorris Chevalier

Was Dante’s journey through Hell a reflection of his own inner battles? Recent scholarship suggests that the intense themes of violence and redemption in The Divine Comedy may reveal traces of trauma from his time as a soldier in medieval Italy.

Dante Alighieri, best known for his monumental Divine Comedy, was not only a poet and philosopher but also a soldier and politician in a turbulent period of Italian history. His life was marked by intense political conflict, social upheaval, and personal strife. Now, scholars are exploring how his works reflect not only intellectual and theological concerns but also the emotional scars of war. While “post-traumatic stress disorder” (PTSD) was a concept unknown in Dante’s time, readers can discern signs of trauma likely stemming from his military experiences. The vivid imagery, emotional volatility, and thematic preoccupations of The Divine Comedy may reveal a soul grappling with the effects of conflict.

Dante’s Military Life: A Prelude to Trauma

Dante’s involvement in Florence’s political and military strife is well-documented. He fought in the Battle of Campaldino in 1289, siding with the Guelphs against the Ghibellines in a brutal and bloody encounter. Still in his twenties, Dante faced the horrors of medieval warfare: close-quarters combat, the death of comrades, and the general chaos of battle. Such events would have left a lasting psychological impact on anyone involved.

Although he rarely spoke directly of his military service, the historical context of his life suggests that his battlefield experience was deeply formative. The emotional toll of combat, combined with his subsequent exile from Florence and personal losses, may have contributed to a form of post-traumatic stress that found expression in his literary work.

Echoes of Battle in The Divine Comedy

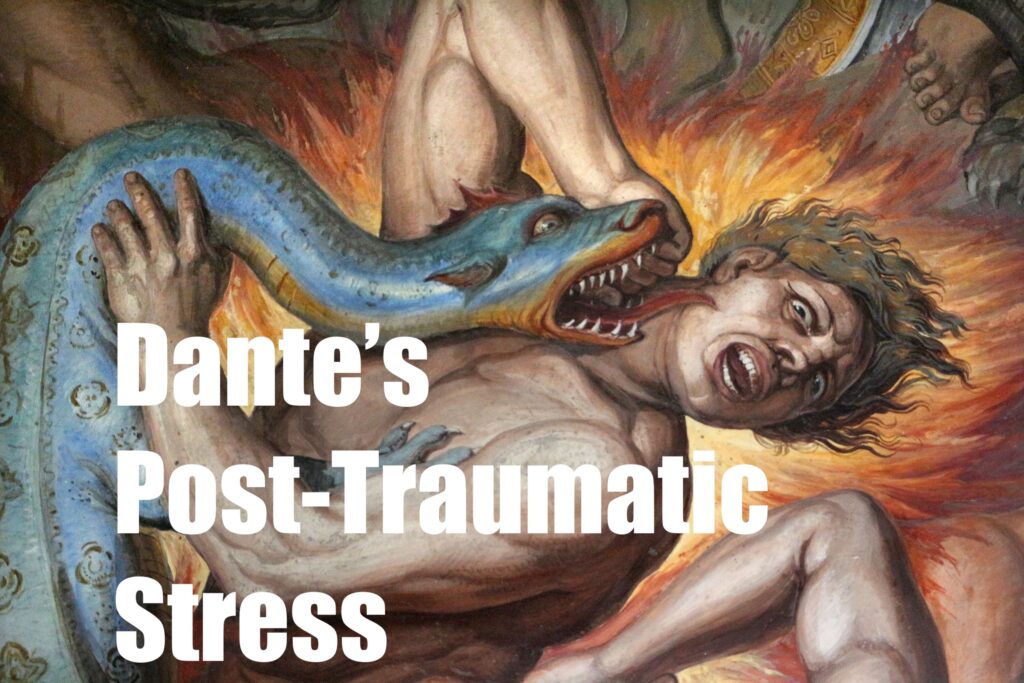

In The Divine Comedy, Dante embarks on a journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven. Scholars often see his vivid descriptions of Hell as more than just allegory. The raw, intense emotions that accompany the depictions of suffering souls and Dante’s repeated returns to the theme of violence and retribution may reflect his own haunting experiences. Here are three ways that it can be seen:

1. Vivid Depictions of Violence and Suffering

Dante’s Hell is filled with grotesque and graphic scenes of violence, governed by the contrapasso—the principle that sinners suffer in ways that match their sins. For instance, murderers are submerged in a river of boiling blood, a visceral image evoking the carnage of battle. These depictions are detailed and intense, suggesting a mind reliving the horrors of combat.

The imagery in Inferno, with dismembered bodies, tormented souls, and endless suffering, could mirror intrusive thoughts, a hallmark symptom of PTSD. Dante’s focus on the physical and emotional suffering of the damned and his fascination with scenes of violence indicate a preoccupation with trauma.

2. Survivor’s Guilt and Grief

Dante’s journey through Hell includes frequent encounters with figures from his past, including former comrades and enemies. Many of these souls are people he knew, some suffering terribly for their sins. His reactions are complex—he feels pity but also acknowledges the justice of their punishment.

This emotional ambivalence hints at a kind of survivor’s guilt, a sense of being haunted by the dead and questioning the fairness of his survival. His volatility during these encounters suggests unresolved grief and guilt, common among those who have experienced war. In his meeting with Farinata degli Uberti, a Ghibelline leader who fought against him, there is both respect and tension, underscoring Dante’s unresolved feelings about his past as a soldier and exile.

3. Nightmares and Flashbacks

Dante describes moments of intense fear and confusion throughout Inferno, including episodes where he nearly faints from terror. These scenes resemble what modern psychology might label flashbacks—sudden, overwhelming memories of traumatic events. His journey often feels like a nightmare where he is repeatedly confronted with terrifying aspects of his past.

For example, Dante’s encounter with Filippo Argenti, a personal enemy, evokes a visceral reaction. Dante bursts with anger, wishing Argenti further torment, suggesting a psychological re-experiencing of his political and personal battles.

Exile: A Compounding Trauma

Dante’s exile from Florence in 1302, after being on the losing side of political conflicts, added to his sense of loss and dislocation. Exile was a profound trauma; he was cut off from his home, family, and everything familiar, wandering for years on the charity of others. This profound displacement and isolation are themes that pervade his later works.

In Paradiso, even as Dante reaches the heights of Heaven, he yearns for peace and resolution. His journey, though ultimately redemptive, mirrors his search for healing after the upheavals of his life. His exile reflects the inner exile of a mind struggling with trauma, his works an ongoing search for solace.

Dante’s Divine Comedy is more than an allegorical journey through the afterlife; it reflects the poet’s inner world, shaped by violent and tumultuous experiences. His war service, the political turmoil in Florence, and his exile left psychological scars, manifesting through his focus on violence, guilt, and redemption. While a formal PTSD diagnosis is impossible, his work clearly reveals the toll of trauma, offering a window into the soul of a man who saw and suffered greatly.

Reading Dante through the lens of trauma deepens our understanding of his experience and the universal themes of suffering and healing that continue to resonate today. His work shows us that trauma and redemption are timeless, drawing readers to confront their own battles and emerge with a sense of purpose.

Dr Lorris Chevalier, who has a Ph.D. in medieval literature, is a historical advisor for movies, including The Last Duel and Napoleon

See also: New Medieval Books: Dante’s Divine Comedy: A Biography

Top Image: Casa Massimo frescos – stanza di Dante – Walls by Joseph Anton Koch. Photo by Saliko / Wikimedia Commons

Subscribe to Medievalverse