Four hundred years ago — on New Year’s Day in 1624 — drifting ice on the river Lek in the Netherlands smashed up a dike outside Utrecht. This was a pretty big problem in a country that is roughly one-third below sea level.

Soon, the region was flooded, with even Amsterdam threatened by the water. The locals eventually managed to staunch the flood, but they still needed to do a full, durable rebuild — which would be extremely expensive.

Fortunately, the Dutch were brilliant, sophisticated financial pioneers, and had developed the era’s most vibrant bond market. The local water authority — called Hoogheemraadschap Lekdijk Bovendams — swiftly sold over 50 bonds that raised about 23,000 Carolus guilders to finance the repairs.

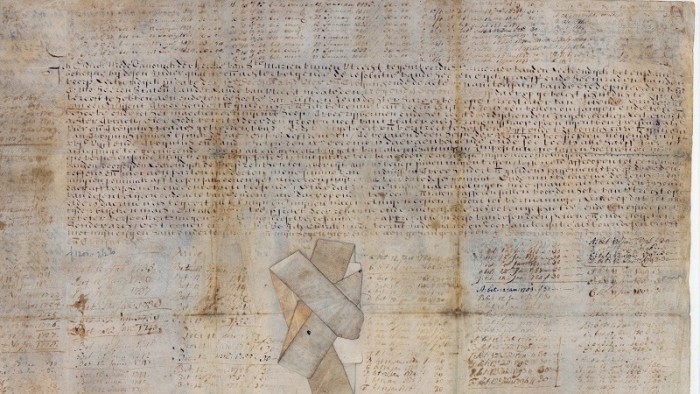

Of these bonds the only surviving one is a 1,200 guilder bond sold on December 10, 1624, to a wealthy woman in Amsterdam called Elsken Jorisdochter. In return for her money, the water board promised Jorisdochter, her descendants or anyone who owned the bearer bond 2.5 per cent interest in perpetuity.

Remarkably, this bond is still alive and pays €13.61 of interest a year. Yesterday, the current owner — the New York Stock Exchange — collected £299.42 of owed interest for the bond’s 400th birthday, which FT Alphaville was able to attend.

Keen readers will remember that FTAV wrote about the handful of surviving Dutch perpetuals last year. So why are we banging on about this again?

Well, partly because this bond is a physical, living reminder of how fixed-income markets built the modern world, which bears repeating. Bonds have won wars and broken countries. They have funded hospitals, slave-worked tobacco farms and sugar plantations. They’re now bankrolling the data centres and chips that power artificial intelligence, as well as more obvious boondoggles, like Manchester United.

As a result, it’s highly likely that over half of all global debt is in the form of bonds rather than loans (comprehensive and accurate global data on this is patchy). This is a big deal, as MainFT laid out in a magazine piece last year.

To take but one example, America’s biggest lender is no longer a bank; it’s BlackRock. Here are a few big banks and asset managers ranked by the size of their lending in the form of bonds or loans.

But mostly we keep going on about it because this is so obviously amazing. The 1624 bond is a financial wonder of the world. If you don’t like a four-century-old Dutch goatskin perpetual that still pays interest then I’m afraid we can’t be friends.

With that in mind, here are some more details about the genesis of the world’s oldest living bond, and Tuesday’s 400th birthday celebration — we even got pretty little cakes decorated with the original coat of arms of the issuer.

The first thing to understand is that water authorities like the Hoogheemraadschap Lekdijk Bovendams were hardcore.

After all, in Europe’s flood-ridden lowlands — the Netherlands was sometimes called the bog of Europe — they were a matter of life and death. Not just to you, your family and your community, but the neighbouring village or town as well.

In 1323 the count of Holland sent his army to burn down a town as punishment for it not having done necessary repairs to its dykes, according to William Goetzmann and Geert Rouwenhorst’s The Origins of Value. Until the 19th century, the water authorities enjoyed legal rights to punish local slackers, including branding, flogging, banishment and execution. The Rijnland water board even had its own gallows and a whipping post next to one of its dikes, which sends a pretty powerful signal.

