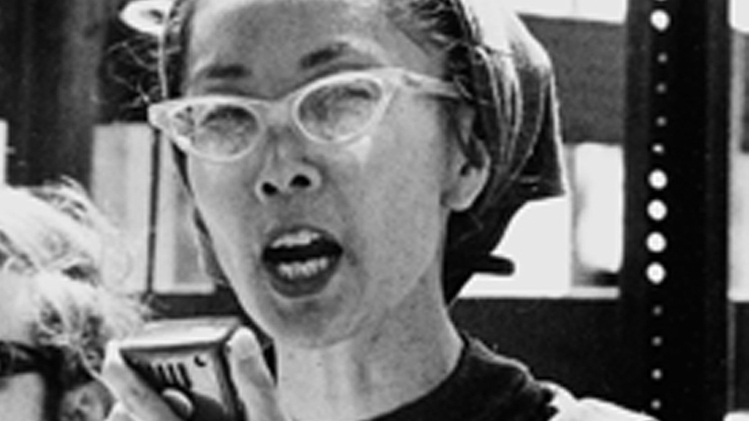

Yuri Kochiyama speaks at an anti-war demonstration in New York City’s Central Park around 1968.

Courtesy of the Kochiyama family/UCLA Asian American Studies Center

hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of the Kochiyama family/UCLA Asian American Studies Center

Yuri Kochiyama speaks at an anti-war demonstration in New York City’s Central Park around 1968.

Courtesy of the Kochiyama family/UCLA Asian American Studies Center

On March 5, 1965, LIFE Magazine published an article on the assassination of Malcolm X. The article was accompanied by a photo of Malcolm X lying on the floor—his white button-down shirt ripped open and stained red with blood—moments after the fatal shots were fired. In the photo is a woman kneeling on the ground, her hands holding up Malcolm’s head, appearing to give him comfort in his dying moments. There is no mention of who the bespectacled woman is or her relation to Malcolm X in the article, but that woman remembered that tragic moment vividly. Her name is Yuri Kochiyama.

A Japanese American activist whose early political awakenings came while incarcerated in the concentration camps of World War II America, Kochiyama dedicated her life to social justice and liberation movements. As hate crimes against Asian American Pacific Islanders surge, Throughline reflects on Yuri Kochiyama’s ideas around the Asian American struggle, and what solidarity and intersectionality can mean for all struggles.

Co-hosts Rund Abdelfatah and Ramtin Arablouei spoke to Diane Fujino, professor of Asian American studies at UC Santa Barbara and author of the book, Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama. Fujino had the opportunity to interview Yuri Kochiyama multiple times for her biography. Below are highlights from a conversation with Fujino on the latest episode of Throughline. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

On the detaining of Japanese Americans during WWII:

DIANE FUJINO: It helped her to recognize herself as a Japanese American. This is what Yuri says. And to see the strength of the Japanese American community and to survive as not just individuals, but to come together as a community. You know people grew gardens, right? They figured out how to put up partitions in the bathrooms, to have a little privacy and dignity. There was so much that that happened. There were protests inside the concentration camps. She listened to discussions of more politicized Japanese Americans inside the camps. And I would say she started to grow a social consciousness, a sense that problems in the United States had social and structural origins.

RUND ABDELFATAH: I noticed that you called what are typically referred to as Japanese internment camps, concentration camps. And I wonder if that was intentional and why you decided to use that term?

FUJINO: Evacuation refers to moving to safety but that’s not what happened. It was forced, right? It was done through racial profiling and racism against a group who were the descendants of supposedly the enemy and, yet, we know that mass incarceration didn’t happen for Germans and Italian Americans. And so what the Japanese American activist community has called upon for decades is that they be called concentration camps. And when people say, well, doesn’t that diminish what happened in Nazi Germany? The response has been that those were death camps, but these, that Yuri and Japanese Americans were placed in, were concentration camps. There was barbed wire, there were sentries, they were forced to move to be placed into them. Their freedoms were limited.

On how Kochiyama became involved in activism while living in Harlem:

FUJINO: She became an activist and an organizer in her 40s as the mother of six children. She got involved in supporting better quality schools for the children of Harlem, now including her own children. And then she got involved in a labor struggle at a medical site where they were going to build a new medical building and were doing their typical discrimination in hiring. She was following the news of the Civil Rights Movement unfolding on television and in the newspapers. And she was seeing things like water cannons blasting peaceful Black protesters, dogs being sicced on peaceful Black protesters.

On what solidarity meant to Kochiyama:

RAMTIN ARABLOUEI: In a moment like we’re living through right now where it feels like every few months it feels like a new group of people, whether Black Americans or Asian Americans, or for a time it was Muslim or Middle Eastern Americans, or of course Native Americans are targeted, what does her example tell us about the need to see that connectivity between the groups that are being targeted?

FUJINO: Yes, I think that there are two crucial lessons: The first one is this need for solidarity that we cannot only look to the interests of our own people. First of all, who are our own people? Many of us cross multiple groups and at the same time, working only out of self-interest gets us in a trap. It’s like the model minority myth where we work out of self-interest but the gains that one group makes come at the expense of other groups. This is not a model of liberation. It’s a very problematic model and one that Yuri always resisted. [She] always said and operated by the ethos that my people’s liberation is intricately linked to your people’s liberation. I cannot be free if you’re not free. We need to think about how things impact the most vulnerable among us and work out of those best interests.

The second thing that I think is really crucial here is that we cannot just work in reactionary ways every time there’s an incident–a new incident of an attack on Asian Americans, yet another police killing of an unarmed Black person, or attacks against indigenous peoples and their lands and waters–this gets us nowhere. It’s a constant battle and it’s exhausting. And what’s most important is that we build movements for liberation.

If you would like to learn more about Yuri Kochiyama: