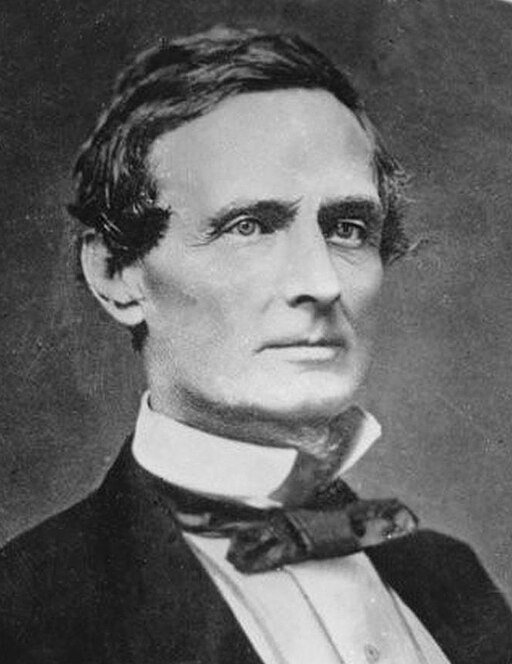

Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States, in 1862.

“When the dogmas of a sectional party…threatened to destroy the sovereign rights of the States, six of those States, withdrawing from the Union, confederated together to exercise the right and perform the duty of instituting a Government which would better secure the liberties for the preservation of which that Union was established.”

– Jefferson Davis Inaugural Address, Richmond, Virginia, 1862

“It was clear from the actions of the Montgomery convention that the goal of the new converts to secessionist was not to establish a slaveholder’s reactionary utopia. What they really wanted was to create the Union as it had been before the rise of the new Republican party.”

– Robert Divine, T.H Bren, George Fredrickson, and R Williams, America Past and Present, HarperCollins, 1995

The original states that left the Union did so as separate and sovereign republics but soon entered into a confederacy.[1] Their capital was located in Montgomery, Alabama. Delegates from the seceding states joined together and formed the Confederate Constitution on March 11, 1861. The South sought to restore the Constitution as the founders originally intended it to be.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis said, “The constitution framed by our founders is that of these confederate states.” When the state legislators of Texas joined the Confederacy, they informed the crowd gathered in Austin on April 1, 1861, that “The people will see that the Constitution of the Confederate States of America is copied almost entirely from the Constitution of the United States. The few changes made are admitted by all to be improvements. Let every man compare the new with the old and see for himself that we still cling to the old Constitution made by our fathers.” As historian Marshall DeRosa summarized in Redeeming American Democracy, “The confederate revolution of 1861 was a reactionary revolution aimed at the restoration of an American democracy as embodied in the Constitution of 1789.”

While the Confederate constitution was in many ways nearly identical to that of the old Union, the North had taught the South how a majority could eradicate constitutional liberty. Consequently, the Southern statesmen sought to prevent tyranny in their Confederacy. The Confederate Constitution differs from the United States constitution in various areas as the South sought to preserve self-government via diverse self-governing states. To accomplish this end, they strictly limited central powers. As a result, the differences between the documents can tell us about the causes that led to the Southern withdrawal.

Confederate State Sovereignty

We, the people of the Confederate States, each State acting in its sovereign and independent character, in order to form a permanent federal government, establish justice, insure domestic tranquillity, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity — invoking the favor and guidance of Almighty God — do ordain and establish this Constitution for the Confederate States of America.

– Confederate Constitution Preamble

The creators of the southern Constitution made it clear that the states were sovereign. In the Confederacy, no one would be able to claim that authority rested with the central government as Republicans had in the old Union. The United States Constitution reads, “We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect Union….” the Confederate version reads, “We the people of the Confederate States, each state acting in its sovereign and independent character …”

As sovereign confederated states, they could exercise nullification or secession to protect their citizens from federal coercion. We will discuss nullification and secession in more detail in a later chapter, but they were the two antebellum modes of dealing with the federal government when it stepped past its delegated powers. In The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, Confederate president Jefferson Davis wrote, “It was not necessary in the Constitution to affirm the right of secession, because it…was an attribute of sovereignty, and the states had reserved all which they had not delegated.” The southern states that ratified the Confederate Constitution kept the right to secession in their state constitutions. For example, the Alabama state constitution reads:

Section 2. All political power is inherent in the people, and all free governments are founded on their authority and instituted for their benefit; and that, therefore, they have at all times an inalienable and indefeasible right to change their form of government in such manner as they may deem expedient.

According to a well-known secession document we call The Declaration of Independence, it is an inalienable right to have a government that represents you and not a distant majority or a powerful national party. Southerners believed this was no less true in 1861.

In response to claims made by Lincoln, the Confederate Constitution also declared that the people of the states had sovereignty and not the entirety of people. Each state was separate from the others and sovereign within its jurisdiction. Decentralization, or “states’ rights,” allowed multiple diverse sets of governments to coexist; it preserved self-governance and benefited “we the people.” Decentralization, or localism, is based on populations creating laws organically for their benefit. To get a sense of what decentralization provides, imagine your preferred political party (not just your party, but your brand of the party) winning every election at every level. Not only that, you would not have to spend time and money fighting the other party to prevent men from gaining power that you don’t want them to have. You could create unified blocs of society and live with like-minded people.

On the other hand, centralization occurs when forces far from these self-governing localities impose their ways on numerous smaller localities because of their power and influence. In such a situation, the former free individuals, over time, lose their self-governance and ability to choose from a diverse set of customs. Instead, they become tools to benefit those in power in distant lands under the increasingly conformist policy. The only people decentralization harms are the powerful bureaucrats and politicians. They seek to plunder our wealth to redistribute it to friends and interest groups and purchase a voting bloc to maintain power.

The Southern move towards decentralization is well known and widely accepted. For example, in Redeeming American Democracy, Confederate Constitution scholar Marshall DeRosa wrote, “The confederate framers placed the government firmly under the heads of the states.” In The Confederate States of America, Southern historian E Merton Colter stated, “States rights dogma…produced secession and the confederacy.” In his book Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E Lee, Michael Korda said the South’s “first concern was states’ rights.” In Ken Burn’s Civil War documentary, the narrator states, “The Confederacy was founded upon decentralization.” Southern writer Lochlainn Seabrook, in his book The Constitution of the Confederate States of America, explained that the Confederacy put “emphasis on small government and states’ rights.” Professor Marshall DeRosa quotes Judge Robertson of Confederate Virginia Supreme Court Case Burroughs v Peyton in 1864 as stating, “{The Confederate} Congress can have no such power over state officers. The state governments are an essential part of the political system, upon the separate and independent sovereignty of the states, the foundation of the Confederacy rests.”

The South removed the term “general welfare” from the preamble since Republicans used the term to claim the federal government had powers for their federally funded internal improvements. In the Confederate Constitution, the states had the right to recall powers delegated, not granted to Congress. The CSA’s 10th amendment gave the state authority over the federal government. Due to the fact the states were sovereign, the Confederacy never even organized a supreme court.[2] When discussion in the South arose over a supreme court, William Yancy of Alabama said, “When we decide that the state courts are of inferior dignity to this court, we have sapped the main pillars of this confederacy.” In The State Courts and the Confederate Constitution Journal of Southern History, J G DeRoulhac Hamilton wrote, “The fear of centralizing tendencies, past experiences under the federal supreme court, and a desire to protect states’ rights led to the failure to establish a confederate supreme court.”

Further, the states, not Congress, had the power to amend the Constitution, and a state convention could occur to modify the Constitution without federal involvement. Just three states were needed to call a convention, so a minority section, as the South had been under the old Union, could prevent bullying by concentration of power within the Confederacy.

The state officials elected senators to represent their states and appointed them to protect against federal officials, they were truly representing their states. They were not just another number to be counted in national party voting wars.[3] Confederate officials working in a state were subject to impeachment by that state. Even the country’s capital would not be permanent but move from state to state to avoid centralizing power.

There were no political parties within the Confederacy. Instead of power being handed over to bureaucrats, big industry, and private interest groups, the people would maintain control. The South, in general, disliked campaigns associated with elections, and the CSA Presidents could not be reelected for this reason. In 1861, Alexander Stephens told Virginians, “One of the greatest evils in the old government was the scramble for public offices—connected with the Presidential election. This evil is entirely obviated under the Constitution, which we have adopted.”[4]

Fiscal Responsibility and Anti-Discrimination

“One leading idea runs through the whole—the preservation of that time-honored Constitutional liberty which they inherited from their fathers….the rights of the States and the sovereign equality of each is fully recognized—more fully than under the old Constitution…But all the changes—every one of them—are upon what is called the conservative side take the Constitution and read it, and you will find that every change in it from the old Constitution is conservative.”

– Hon. Alexander H. Stephens, Speech to the Virginia Secession Convention, April 23, 1861

The Confederate constitution was more libertarian economically than the U.S. version. In her article, Cash for Combat, published in the Americas Civil War magazine, Christine Kreiser wrote, “The Confederacy was founded on the proposition that the central government should stay out of its citizen’s pockets.”

The federal government was extremely limited in its spending. The Constitution required fair trade, a uniform tax code, and omnibus bills to be restricted. Because subsidies and corporate bailouts were excluded, lobbyists and bureaucrats would struggle to advance their agendas. To avoid special favors for supporters and to disrupt the lifeblood of corruption and political parties, Congress would handle each bill separately to guarantee that politicians could not sneak in favors for their supporters. This would help encourage actual statesmen to represent their local communities (states) at the federal level instead of purchasing campaigning politicians working for political parties and capitalists.

The post office had to be self-sufficient within two years of ratification. The CSA President had a line-item veto on spending, and no cost overruns were allowed on any contracts. These changes would help to hold elected officials accountable and keep them honest. Politicians would be forced to give an actual cost to a proposed bill, and if it were to exceed the price, they would be held accountable. A failed project due to cost overruns would not only devastate those who pushed for it, but would turn the voters against any future proposed endeavors. And a greater consensus was needed to pass expenditure bills in the first place.

“The question of building up class interests, or fostering one branch of industry to the prejudice of another, under the exercise of the revenue power, which gave us so much trouble under the old Constitution, is put at rest forever under the new. We allow the imposition of no duty with a view of giving an advantage to one class of persons, in any trade or business, over those of another. All, under our system, stand upon the same broad principles of perfect equality.”

– Alexander Stephens “Cornerstone Address,” March 21, 1861

Likewise, politicians could not steal from one section of the country and give to another; they could not set one section of people against another to plunder the despised section, and Congress could not foster any one branch of any industry over another. Speaking to the Virginia

Convention, Vice President Stephens said, “No money shall be appropriated from the common treasury for internal improvement, leaving all such matters for the local and state authorities. The tariff question is also settled.” These changes would help stifle any internal hatred and anger caused by setting one section or party of the country against another.

Jeb Smith is the author of Missing Monarchy: What Americans Get Wrong About Monarchy, Democracy, Feudalism, And Liberty (Amazon US | Amazon UK) and Defending Dixie’s Land: What Every American Should Know About The South And The Civil War (written under the name Isaac. C. Bishop) – Amazon US | Amazon UK

You can contact Jeb at jackson18611096@gmail.com

[1] This article was taken with permission from a section of Defending Dixie’s Land: What Every American Should Know About The South And The Civil War.

[2] Such was provided for in article III of the Confederate Constitution, but was never set up.

[3] Of course this was also true of the United States at this time, the situation changing with the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913.

[4] For more examples of the CSA Constitution moving to decentralization, see Redeeming American Democracy Lessons From the Confederate Constitution by Professor Marshall DeRosa; The Confederate Constitution of 1861 An Inquiry into American Constitutionalism by Marshall DeRosa;; The Constitution of the Confederate States of America Explained, A Clause-by-Clause Study of the South’s Magna Carta by Lochlainn Seabrook; and The Confederate States of America, 1861—1865 by E.Merton Coulter.