Early this year I was alerted to the opportunity to acquire this unusual lithograph from 1865. I was surprised to find that neither the Library of Congress nor the New York Public Library, which has a large collection of digitized images, had this image in their holdings.

After conservation, I offered it for sale in a hand made, solid wood frame through our Rare Finds, and I asked art historian Deb Stein to provide additional information on this unique print. Her excellent piece is below. — Lee Wright | Founder

By Deb Stein

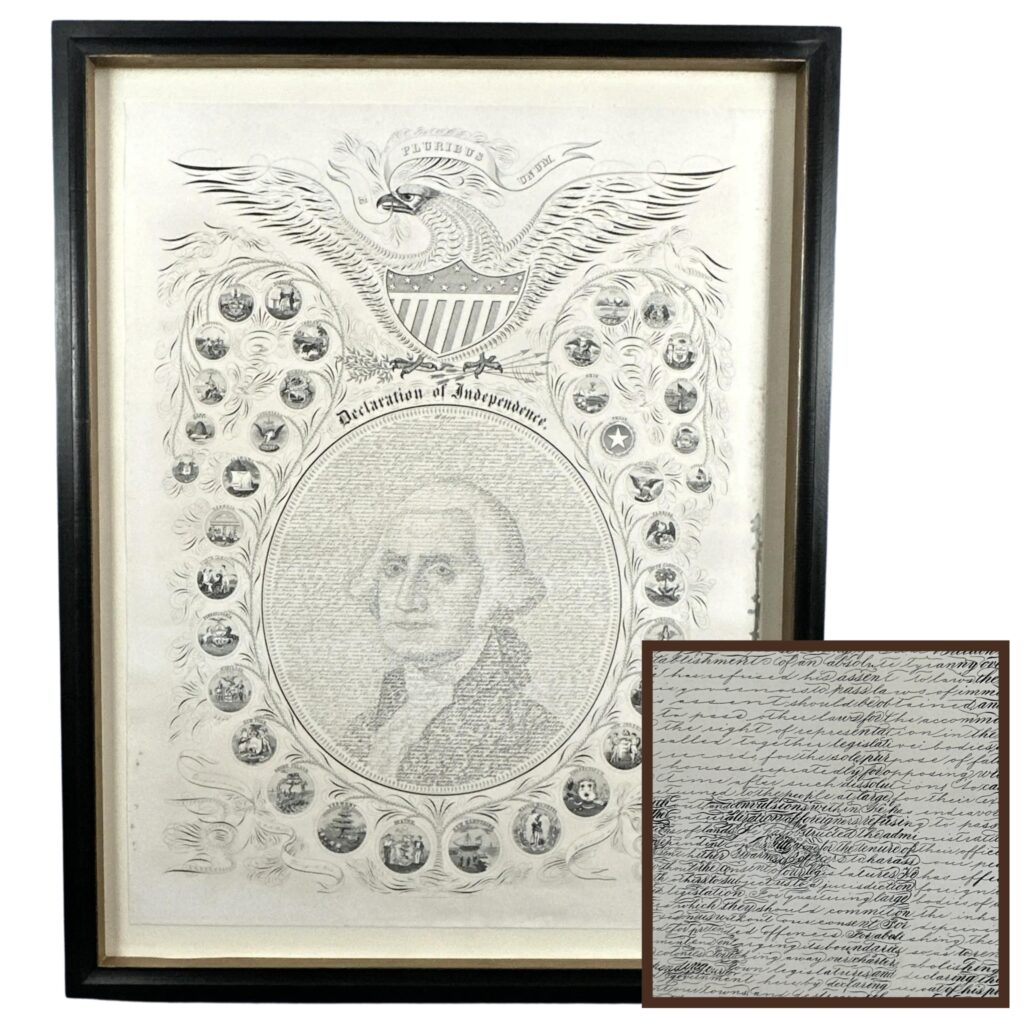

The choice of subject matter alone, George Washington and the Declaration of Independence, tells us that this calligraphic print celebrates the founding of the United States of America. But if we studied it more closely, would it have more to tell us about its time and place?

