Recently the Dutch Electoral Board (where I am also a very part time advisor) invited me to do a talk reflecting on their open source Abacus vote tabulation software.

Much software is now provided as a service, and is typically deployed continuously (CD, continuous deployment), surrounded by enough automated testing (CI, continuous integration) that we can be reasonably sure that a new revision is likely to at least work to some extent.

In contrast, there is also still a huge world where people don’t appreciate such continuous changes combined with only a pretty good likelihood of things working. Software that controls (nuclear) power plants, elections, pacemakers, airplanes, bridges, heavy machinery. In general, stuff that can kill you if it does the wrong thing, or perhaps simply by not working.

These fields appreciate your software sticking around for decades, with well described and pre-announced changes. Release notes that go beyond “various bug fixes and improvements”. Software that might not see any changes for a few years, after which a new major release gets planned, and stuff still needs to build from source.

Crazy talk of course, but some of us like it this way!

The presentation consisted of a generic part on long term software development, and a specific critique of their software development so far.

For the generic part, I asked my friends on Mastodon to weigh in:

Mastodon delivered in spades, and most of this post is derived from input from kind Mastodonians.

Now, nothing what follows is particularly earth shattering. However, the strength of certain recommendations is noteworthy, and might give you some pause.

At an extremely high level, we can think about software like this. There is an outside world that we don’t control, for example client software (like browsers). Realities we have to deal with. Within our own software, we have certain very fundamental base choices, like which programming languages to use. Switching programming languages effectively requires a rewrite of the whole stack, so you don’t do that lightly.

Somewhat above that we often find frameworks which couple tightly with our codebase. Think of web/JavaScript frameworks, object relational mappers (ORMs), stuff like Spring Framework, Ruby on Rails, React, Rust Axum etc. While you could switch out such a dependency, it is (very) heavy lifting. It touches lots of your code.

Next up, almost everything will depend on some kind of database. There are many databases around, but most of them work more or less the same. If you built on MySQL and you come to your senses and shift to something else, you’ll have real work to do, but it is mostly in the details and specifics.

Finally, there are mostly interchangeable “helpers”. Libraries that perform some function for you here and there, but are mostly “point” solutions. You could rip and replace such a dependency likely without even having to tell your users.

Now, from the above it is clear that if you are thinking long term, dependencies are extremely important. You depend on them. However, since we can’t devote maximum attention to everything, we should think far harder about the bottom of the pyramid than the top. And such thinking is necessary since on multi-year timescales, your dependencies and the outside world do not sit still:

One overwhelming bit of feedback after my Mastodon post was to severely limit your dependencies, because all of them might over time:

- Drift away, leading to adjustments in your code or, worse, silent changes in behaviour

- Shift to new major versions with semantic changes, requiring rewrites on your part

- Get abandoned or simply disappear, or start to decay

- Get hijacked by (nation state) actors (think npm, pypi etc)

- Start to get monetized by the new VC owner

- Develop conflicting dependency requirements of their own

(I’ve personally been burned on Python by the last bullet point where one of the dependencies required version 3.14 or less of module such and such, and another dependency needed 3.15 or higher)

Now this is not a call for doing without dependencies of course! They are inevitable for getting stuff done. But when extrapolated over a 10 year time frame, we must take an extremely critical look at what code we are going to rely on:

- Does the tech look good if you look at the source code? And can you?

- Who else uses this dependency?

- Who writes it? Why?

- What are their goals?

- Are they funded? By whom?

- Is maintenance happening? Do you see security releases?

- Is there a community that could take over maintenance?

- Could I take over maintenance if need be?

- Should I fund/support them to make sure they stay around?

- And what about their dependencies?

- What is the security track record there?

If this looks like big work, you’d be right. This easily takes hours/days per dependency to figure out. Incidentally, this is why I think adding dependencies to a project should be somewhat hard work technically. That gives you some natural pause to think if it is a good idea!

What might not be a great idea is to have 1600 dependencies in 2024, dependencies which already change at such a rapid clip your code base is effectively a moving target. To be honest, you don’t know what you are shipping if your code draws from over a thousand dependencies, mostly ones you have no direct knowledge of.

Runtime dependencies

So far we’ve been talking about build/compile-time dependencies. Many projects these days however also have runtime dependencies, like perhaps S3, or Google Firebase. Some of these things are informally pretty well standardised (like S3), but other things are effectively a lock-in. In short, if you plan on a 10 year horizon, you need to have an extremely short or empty list of third party services you rely on. It is going to be extremely expensive in 2034 to find an exact workalike of what you are based on now.

This is especially relevant for ‘cloud native’ software development that uses many intricate or higher level third party services.

Of special note also are build-time service dependencies. If ’npm install’ (or equivalent) no longer works for some reason, can you even build your software?

Did I say testing? Everyone was clear on this front. Have as many tests as possible. There was some argument that not all tests are equally valuable, and this is of course true. But you’ll almost never regret a test. Tests are always a good idea, especially if you have many dependencies which shift and drift all the time. Tests will not prevent this from happening, but they will help you get started earlier to adjust to the changed situation.

Tests will also give you (mental) support while refactoring, or removing dependencies. In addition, after a 3 year hiatus in development, tests are a great way to reestablish that you still have a functioning system, even when using newer compilers, runtimes, operating systems etc. Write more tests.

Now, this is not new ground, but it bears reiterating: complexity is the end-boss of software development. Complexity can slay the best programmer and even the best team. It is the ultimate enemy. Yet, because of entropy and human behaviour, complexity will always increase unless you act upon it consciously.

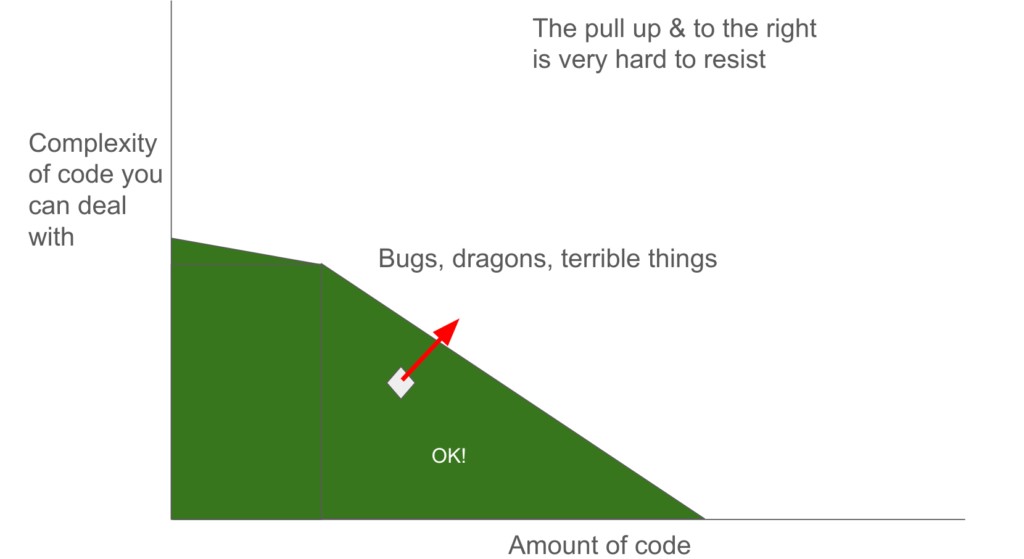

Although this is well-trodden material, I think this graph is somewhat of a novelty. But in all honesty, I’m probably channeling something I read earlier:

If you have a limited amount of code to deal with, this code could be quite complex in nature. As the amount of code increases, it needs to be ever simpler if you still want to have a handle on it. As long as your code is in the green triangle, and your team stays competent, you are good. But you can’t arbitrarily reshape the green area:

Even if you hire more people and/or people with bigger brains, there is a hard limit to how much complexity we can deal with. On a good day, even. And once your code has escaped the green area, you are hosed. And as the arrow shows, the natural movement of your code is ‘up and to the right’. People demand more features, programmers like to optimize stuff even when there is no need, and even required bug fixes often add a lot of new code (instead of doing the scarier work to undo the underlying complexity that likely led to the bug).

Over time, complexity only adds up. There is cognitive load involved in dealing with a function called CreateFile that does not actually create a file most of the time. Paring back such misnamed functions or counter-intuitive APIs is of utmost importance. Oddly behaving calls and methods offer fresh opportunities to trip you up every day.

So the message from the field was unequivocal: refactor early and often, remove unneeded code, take time to simplify. Or you will inevitably end up in an unmaintainable swamp in the course of your 10+ year software project. And note that this will be easier to do if you invested in tons of tests.

“Everyone knows that debugging is twice as hard as writing a program in the first place. So if you’re as clever as you can be when you write it, how will you ever debug it?” – Brian Kernighan

Write super boring code. Write naive but obvious code. “Premature optimization is the root of all evil”. If it was too simple, you can always make it more complex later. And that moment might never arrive. Don’t write clever code until you simply have to. You will not ever regret writing code that was simple.

Especially be aware of high performance code/functionality that only works if you “hold it just right”. I’m a great fan of LMDB for example, but PowerDNS went through quite some pain before we were able to reliably benefit from its awesome speed and capabilities. Similarly, I’ve used RapidJSON, a SIMD-accelerated JSON library, but eventually found the edges too sharp. Too much juggling of chainsaws.

The scary thing is however that such technologies might appeal to you – “I can deal with these constraints, and reap the awesome performance rewards”. This may be true on a good day this year. But you, or your replacement, might struggle 5 years from now. This also goes for complex programming languages by the way.

But seriously, keep it simple. Even simpler than that. Really.

So what technology are we going to use? In theory we should follow our dependency checklist from above to determine that. In reality, this is often an almost subconscious decision where someone tries something that looks attractive, and if it works, we run with it.

Such attractiveness can come from LinkedIn posts by esteemed thought leaders and influencers. It could also come from Hacker News users raving over the latest glorious framework to end all frameworks.

Now, it might be that such hyped technologies are worth the hype. But it is probably best to recognize that new stuff has yet to prove its longevity. Best use it in experimental places and keep it away from the 10-year software project for now. According to the Lindy effect for many things, their longevity is proportional to their current age.

One issue with software that is not updated/deployed continuously to millions of users is that you do not get that instant feedback moments after you broke the website. Although oddly enough, even there it can take quite some time before the message reaches the people that can fix it.

Feedback from Mastodon was to make sure that your software somehow logs its performance, failure and activities very well. Starting from your earliest releases. Over the years, having such data will prove invaluable in solving uncommon bugs from deployments that may run your software once every few months.

I once accidentally deployed a UI to customers meant to list only a few things. What the user never told me was that they created 3000 folders, but they did tell me that nothing worked anymore. Better (performance) logging/telemetry would’ve saved me months of pain there.

We all know we should document more, no news there. But the feedback I got was quite clear that there are specific things we need to document. You can these days quite easily churn out very attractive looking API documentation. This does not tell you however WHY things are like this. What is the idea behind how the system works? Is there a philosophy? Is there a specific reason why we do these non-obvious things? Why is the solution split up the way it is?

This stuff goes beyond writing architecture documents, although you should definitely also write those. But you could also think about (internal) blog posts by developers, or interviews with teams. Shoot the breeze on why it all came out like that.

7 years from now with a mostly new team, the knowledge in such documents is priceless. “Yeah the system is single threaded, and let me tell you why”.

Specifically, I got feedback that despite the craze that good code needs no comments, code definitely needs comments. Especially why a function is like that. Other feedback was to work on commit messages, which is something I’d like to support, but then also make sure that people can easily see those commit messages.

Personally, I have days where my brain isn’t well setup for writing more code, but I could definitely spend that day writing useful comments and notes. It might be a great idea to schedule time for that for teams as well.

Some of the feedback came from people with software that supports an 80-year mission (!). It is quite common for teams to turn over quite quickly these days. In many places, 3 years is quite the tenure. Although you can counteract such turnover with good documentation and great tests, it is hard work. One of the easiest hacks for successful software longevity is keeping people around for a decade. This means actually hiring them as employees and taking good care of your programmers. Crazy right?

In some places, software development is performed by consultants, who leave after dropping their code in your systems. This is roundly seen as a very bad idea under most circumstances if you are aiming for decade-long sustained software quality.

Now, this is not always or even often something you can do. But having your code exposed to outside eyes is a great way of keeping yourself honest. One fun anecdote is that companies or governments will often say they need months or years to prepare (CLEAN UP) code for open sourcing. Because on the inside, people allow themselves far worse code than they’d prefer to share with the outside world. Open source code often has higher standards, and it is a great mechanism of keeping you on track.

If you can get away with it of course.

I wrote above how dependencies can evolve to drift or shift away from where we expect them to be. If you do nothing, you discover this because of bugs, build failures or other disappointments. One recommendation from Mastodon was to periodically schedule a wellness check on your dependencies. This could also bring positive surprises. It is well possible that one of your dependencies has grown new capabilities for example, which might make it possible to simplify your code. Or scrap another dependency.

If you spend time on this maintenance, you discover issues at a moment of your choosing. Or as mechanics say, schedule time for maintenance, or your equipment will schedule it for you.

As noted this is all well trodden ground, and here are some books that have done the trodding:

- The Practice of Programming, Brian W. Kernighan, Rob Pike. Full of stuff that should be obvious, but in practice is not yet obvious enough. Even though this is mostly about C, the lessons are universal.

- The mythical man-month, Fred Brooks. Called “The Bible of Software Engineering”, because “everybody quotes it, some people read it, and a few people go by it”.

- A philosophy of software design, John Ousterhout – a modern take by a seasoned professional.

- Large Scale C++ Software Design, John Lakos – I would not specifically recommend buying this book since much of what it describes is quite specific to old-style C++. However, if you chance on this work, its stories on very large scale software development are illustrative of the art. Has valuable words on how circular dependencies crop up, and how much they suck.

Overwhelmingly, these are the recommendations for long-term software development:

- Keep it simple. Simpler than that. Yes, even simpler. You can always add the complexity later if needed!

- Keeping it simple requires periodic refactoring / code deletion

- Think real real hard about your dependencies. Fewer is likely better. Scrutinize and audit. And if you find you can’t audit 1600 dependencies, rethink your plan. Don’t go for LinkedIn-based development choices.

- Re-visit your dependencies periodically to see how they are doing

- Testing, testing, testing! Will help you spot shifting dependencies in time, will give you confidence to do the refactoring you need to keep things simple

- Document all the things, not just the code, but also the philosophy, the idea, the “why”

- Aim for a steady team. Get actual employees with a long-time investment in your project

- If you can get away with it, ponder being open source

- Logging, (performance) telemetry will save your bacon over the years

None of these things are novel, but the vehemence with which veteran developers exhort us to think hard about these recommendations should give us pause.

Finally, I want to thank the large cast of Mastodon users who weighed in with their decade long experiences. Your help was most appreciated! In addition, the material was improved significantly by the great questions & reflections from my colleagues at the Dutch Electoral Board.

If you have any further feedback, or disagreement, do let me know on bert@hubertnet.nl!