And they took paying their debts just as seriously. The Hoogheemraadschap Lekdijk Bovendams no longer exists, but its modern descendant is the Hoogheemraadschap De Stichtse Rijnlanden, which is based just outside Utrecht. The original bond was signed on December 10, 1624 in a building that is now part of Utrecht University, which hosted the event in the very same building yesterday.

Most of the bonds the Lekdijk Bovendams issued were eventually bought back — they could be redeemed at any time at the discretion of the water authority — while others have been lost over the years. But De Stichtse Rijnlanden still services seven of these Methuselah bonds, of which the 1624 one is the oldest.

Pictured here is the bond, the “allonge” where individual payments are noted down now that the back of the bond itself is full, and the hard coins that De Stichtse Rijnlanden produced out of a chest for the occasion.

And here is what the text of the bond itself says, translated from old Dutch. Dense, but a lot less wordy than most bond prospectuses today.

I, Didirck Mode, Canon of the Church of St Mary within Utrecht present Treasurer of the Leckendijck Bovendams declare herewith, in that function and following the decision of the Gentlemen Dike Governor and Board of the said Leckendijck dated the 9th December 1624 and the subsequent deed of authorisation of the executive committee of their Mightinesses the Estates of the province of Utrecht dated the 9th of December aforesaid, to owe and have sold to and for the benefit of Elsken Jorisdochter, her inheritors or anyone possessing claim the sum of one thousand two hundred Carolus guilders which I declare to have received in full from the said Elsken Jorisdochter for the purpose of building a new quay, two willow shore guards and a straight new dike stretch for the damaged Lek dike beyond Tiel which (God willing) because of the very high water and strong ice drift on New Year’s Day 1624 broke.

[I also declare] to have awarded and given 75 Carolus guilders of twenty stivers apiece per year as heritable annuity, to be paid one half of the annuity aforesaid on the 9 th of June 1625 and the other half the 9th of December following and so on every six months until repayment with all payments entirely free of all taxes, impositions or burdens of whatever name or title none excepted.

On such conditions that I or my successors [unreadable] of the aforesaid Leckendijck may, at any time when it pleases us, extinguish, repay, and buy back the said annuity in full at once and not in parts or fractions with the sum of one thousand two hundred Carolus guilders aforesaid and not a penny less and the stiver valued as those minted before this date on condition of paying the interests then due and unpaid and on condition that I and my successors in the aforesaid function accept the contents of this and will register and pass a deed of obligation pertaining to it before the Court of Utrecht or elsewhere if so desired at my cost or that of my successors at once on demand.

And in order that it may be clear forever that everything written here has been effected by the decision and authorisation mentioned above, and in order that parties may be better assured, that decision and approval will be written on the back of this and signed without reserve. Towards that end have I, aforesaid Didirck Mode, in the function and by authorization as above, signed this document with my own hand and affixed my seal thereunder on the 10th December 1624.

The 1624 bond ended up in NYSE’s possession thanks to a Dutch-American banker called Albert Andriesse, a senior partner in Pierson & Co. and board member of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange.

Andriesse acquired the perpetual at an auction as a historical curio, and on a 1938 visit to New York donated it to the NYSE as a sign of friendship, given how 1624 was the year the city was founded as New Amsterdam.

Two years later, Andriesse and his family fled the Netherlands to escape the Nazis, and settled in New York in 1941. There he became an American citizen before passing away in 1965.

Even at the time his gift was novel enough to get a brief notice in the New York Times, with the following clip courtesy of his granddaughter, who was at yesterday’s interest payment ceremony.

Just take a moment to think about what this bond has survived.

The borders of the country now called the Netherlands have changed enormously over the years. There have been multiple revolutions, several pandemics, four different currencies and countless wars. Napoleon subsumed the country entirely at one point.

And through it all, it has kept paying interest — albeit with some big gaps here and there (the last time the NYSE collected interest was in 2004).

The repairs that it financed are also still there, even though they are somewhat obscured by encroaching nature.

NYSE archivists Peter Asch and David D’Onofrio received the interest on behalf of the Big Board, but promptly donated it to a local dike museum we later visited. We couldn’t resist trying to find out the effective yield of the bond though.

It was obviously gifted to NYSE, but Asch revealed that a few years ago it was for insurance purposes valued at $35,000. So that means a tidy 4.1 basis points a year. KER-CHING.