The following discussion of the print’s date of production, its method of production, its historical context, its design details, and its makers would suggest that there is much that deepens and enlivens our understanding of the American past.

The print is undated. One thing is clear, however. The date is not coincident with the signing of the Declaration of Independence or with George Washington’s presidency.

As denoted in the title of the print, there are 36 state seals surrounding George Washington’s three-quarter profile, each one of them further identified by the state name. There were, of course, only thirteen “states” at the time the Declaration was published. According to the dates of admission of states to the Union, the 36th state was admitted in 1864 and the 37th in 1867, thus fixing the print’s date to the period of 1864 to 1867.

Further to the date, the method of printing is that of lithography, invented at the end of the eighteenth century in Germany, and not introduced in the United States until c. 1820, thus postdating by several decades the time of the Declaration and Washington’s presidency.

The impact of lithography

Lithography propelled the printing business into high gear. Rather than the centuries-old processes that applied ink to images that were either raised or hollowed out (termed “relief”and “intaglio” respectively), both labor-intense processes, lithography allowed imagery (including text) to be simply drawn on stone with a greasy crayon. Because the crayon marks did not easily degrade, a far greater number of impressions could be created than was the case with relief and intaglio methods.

In addition, the method allowed for larger prints and a greater scope in design. In the early 1820s, these advantages, already capitalized upon by entrepreneurs and printers in Europe, took hold in the United States, with lithographic businesses springing up, first in New York, and then in Washington, D.C., Boston, and Philadelphia. ¹

The final clue to the date comes from the printmakers themselves, as we do know who they are. They have identified themselves elegantly in the decorative flourishes at the bottom of the print.

The designer and calligrapher, William Henry Pratt, was an instructor in penmanship. He was born in Boston in 1822 and moved to Davenport, Iowa in 1857, where he became Director of the Davenport Commercial College, and ultimately helped to found the Davenport Academy of Natural Sciences. Augustus Hageboeck was both the lithographer and the printer. He was active from the early 1860s to 1886, running a lithographic business in Davenport with his brother. ²

Taking the dates attributed to Pratt and Hageboeck together with the inclusion of the 36 state seals and the use of lithography, we can confidently conclude that the print dates to 1864 to 1867.

With a better fix on the date of the print, we can consider its historical and cultural context.

The interest in new imagery

Throughout the Civil War and its aftermath, the American public — mostly in the North, as the economic damage in the South precluded much in the way of artistic production — was hungry for all matter of printed imagery about the conflict, gobbling up prints that told the stories of the momentous battles, whether won or lost, the gallant leadership, and the heroic commitment of not only those on the front, but those at home.

In fact, the prints were so important to their owners that they were often framed and hung on the wall, thus proudly putting on display their loyalty to the Union cause. ³

Calligraphic prints, that is prints that utilized the art of “beautiful, stylized, or elegant handwriting or lettering with pen or brush and ink” (as defined by the Encyclopedia Britannica online) were a popular category of print in the Civil War era.

c. 1860 Spencerian penmanship sign from New England Auctions, Branford, Connecticut

The choice of calligraphy as the chief element of design was not random. Beautiful penmanship was not only prized for its pleasing appearance, but it was also considered fundamental to an enlightened mind, thus connecting it with no less an elevated value than democracy itself. ⁴

This calligraphic print of George Washington and the Declaration of Independence really showcases the beauty and impact of the genre.

First, the lettering is eminently graceful with its flourishes and rhythmic flow at the same time as it impresses with its perfectly uniform imprint of a massive amount of text onto a relatively small surface.

Second, it is actually the bolding of the letters themselves that creates the outlines of Washington’s head, facial features and clothing. ⁵ Highlighted by their central position within the bolded oval frame, Washington’s profile and the words of the Declaration thus form the dominant feature of the print.

Prints of Washington and Lincoln

In the aftermath of his heroic preservation of the Union, and then his assassination, Abraham Lincoln was understandably much the favorite subject for printmakers. ⁶ Indeed, several years before it produced the Washington print, the same design team used the identical calligraphic format to feature Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation.

That said, imagery of the first president was by no means uncommon throughout the Civil War period. In fact, it was Lincoln himself who was largely responsible for this as he regularly evoked Washington’s honor, courage, and foresight, thus linking himself to the legendary figure.

In the early years of the Civil War, Washington was featured in group portraits of the sixteen presidents, imagery intended to emphasize “the continuity of both the Union and the institution of the presidency in the face of secession and rebellion.” ⁷

Even when Lincoln’s emphasis moved from preserving the union to freeing the slaves, “evoking comparisons between the two presidents remained, for graphic artists, irresistible, and for their audiences, inescapable.” ⁸ And after Lincoln was assassinated, images depicting his apotheosis often featured Washington as the God-like figure welcoming his worthy successor into heaven.

The later date of the calligraphic portrait of Washington notwithstanding, it is no less a paean to the founder and the Declaration. This is because the text of the founding document is literally what shapes the founder’s image.

The net effect is that Washington and this founding document are virtually one and the same, presenting an unshakeable defense of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” ⁹

Ultimately, this print speaks volumes regarding its time and place. That it gives us a more nuanced understanding of momentous connections across time in American history, as represented by our first and sixteenth presidents and by the Declaration of Independence and the Emancipation Proclamation, is particularly gratifying.

That connection is perhaps nowhere better expressed than in Abraham Lincoln’s own appraisal of the Declaration as “a rebuke and a stumbling block to tyranny and oppression.” ¹⁰

Deb Stein, PhD, is an independent art historian specializing in eighteenth and nineteenth-century American and European art history and a Visiting Lecturer at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts.

¹ This discussion of the invention and early adoption of lithography is owed to the following sources: Colta Ives, “Lithography in the Nineteenth Century,” in: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000): http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/lith/hd_lith.htm (October 2004); Erika Piola, Philadelphia on Stone: The First Fifty Years of Commercial Lithography, 1828-1878: http:///www.librarycompany.org/pos/.

² Biographical details gleaned from https://emuseum.mountvernon.org/objects/16796/declaration-of-independence; https://www.si.edu/object/proclamation-emancipation%3Anmah_324929

³ Discussion of the market for prints during the Civil War is owed to the following sources: Elizabeth O’Leary, review of Eleanor Jones Harvey, The Civil War and American Art in: The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 121, no. 3 (2013): 294-295; Review of Mark E. Neely and Harold Holzer, Popular Prints of the Civil

War North in: Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 36, no. 1 (Spring 2001): 70-71.

⁴ The online discussion of the MFA Boston’s “Emancipation Proclamation, with calligraphic portrait of Abraham Lincoln,” suggests that “beautiful handwriting was not just an elegant attainment, it was a marketable skill.” (Accession number 2013.825); www.mfa.org. The connections between penmanship and the mind are explored in Richard S. Christen, “John Jenkins and ‘The Art of Writing’: Handwriting and Identity in the Early American Republic”, The New England Quarterly, vol. 85, no. 3 (September 2012): 491-525.

⁵ Harold Holzer, “’Columbia’s Noblest Sons’: Washington and Lincoln in Popular Prints,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, vol. 15, no. 1 (Winter 1994): 61.

⁶ The discussion of Civil War imagery of both Lincoln and Washington is indebted to Holzer, “Columbia’s Noblest Sons,” 23-69.

⁷ Holzer, “Columbia’s Noblest Sons,” 29.

⁸ Ibid., 33-34.

⁹ Online discussion of the MFA Boston’s “Emancipation Proclamation”, (Accession number 2013.825), www.mfa.org describes how the union of text and portrait mean that “Lincoln literally embodies his greatest achievement: the freeing of the slaves.”

¹⁰ As quoted in the National Archives essay on the Declaration of Independence https://www.archives.gov/